Doctor Who: “Mummy On The Orient Express”

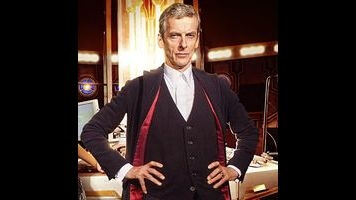

When the time comes to write the final accounting of the 12th Doctor—and hopefully we won’t need to do that for a little while yet—“Mummy On The Orient Express” will loom large. This episode is a triumph for Peter Capaldi, allowing him to turn in his most Doctor-ish performance while continuing to explore and deconstruct just what that nebulous term even means. The Doctor takes casual command of investigating a mystery he knew, or at least really hoped, he was walking into. He knows immediately how he can use the train’s various crewmembers and passengers against the mummy and against the unseen Gus, sizing up Perkins the engineer as a worthwhile ally, Captain Quell as someone he must prod and cajole toward doing anything useful, and Professor Morehouse as little more than a source of information, even in his dying moments. He accepts his role as a researcher in Gus’ grossly immoral experiment, only stepping out of his role as curious scientist and into his more familiar role as crusading hero when he feels he has a decent shot of defeating his adversaries. But even then, as he admits to Clara later in a moment of rare, unvarnished honesty, that sacrifice on Maisie’s behalf was just as cold and calculated as his clinical observation of Quell and Morehouse’s deaths.

In discussing the casting process for the 12th Doctor, showrunner Steven Moffat has said that the screen test for Peter Capaldi involved giving the actor the most impossible monologues, full of ludicrous exposition and constant hairpin emotional turns, because that’s what being the Doctor entails. And that describes the vast majority of the Doctor’s lines in “Mummy On The Orient Express,” with no finer example than the climactic sequence in which the Doctor works out the Foretold’s true nature while also processing Maisie’s emotional damage. That monologue, like so much of the rest of the Doctor’s material in this episode, underlines how words are his greatest advantage. With the Doctor, words are a weapon more deadly than any gun, and they are a tool more powerful than even the sonic screwdriver. In recent years, the Doctor has admitted on more than one occasion that he doesn’t actually know what his plan is until he finishes talking, and Capaldi nails that sense of total unpredictability, of the surprise that comes with every new discovery about the mummy’s identity and about the mistreatment Maisie suffered at her grandmother’s hands. Indeed, he only gets involved because he lays awake in his bed debating the precise percentage of his confidence that everything is fine; it’s just one of a few moments in the episode where the Doctor’s penchant for talking to himself effectively makes him his own companion.

There’s really just one rhetorical technique the Doctor never employs in this episode: He has no interest in comfort or sentiment. In this respect, he once again departs sharply from his immediate predecessors, who had their moments of brutal honesty—remember the 11th Doctor’s matter-of-fact prognosis of Amy’s precarious state in “Flesh And Stone”—but often rallied their latest batch of allies with rousing appeals to be the best of humanity, or whatever alien equivalent thereof. Now, such idealistic statements weren’t exactly insincere, but they could ring hollow as the bodies invariably piled up. Besides, the Doctor’s past efforts to cast himself as the hero left unacknowledged the deeper roots of his actions. As the Doctor says to Clara on the beach, his only real goal was to beat Gus, even if that meant accepting his adversary’s ghastly terms as a prerequisite for taking him on. There’s a kind of grim utilitarianism to the Doctor’s actions here, as his every move—give or take his overlong phone call and the resultant depressurization of the kitchen—is calculated to keep alive the maximum number of people.

What makes this episode such a brilliant progression of ideas explored throughout this season, most notably in “Into The Dalek” and “Kill The Moon,” is that writer Jamie Mathieson concocts a scenario in which the only way for the Doctor to achieve that ultimate, basically benevolent aim is if people die and, in doing so, generate vital data. Doctor Who has long relied on threat-establishing deaths and narratively convenient sacrifices to make its stories work; this episode examines whether such losses are a bug or a feature of the Doctor’s approach by placing him in a situation where those deaths are genuinely inevitable and unpreventable. That conversation on the beach helps us work out the Doctor’s thinking, and it all more or less comes down to a risk calculation, an attempt to achieve some acceptable level of certainty before making the next dangerous move. The cook and the guard die because the Doctor isn’t yet sure what is really going on here—though his interrogation of Professor Morehouse indicates he has a pretty shrewd idea that this is all an elaborate trap—while Morehouse and Captain Quell die because the Doctor hasn’t yet obtained the information he needs to make the Foretold go after him.

