Doctor Who: “The Empty Child”/“The Doctor Dances”

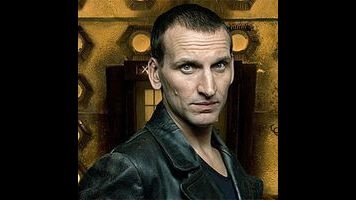

At the risk of a rather basic, nearly decade-old spoiler, it’s difficult to approach Christopher Eccleston’s season as the Doctor without the knowledge that it’s his only season in the role. Then again, it’s not as though that puts us in a different position than viewers back in 2005. Eccleston’s departure was privately decided upon back in January 2005, three months before the show even aired. His exit was later officially announced in an infamous BBC press release that falsely claimed he had left the roles for fear of being typecast, a rumor that endures to this day. That announcement came on March 30, just five days after the premiere of “Rose.” On April 16, the day that “Aliens Of London” aired, David Tennant was announced as the next Doctor. In a sense, Eccleston was the incumbent Doctor for less than a week; by the time “The End Of The World” aired, he was no longer simply the Doctor but rather “the current Doctor,” the man marking time until his replacement inevitably showed up at the end of the season.

What that means is that, with the slight exception of “Rose,” the 9th Doctor’s tenure was never open-ended, which ended up emphasizing this incarnation’s character arc that plays out over the course of 13 episodes. Eccleston and Russell T. Davies make the most of the limited time they have in which to explore this Doctor, and it’s possible to see each story as restoring a vital piece of this shattered incarnation. “Rose” sees him reengage with humanity by finding a new companion, “The End Of The World” brings his Time War trauma to the surface, “Aliens Of London” and “World War Three” has him acknowledge the terrible responsibilities that come with saving worlds, “Dalek” has him confront his worst nightmare and decide whether he still wants to be better than it. There are a few exceptions here, but those mostly serve as character pieces for others—“Father’s Day” for Rose and “The Unquiet Dead” for Charles Dickens, of all people. Just about every episode specifically featuring the 9th Doctor feels important, as though it’s trying to make a profound statement about just who this man with the leather jacket and the superpowered nose really is.

I realize that it sounds like I’m setting this up as some sort of criticism, but don’t worry: That would be insane. In part because his story was almost always conceived as a finite arc, the 9th Doctor still has the clearest, most detailed character progression of any incarnation, and I doubt that achievement will be surpassed anytime soon. The reason I bring this all up is because there are precious few moments throughout this season in which it feels like the Doctor is just getting on with the business of being the Doctor and having adventures. In terms of the larger context of this first season, that makes sense, for these 13 episodes essentially served as a proof of concept for the entire notion of a revived Doctor Who. Russell T. Davies had to prove that this show could still work after 16 years of hibernation, and so he could take nothing for granted in gradually reintroducing the show’s most iconic aspects—not only elements of the mythos like the TARDIS and the Daleks but also key storytelling elements like the companion, the alien invasion, and time travel to the past and the future.

“The Empty Child” in particular feels like something different from all of that. It’s an episode-long expansion of the sort of investigating that the Doctor briefly got up back in “Aliens Of London,” when he briefly left Rose behind and went to check on the alien in the spaceship crash. It’s not that the Doctor can’t be himself with Rose around, but we’re still very much at a point where Rose is arguably the true protagonist of the show; look at how much the season’s other classic entries, “Dalek” and “Father’s Day,” ultimately revolve around her as the emotional crux, with the Doctor positioned as the more removed, alien presence. The 9th Doctor gets to dominate the screen in “The Empty Child” in a way that he doesn’t always get to do elsewhere, and it’s likely not a surprise that his emotional range feels more human and accessible than it has done previously. His godlike, self-righteous anger only emerges briefly, and it’s hard to argue with his harsh words to Captain Jack for his near-genocidal carelessness. Elsewhere though, the Doctor gets to be witty, determined, goofy, reflective, uneasy, and ultimately ecstatic; Eccleston carries off every emotion that Steven Moffat’s script asks him to play, with the possible exception of goofiness. But that’s fair enough, really.

The cumulative effect is an episode that comes closer to any other to feeling like the continuing adventures of the 9th Doctor, rather than an entry in a self-contained, inherently limited arc leading to his inevitable departure. Even then, the second half of the story, “The Doctor Dances,” delves deeply into the Doctor’s character once again, but its treatment of this subject feels different from what the show was trying to accomplish in, say, “Dalek.” In that earlier story, the Doctor’s most deeply held beliefs were challenged, first by Rose and then by the Dalek itself. The show was still in the process of defining just who the Doctor was, and he had to prove himself to Rose and, by extension, the audience. As Rose observes here, “The world doesn’t end because the Doctor dances,” but the opposite is true, too; the episode’s euphemistic discussion of the Doctor’s sexuality is important to understanding the character, but it doesn’t threaten to undo him in the same way that blasting that Dalek in cold blood would have. It’s likely not a coincidence that this story features only a couple passing, oblique references to the Time War, where almost every previous episode had some extended, explicit acknowledgment of the trauma the Doctor was working through.

