Doctor Who: “Robot Of Sherwood”

For most of its running time, “Robot Of Sherwood” feels oddly untethered, as though the episode is never sure what point it wants to make. Without a clear central thesis to propel the episode, its disparate elements never quite cohere. The Doctor’s obstinate refusal to consider the possibility that Robin Hood is real suggests that the audience should turn its attention to the robots and attempt to puzzle out their plan. If Robin Hood is a robot, as the Doctor insists, then are the Merry Men as well? And what about the Sheriff of Nottingham? Is all this some cockamamie scheme by the robots, or did they just happen to wander into a historical setting that more or less exactly matches all the legeneds of Robin Hood? By throwing its own reality into question, “Robot Of Sherwood” leaves its audience adrift, particularly when it then proceeds to ignore the issue for significant portions of the story. It’s only in the final five minutes that the episode attains some clarity, as Robin Hood and the Doctor have their final conversation, speaking to each other not so much as two men of flesh and blood but as two of Britain’s most legendary culture heroes having their long overdue meeting.

As Robin observes, “And remember, Doctor, I’m just as real as you are,” and that’s the key takeaway. In the real world, there’s absolutely a place for skepticism when it comes to Robin Hood, who might have some basis in historical fact, but more likely doesn’t; at the very least, any historical Robin Hood would likely be so far removed from the legend so as to be virtually unrecognizable. But “Robot Of Sherwood” isn’t set in the real world. It takes place in the world of Doctor Who, and if there’s one fictional universe that is British enough, silly enough, and, yes, old-fashioned enough in its sense of heroism and virtue to incorporate the Robin Hood of legend, then it must surely be Doctor Who. To deny the possibility of Robin Hood is to deny the possibility of the Doctor, so what does it say that the Doctor is so hell-bent on debunking Robin Hood’s very existence? Mark Gatiss’ script struggles to locate the precise reason why the Doctor has such an issue with this Robin Hood, leaving a bit too much room for wild speculation (always a risk in Doctor Who, admittedly). For instance, if I squint, I could see the dashing, jocular Robin Hood as a stand-in for the 11th Doctor, or at least for how the current incarnation views his predecessor, a possibility vaguely supported by Clara’s question about when the Doctor stopped believing in everything.

But “Robot Of Sherwood” isn’t really trying to make any so specific a point. Broadly speaking, this episode does provide a more lighthearted spin on this season’s ongoing question about whether the Doctor is still a good man in this new, minimalist form. This new Doctor may be uncomfortable in the role of hero, but that doesn’t make him any less of one. Again, there’s a clarity of vision in that final scene between Robin and the Doctor that just shockingly outstrips everything that precedes it: “If we both keep pretending to be—ha, ha!—perhaps others will be heroes in our name. Perhaps we will both be stories. And may those stories never end.” Leaving aside all the metatextual business about the enduring value of storytelling and heroic fiction as modern mythology—for which I’m a complete sucker, but I realize is awfully abstract for most viewers—the crucial point there is that we can judge people like the Doctor and Robin, both of whom exist more as myths than as men, by what they inspire in others rather than by what they do themselves. And, in both cases, we need only look at Clara.

The great Clara Oswald Reclamation Project of 2014 continues apace, as for the third straight episode the companion is given plenty of good material. That’s not necessarily surprising, given that Mark Gatiss wrote one of last season’s strongest Clara entries in “Cold War,” but it’s heartening to see just how carefully this story positions Clara’s faith in Robin Hood and the Doctor. Last year, Clara’s trust in the 11th Doctor—a largely unearned trust, given how much he was concealing from her—could take on the form of a kind of hero worship, in which her expressions of faith existed only to buoy the Doctor into action in moments of crisis. The show wrung a few powerful moments out of that dynamic, most notably the climax of “The Day Of The Doctor,” but this approach didn’t help the general sense of Clara as a cipher.