Indeed, the Doctor so often mitigates his more callous actions by his willingness to place himself in harm’s way—even if plenty of innocent people have perished while past Doctors have worked out the correct way to place themselves in harm’s way so it’s another clever touch that this episode forces him to remain on the sidelines. To the Doctor’s credit, he does enter the action just as soon as he’s able. But all this allows “Mummy On The Orient Express” to reveal the fundamentally alien nature of the Doctor’s perspective in a way that very few earlier stories have managed. With Clara largely busy elsewhere, Frank Skinner’s Perkins emerges as the voice of human empathy, and the Doctor’s response to the engineer’s call for some basic respect is telling: “People with guns to their heads cannot mourn.” The Doctor is absolutely right, and it helps explain why he doesn’t waste precious time comforting the doomed Quell or Moorhouse, but that’s the kind of detachment that most humans are not capable of, that most humans would not want to be capable of.

If you’ll allow me a moment’s classic Who indulgence, this season in general and this episode in particular feel like what the 80s production team were trying to do with Colin Baker’s 6th Doctor but did not have the skill or the vision to pull off; as this episode lays plain, the Doctor does not have to perform the role of the hero to still fulfill its requirements. And that doesn’t change the fact that it does make it easier for Clara—not to mention the audience—to believe the Doctor is only pretending to be heartless, when the better answer is that just about everything he does is some kind of pretense at this point. As Perkins observes in the final scene when he declines the Doctor’s offer to join him aboard the TARDIS—and given how hardcore a Doctor Who fan Frank Skinner is in real life, I can only imagine how much it killed him to have to deliver those lines—this kind of life could change a person, to which the Doctor replies that it has, several times over. Indeed, the very nature of regeneration, in which each new incarnation is a reaction to the man who came before, means it’s damn difficult for the Doctor to hang onto any kind of fundamental identity; this Doctor is a consciously minimalist incarnation, in which he attempts to strip away 11 (or is it 12, or 13?) lives worth of affectation to get back to the who he really is underneath it all. The only mystery is whether anything actually remains after so much has been stripped away. The burning curiosity is still there, and maybe the goodness is too. But it’s a colder goodness, experienced more through the prism of an aloof, cosmically-minded Time Lord aristocrat than of the more visceral, compassionate example set by his human companions.

So then, let’s talk about the human companion. After “Kill The Moon,” quite a few people—myself included—speculated that the next episode would find the Doctor traveling without Clara, given her stinging rebuke of him and his treatment of her at the end of that episode. The BBC even tweaked the episode description for “Mummy On The Orient Express” to remove Clara’s name, playing up just that possibility. As such, it’s actually almost disappointing to see both Clara and the Doctor step out of the TARDIS at the beginning of the episode, as though we’ve skipped past the vital next step in this story. But, as the episode soon makes clear, this is not a Doctor who would have spent his time away from Clara deeply considering the errors of his ways. Words are indeed his weapon, but they are also his shield, and he repeatedly deflects any of Clara’s efforts to bring up her feelings in favor of talk of planets. And yes, I realize there are plenty of Doctor Who fans who prefer planets to feelings—hell, I spent a good chunk of the Russell T. Davies era in that category—but “Mummy On The Orient Express” is perceptive in how it teases out the nuances of the Doctor and Clara’s relationship, even if only one of them really wants to talk about it.

That’s not to say the Doctor never considers his companion’s emotions; it’s just that he rarely understands them, as his repeated discomfort at her sad smile handily indicates. He makes some effort to respect her wishes, but my goodness is the word “some” doing ridiculously heavy lifting in that sentence. After all, as he admits just before the climactic confrontation, he’s been ducking Gus’ attempts to bring him on board the train for centuries, and he only came here because he hoped something exciting would happen. Whether that counts as lying to her—it totally does—is almost beside the point, as it all just goes back to the fact that, no matter how often he regenerates, the Doctor is never going to change. The contours of his eccentricity and his remove from humanity might morph slightly from incarnation to incarnation, but the Doctor is perhaps at his most truthful when Clara asks him why the end of their journeys together must mean the end of their friendship. Give or take his predecessor’s emotional dependence on the Ponds, the Doctor just isn’t the kind of person who drops in on old friends for dinner, not unless the universe is about to explode.