But then, that’s the real genius of “The Empty Child” and “The Doctor Dances.” Where before the Doctor could only process his post-war trauma through sadness and rage, the resolution of this story allows him a rare measure of pure, unqualified joy. When the Doctor rhapsodically announces that everybody lives, he is, in some small way, making up for every single death that has ever weighed down his conscience. It really is close to unprecedented for the Doctor to save literally everybody, and no incarnation ever needed such a complete triumph like this one does. I’ll get into this more in next week’s review of the finale, but so many of the Doctor’s stories this season seem to subscribe to the notion that the 9th Doctor was something of a regenerative incarnation, a Doctor who existed solely to rebuild himself in the aftermath of the Time War, which fits in neatly for this first season’s attempt to rebuild Doctor Who as a show. Once that task of reconstituting himself was complete, this Doctor’s task would be done, and the only way to truly release the worst of his grief and his rage would be to take it with him, to let some new man have a fresh, happier start.

That’s a big reason why it’s so hard to imagine Christopher Eccleston playing the 9th Doctor for a second season, but this story does offer the clearest indication that this Doctor didn’t absolutely have to leave, that he could have truly rediscovered the joy of being the Doctor if he had stuck around long enough. As it stands, “The Empty Child” and “The Doctor Dances” represent the 9th Doctor’s ultimate triumph, both as his greatest in-universe accomplishment and as his best story, and part of why it remains so exhilarating to watch is the sense that neither the Doctor nor the show is trying to prove anything. The audience has had eight episodes to get to know this new Doctor Who, and now it’s time the show reveals what it’s truly capable of. You want to see moves? Doctor Who will show you moves.

“The Empty Child” (season 1, episode 9; originally aired 5/21/2005)

(Available on Hulu, Netflix, and Amazon Instant Video.)

“Mommy? Are you my mommy?”

Here’s one way to understand just how old Doctor Who is: The show’s first episode, “An Unearthly Child,” aired on November 23, 1963. “The Empty Child” would air 42 years later, but the Second World War had only ended 18 years earlier. Indeed, Doctor Who’s handling ofWorld War II ably demonstrates how the show has evolved in the public consciousness over its half-century of existence. It would have been unthinkable for any of the early Doctors to land the TARDIS in the middle of the Blitz, and it was controversial enough when “The War Games,” Patrick Troughton’s 1969 swansong as the 2nd Doctor, appeared to land the Doctor in the midst of a First World War battlefield. The horrors of World War II could only be broached allegorically; most famously, Terry Nation explicitly based the Daleks on the Nazis, a fact that was at its most obvious in the Tom Baker serial “Genesis Of The Daleks,” in which one of the proto-Dalek bad guys actually wears an Iron Cross. By the final season of the classic series, enough time had passed that Doctor Who could make something like “The Curse Of The Fenric,” which was set during World War II but took place far from the Blitz, let alone the front line.

“The Empty Child” and “The Doctor Dances” derive so much of their power from their wartime setting. For all its constant financial struggles—even at its most expensive, Doctor Who is made on a fraction of the budget of its American counterparts—the BBC has always been good at replicating the past on a budget. The fact that the entire story takes place over a single night helps, as director James Hawes skillfully uses the darkness to hide what appears to be a fairly limited set of locations. The two-parter greatly benefits from the audience’s familiarity with previous wartime stories; even minor characters like the corrupt, uncouth Arthur Lloyd and the valiant, stiff-upper-lipped Algy have some extra dimensions they might not otherwise have simply because they fit into existing archetypes of characters that one expects to encounter during the Blitz. Steven Moffat’s script barely needs to bother establishing who the audience expects these characters to be before it sets about subverting expectations, as with the revelation that Mr. Lloyd—the sort of overbearing boor likely obsessed with presenting him as a pillar of the local community—enjoys black market meat because of his illicit affair with the local butcher, Mr. Haverstock.

This is the show’s third trip to the past, following on from “The Unquiet Dead” and “Father’s Day,” and the World War II setting sits in just the right position between the mundane proximity of 1987 and the almost alien remove of 1869. World War II is a time period still within living memory, albeit not for most of the story’s viewers; it’s the kind of event that the audience can feel connected to while still being able to think about it more in terms of its familiar iconography than its grim reality. More than six decades removed from the Blitz, it’s hard for the story of Nancy and her band of orphans to avoid having a storybook quality, something Moffat’s script acknowledges when the Doctor observes that he’s not sure if Nancy’s plan is “Marxism in action or a West End musical.” The mere presence of the Doctor and the TARDIS means that a historical story is never going to be “realistic” in any normal sense of the term, but what this story does capture is a certain authenticity of mindset. The story considers deeply what it means to live in constant, dulled fear of a bombs falling from the sky. The usual round of madness and death associated with the Doctor turning up barely rates when compared to the terror of the Nazi war machine.