Here, however, Clara absolutely geeks out when confronted with Robin Hood, and she absolutely affirms her belief that the Doctor is a hero, but she doesn’t waste time waiting for them to stop acting like idiots. Really, this is what Robin is talking about in the final scene: The idea of the Doctor and Robin Hood is more than enough to inspire Clara to be the hero, even when the only reason she has to be the hero at all is because the actual men behind the legends are squabbling like children. Indeed, on that point, this episode doesn’t make any specific references to Clara being a teacher, but the mere fact that “Deep Breath” and “Into The Dalek” so strongly established her profession as part of her character adds extra resonance to any scene where she must lecture the two recalcitrant heroes. We’ve heard a lot about Clara being “bossy” or “a control freak,” both of which have always struck me as bizarrely negative ways to describe what could be better termed a “take-charge attitude.” The dungeon scene is the perfect distillation of what I think the show is getting at when it calls Clara bossy; the fact that that word is never used to describe her actions suggests Doctor Who has now recognized that Clara’s occasional exasperation with the Doctor’s flightiness is an asset, not a weakness.

Beyond being a legitimately funny scene in an episode that all too frequently strains for comedy—Peter Capaldi absolutely nails the Doctor’s smug delight when he asks Clara to confirm that it would take him longer to starve to death—the dungeon sequence typifies how Clara is used in this episode. When faced with a hopeless situation, she doesn’t waste precious time on inspiring monologues meant to convince Robin and the Doctor that it’s time for them to save the day; instead, Clara assesses whether either of these theoretical heroes could help her get out of here, and she fast concludes that she’s going to have to take care of herself. As her dinner with the Sheriff of Nottingham demonstrates, she’s entirely capable of doing just that. It’s a nicely balanced scene, perfectly played by Jenna Coleman, as Clara flatters information out of the vain ‘sheriff without having to overplay the uncomfortable role of seductress; she never really drops her Blackpool-bred obstinacy, instead telling the Sheriff the bare minimum he needs to hear and letting his ego do the rest, all while keeping as much distance as she can from the odious cur. Whenever “Robot Of Sherwood” works, Clara is usually involved: Whoever thought I’d be writing that this time last year?

As for the Doctor, the episode is more of a mixed bag. Peter Capaldi is a gifted comedic actor, but he can’t land some of the episode’s goofier material. This is almost certainly reductive, but the basic rule of thumb here is that Capaldi does best with the jokes that most resemble things Malcolm Tucker would say, while he struggles with the more whimsical lines that would likely make more sense coming out of Matt Smith’s mouth; in particular, the Doctor’s rant against banter sounds a little too much like something his predecessor would say. If you’re looking for a quintessential 12th Doctor comedic exchange, look no further than the opening scene, in which he asks whether people ever punch Robin Hood in the face after one of his laughs, then caustically observes, “Lucky I’m here, then.” However, the subsequent swordfight—or spoonfight, depending on one’s perspective—veers dangerously close to self-parody. In theory, Capaldi’s harder edge could cut against the inherent whimsy of the scene, but it doesn’t quite work here; this plays like the kind of scene that the show could perhaps pull off later in a Doctor’s run, when writers and actor have a finer-grained understanding of the character, but here it just misfires. Still, even if the big goofy setpieces don’t show this new Doctor at his best, Capaldi does reliably excellent work in the smaller moments; the Doctor feels alien in a way he hasn’t in quite some time when he bites into an apple while analyzing it with his sonic screwdriver, or when he reacts in shock to the grateful Marian’s kiss.

“Robot Of Sherwood” is frequently farce, and that’s where the prolonged uncertainty about Robin Hood’s true nature becomes so troublesome. The episode’s ostensible mystery invites the audience to not take the characters seriously, when farce, in its way, has to be taken far more seriously than drama. After all, in the latter, you presumably have real, grounded emotions and character dynamics to work with, and those allow the viewers to remain engaged while the story sorts out what is and is not actually going on. But how is the audience supposed to react, say, to the archery contest? Is the goofiness of the sequence, including the fact that Robin Hood apparently believes nobody can recognize him in his paper-thin disguise, meant to be straightforward comedy, or is the audience supposed to interpret it as proof that this entire scenario is too silly for words, and thus proof that this is all a big sham? Comedy, no matter how anarchic its form, needs rules and structure in order to work; otherwise the audience tends not to think it has permission to laugh. “Robot Of Sherwood” attempts to tell three or four different potential stories—one in which Robin Hood is real, another in which he’s a robot, another in which everyone is a robot, and so on—when it would be more effective collapsing itself into one clear, coherent storyline.