That’s why the whole concept of the last hurrah feels so new for Doctor Who. The Doctor has always been someone who prefers to let goodbyes hit him like a ton of bricks and then just keep moving; the idea of a gradual, preplanned farewell has precious little precedent in the show’s history. The previous era attempted something sort of like this with Amy and Rory’s slow-motion departure, one that began in “The God Complex,” was recapitulated in “The Power Of Three,” and then turned into something totally different and more in line with consciously heartbreaking Davies-era exits in “The Angels Take Manhattan.” And yes, the end of “Mummy On The Orient Express” is superficially similar to that of “The Power Of Three,” as both stories end with companions rejoining the Doctor after a prolonged crisis of conscience about whether that’s really the right course of action. The difference is that “The Power Of Three” treated Amy and Rory’s decision as a more or less positive thing, even if it’s hard to ignore that “The Angels Take Manhattan” lay directly ahead; I mean, Brian Williams gave the decision his blessing, and I know better than to disagree with Brian Williams. Tonight’s episode, by contrast, places Clara’s sudden change of heart in a far less encouraging frame.

So much of telling a successful Doctor Who story—or, perhaps more precisely, an accessible one—lies in locating the right metaphor to translate the show’s more rarefied elements. Doctor Who may well be a great spirit of adventure, but that doesn’t mean its premise is particularly relatable; very few of us have traveled through time and space in a big blue box with a 2,000-year-old alien, and those that have are keeping damn quiet about it. I’d argue one of the many reasons the latter portion of the 11th Doctor era is so divisive is that it basically abandons metaphor and analogy in favor of a more direct exploration of what it means to be the Doctor and to travel with him, so it’s not exactly surprising that those stories leave so many fans cold. More recently, so much of the criticism of “Kill The Moon” has focused on the imprecision of its metaphors, to the point that there remains fierce debate as to what the metaphor even is. Well, “Mummy On The Orient Express” leaves no doubt what its metaphor of choice is for the Doctor and Clara’s actions. The Doctor may or may not be addicted to making the impossible decisions, but Clara is definitely addicted to traveling through time and space.

As with “Kill The Moon,” “Mummy On The Orient Express” surprises me in just how well—and, yes, how vitally—the episode uses Clara. She doesn’t spend much time with the Doctor; indeed, I might guess that, rather like how “The Girl Who Waited” kept Matt Smith inside the TARDIS for almost all the running time so that he would be free to shoot “Closing Time” simultaneously, it’s possible Jenna Coleman’s shooting schedule was condensed for this episode so that she could work on next week’s entry. But such speculation is really beside the point, for though Clara spends much of the Orient Express section on the periphery, her eventual role does boil down everything that is both wondrous and terrifying about the Doctor. After all, after spending most of the episode locked in a closet with Maisie and a sarcophagus, it’s Clara’s grim duty to deliver the former to her apparent death; we can only assume the Doctor succeeded in fooling Gus about his true intentions, but there’s no doubt at all that the Doctor has once again betrayed Clara’s trust. She doesn’t summon forth the same rage that animated her big speech in “Kill The Moon.” Instead, she still brings Maisie to the Doctor’s car, and her anger at being used only lasts so long before giving way to resignation. This simply is what travel with the Doctor entails, and she wants no part of it. As Danny Pink suggested last week, Clara won’t be through with the Doctor for as long as he can still make her angry. We’re not quite there yet, but “Mummy On The Orient Express” gets us much, much closer to that point that “Kill The Moon.”

And yet, Clara stays. This is where we come back to the addiction metaphor. Broadly speaking, I think this is a good analogy for the show to try on and explore. Throughout all the wildly different TARDIS combinations we have seen throughout the new series, the one constant has been the notion that this centuries-, even millennia-old alien can offer ordinary little humans all of time and space, and all he seemingly wants in return is their friendship—their companionship, if that’s not too old-fashioned (or too loaded with salacious connotations) to use here. But the intensity of such a relationship, of such a lifestyle means new Doctor Who has never been comfortable depicting it as just a couple of pals knocking about the cosmos.

For Rose and Martha, the chosen metaphor was a romantic relationship, or the failure of same. Donna insisted that she and the Doctor were strictly friends—so of course the entire universe, Roman Peter Capaldi included, assumed they were husband and wife—but her insistence to Martha at the end of “The Doctor’s Daughter” that she would stay with the Doctor forever suggested its own kind of loss of perspective. Yes, traveling in the TARDIS is incredible, and unlike anything one might find on Earth, but it’s still dangerous to so completely untether yourself from human life; in Donna’s case, the fact that she didn’t really have a life back on Earth made it all the more essential she invest everything in her travels with the TARDIS, and all the more cruel and heartbreaking when that was all ripped away from her. And then Amy and Rory eventually became friends, even family—well, the in-laws, technically—but the show could never resist playing up the love triangle aspect, albeit not always entirely seriously.

“Mummy On The Orient Express” has a few points in which characters try to fit the Doctor and Clara into that old relationship analogy. Maisie becomes approximately the 20,000th person on new Doctor Who to ask whether the Doctor and Clara are a couple, while Clara herself has to be corrected when she asks Danny if she should go ahead and “dump” the Doctor. It’s as though the show itself is acknowledging how completely that analogy has suffused our conception of the show; whatever narrative good the love metaphor has done for the show in the past, it feels inappropriate here. That’s because the idea that the companion travels with the Doctor because she loves him feels like it misses the point. Yes, the Doctor is a mysterious, charming, alluring figure, but he’s just the designated driver. It’s all of time and space—“Now shut up and show me a planet!” as Clara commands at the end—and, yes, that great spirit of adventure that is really at the core of Doctor Who’s appeal. Given the choice of walking away from that for good, Clara finds that her deeply mixed feelings for the Doctor are not enough to offset her love of that adventure.

In that view, this episode and its predecessor have very pleasantly surprised me, as I might well have spoken prematurely in my review of “The Caretaker” when I said Clara would never be a vital character. As soon as she pulls that lever on the TARDIS console—hell, as soon as she decides to lie about Danny as cover for changing her own mind—she is setting herself upon a doomed course. Clara is the companion with the strength of character to even consider walking away; the fact that she can’t ultimately go through with it is only moderately a failure on her part, and even there it’s more about the less than honest way she handles it than anything else. And when it comes to concealing the truth, let’s not forget that Clara learned from the master. Appropriately for an episode in which we actually see those 66 seconds tick away, it’s as though the great countdown clock has started, and both the Doctor and Clara are headed for a reckoning as a result of their tendency to choose what they want to hear over what they know in their hearts to be true. Even this most alien Doctor probably knows that Clara is, well—relapsing is too strong a word—and should not necessarily be allowed to keep traveling with him under those circumstances. But look at the expression on his face. The Doctor is overjoyed to have Clara back in a way he so rarely is in this incarnation. Let’s allow them both this moment’s happiness, even if there’s just no way this can possibly last.

“Mummy On The Orient Express” is the latest superb episode in a strong season. Peter Capaldi’s performance is enough by itself to elevate this story to classic status, but Jamie Mathieson’s script provides him excellent support, offering fascinating ideas and incisive progression of the ideas that have been developed throughout this year. Throw in the glorious silliness of combining the early 20th century opulence of the Orient Express with the cosmic vistas of space, and the episode is the year’s best demonstration of the kind of ridiculous stories that can really only be told on Doctor Who. Over the past few weeks, the show has begun to smash its way out of the formula that came to define and occasionally restrict it since the show’s return. I officially have no idea what’s coming next, and that’s a wonderful feeling.

Stray observations:

- There are some lovely callbacks and continuity references in this episode. Capaldi becomes the latest Doctor to ask a monster whether it’s his mummy, and he acknowledges that Gus was the person on the other end of the phone call at the conclusion of “The Big Bang.” But the best one by far is the revelation of what the Doctor keeps in his cigarette case: jelly babies. Welcome back, old friends.

- In a season already full of fine supporting performances, “Mummy On The Orient Express” has several great guest stars. Frank Skinner does an admirable job of playing Perkins as essentially the Doctor’s fill-in companion, working well as both the Doctor’s sounding board and his occasional intellectual equal. Daisy Beaumont plays Maisie with just the right amount of vulnerability, keeping the character from moving into complete caricature territory. And John Sessions is just the right combination of ominous and obsequious as the voice of Gus.