What makes the medieval material work at all is the supporting cast, which is basically just two men: Da Vinci’s Demons star Tom Riley as Robin Hood and comedian Ben Miller as the Sheriff of Nottingham. Miller, sporting a beard and an acting style that can really only be described as Anthony Ainley-esque, chews just the right amount of scenery as the Sheriff. The character is portrayed as unrepentantly evil and more than a little insane, but Miller conveys an internal logic to that madness that keeps him out of pantomime territory. He’s a “pudding-headed primitive,” as the Doctor so eloquently puts it, but he can also be a particularly revolting kind of suave. Riley is similarly good as Robin Hood, taking the initial caricature of a uncomplicated heroism and gradually deepening his performance, adding in pathos and childishness in equal measure. Robin Hood turns into a real person just as the story requires, and it’s Riley who carries that fantastic final scene with Robin and the Doctor. Besides, Riley and Miller both have enormous fun with the climactic swordfight, going fearlessly over the top in a way that might well have served the rest of the episode well.

At worst, “Robot Of Sherwood” is an inoffensive lark, a lighthearted diversion in the midst of some seriously dark episodes (I mean, did you see the trailer for “Listen”?). Mark Gatiss’ script gets enough right on the edges—in particular, I love how much intelligence and perceptiveness all the 12th century characters show, from Robin’s calm reaction to the TARDIS to Alan-a-Dale’s speculation on the gold to Marian’s quick understanding of the Doctor’s plan—to offset, at least partially, the episode’s underdeveloped core, and those more successful peripheral elements make the episode more enjoyable on a rewatch. And, again, that final conversation really is something special, touching on why Robin Hood and Doctor Who have carved out such important niches in their cultural lexicon. This episode disappoints not because it’s an unmitigated disaster, but because it could so easily have been something really special.

Stray observations:

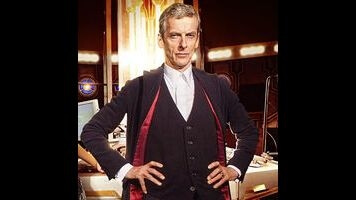

- In what may well be my favorite Easter egg in Doctor Who’s 50-year history, the computer databanks on Robin Hood include this image of the title character from 1953’s Robin Hood, the very first televised adaptation of the Robin Hood story. As classic Doctor Who fans might well be able to tell, the man who played TV’s very first Robin Hood was none other than Patrick Troughton, the 2nd Doctor, and so his inclusion here is about eight different flavors of wonderful.

- This season, I’ve tried to downplay the discussion of classic Doctor Who in my reviews, as I think their inclusion in last year’s reviews did sometimes leave newer fans out in the cold. Still, given all the comparisons between the 3rd and 12th Doctors when the latter’s costume was introduced, I think it’s fair to say that Capaldi cuts a rather dashing, Jon Pertwee-like figure at points in this episode. I’d be shocked if “Robot Of Sherwood” doesn’t aspire to be a 21st century answer to the 3rd Doctor classic “The Time Warrior,” which also features a smalltime medieval thug getting ideas above his station with the help of alien technology. That said, I’d say the closer parallel is with the rather less well-regarded 5th Doctor story “The King’s Demons”—from which the linked Anthony Ainley clip is taken—as both that and this story struggle to figure out just how seriously they should take the 12th century setting. Anyway, the point is that I recommend everyone go off and watch “The Time Warrior,” because it’s pretty damn terrific.

- Also, if I’m doing cross-era comparisons, it’s interesting to think of “Robot Of Sherwood” as a latter-day take on the celebrity historical, a storytelling form that was a fixture of the Russell T. Davies era but has pretty much dropped away under Steven Moffat’s tenure. Apart from “Tooth And Claw,” which I dislike for reasons that I’ll admit aren’t entirely rational, there’s plenty to like in all of those entries—Mark Gatiss’ own “The Unquiet Dead” is particularly strong—but Steven Moffat and Richard Curtis did kind of blow up the subgenre with the beautiful “Vincent And The Doctor,” which rather spectacularly cut against the historical hero worship that bogged down the Davies-era episodes. Either way, give or take the slightly different roles played by Richard Nixon in “The Impossible Astronaut”/“Day Of The Moon,” Queen Nefertiti in “Dinosaurs On A Spaceship,” and Queen Elizabeth I in “The Day Of The Doctor”—and, uh, Hitler in “Let’s Kill Hitler”—Robin Hood is the first major (semi-)historical figure to be featured on the show since Vincent Van Gogh, and that was over four years ago. And, if nothing else, I’ll give credit to “Robot Of Sherwood” for finding another twist on the celebrity historical format, namely to have the Doctor and Robin Hood spending most of the episode hating each other’s guts.