Florence Hoath is terrific as Nancy, carefully pitching her character’s steely resourcefulness so that it never feels out of place in the context of her time and place. She has witnessed terrible, impossible things in her short life, and the two-parter smartly recognizes that her experiences with the Chula warship represent only a tiny fraction of the horrors she has seen. As she tells Rose before the final confrontation with the empty people, she has no trouble believing in time travel, but she can’t bring herself to believe in a future where Londoners still speak with English accents. Right up to the climax, the Doctor and Rose are the only ones actually fighting to win the day; Nancy and Dr. Constantine make it clear that the only goal they have left is another day’s survival, even though both appear convinced that they are simply marking time until the inevitable German victory. That helps make the Doctor’s ultimate triumph all the more exhilarating, as he defeats death in a place already so singularly starved of hope. London in 1941 is one of the few places already so suffused with unreality that a woman could regrow her leg and Dr. Constantine could actually, semi-plausibly offer the brilliant response, “Well, there is a war on… is it possible you miscounted?”

Not every element of the wartime setting works, admittedly; the sequence where Rose finds herself hanging in midair during a German air raid overtaxes the special effects budget, to the extent that it’s sometimes a little difficult to understand quite what’s going on or how everything fits together spatially. It also seems to beggar belief that Rose could really hang onto a rope for quite that long, but I suppose this is where that bronze medal-winning skill at under-sevens gymnastics comes in handy. Still, I’m generally willing to grant any given Doctor Who story at least one massively implausible plot point, so long as it’s in the service of stronger storytelling elsewhere. Rose’s sojourn on that rope helps bring her into contact with Captain Jack Harkness—plus her rope burns set up the crucial plot point of the nanogenes—so I’m inclined to be charitable.

It’s worth acknowledging just how baldy patriotic this story is. Doctor Who has always been a proudly British show, but it’s rarely quite so obvious about it; the entire story is the equivalent of, to pick an example entirely at random, wearing a giant Union Jack on one’s T-shirt. The show is directly interacting with one of the most proudly heroic chapters of Britain’s national narrative, and the Doctor offers multiple paeans to the indomitable character of the inhabitants of this damp little island. Such mythologizing ties in neatly with how the show handles the contrast between the Doctor and Captain Jack. John Barrowman’s ex-Time Agent conman takes to its illogical extreme the old description of American soldiers in Britain during World War II: “Overpaid, oversexed, and over here,” assuming we can let “overpaid” stand in for “overly equipped with a truly impressive array of alien tech.”

This story sets up an implicit comparison between shows like Doctor Who and Star Trek, what with the constant references to “Mr. Spock.” There was an even more obvious acknowledgment of this contrast in the original script, in which the Doctor would have responded to the Mr. Spock alias with the response “I’d rather have Doctor Who than Star Trek,” although that line probably would have been a step too far. Either way, this story reaffirms the Doctor as a quintessentially British hero, one who cannot hope to equal the flash of his American counterpart but who makes up for it by actually saving the day. That’s an idealized view, to be sure, but it fits perfectly with a story that is set during Britain’s proverbial finest hour.

Stray Observations:

- Given Steven Moffat’s background as a comedy writer, it’s not really surprising just how witty and absurdly quotable both of these episodes are. As such, I’m turning this week’s stray observations over to a brief collection of a few of my favorite quotes.

- “Oh, and could you switch off your cell-phone? No, seriously, it interferes with my instruments.” “You know, no one ever believes that.”

- “Do your ears have special powers too?” “What are you trying to say?”

- “Oh, should've known, the way you guys are blending in with the local color. I mean, flag girl was bad enough, but U-boat captain?”

- “1941. Right now, not very far from here the German war machine is rolling up the map of Europe. Country after country, falling like Dominoes. Nothing can stop it, nothing until one tiny, damp little island says ‘no.’ No, not here. A mouse in front of a lion. You’re amazing. The lot of you. Don’t know what you do to Hitler, but you frighten the hell out of me. Off you go, then. Do what you got to do. Save the world.

”

“The Doctor Dances” (season 1, episode 10, originally aired 5/28/2005)

(Available on Hulu, Netflix, and Amazon Instant Video.)

“What’s life? Life’s easy. A quirk of matter. Nature’s way of keeping meat fresh.”

Leaving aside the classic series’ three multi-Doctor stories and a handful of now obscure single-episode titles from the William Hartnell era, “The Doctor Dances” is the first episode in the show’s history whose title explicitly refers to its protagonist. It’s an odd title, really; whereas “The Empty Child” is perfectly evocative of the terror that defines the first half of the two-parter, it’s not as though the Doctor’s dancing—euphemism or otherwise—is really what the second episode is all about, at least not on the surface. But perhaps the title simply reflects that, after several episodes in which Rose is the primary focus and the audience identification figure, Doctor Who is ready to make its title character the focus.

Doctor Who is a story where only the tiniest fraction of what happens to its main character actually ends up on the screen. That just comes with the territory of following the exploits of a 900-year-old alien. As such, the show throughout its history has excelled at alluding to unseen adventures; it’s part of why the Doctor has always been such an inveterate namedropper. A small piece of this two-parter’s brilliance, then, is in how it invites the viewer to imagine several other stories for the Doctor. There’s the weapons factory at Villengard, which the Doctor visited once but has been replaced with a banana grove after the reactor went critical—like the Doctor said, he visited it once. In a handful of lines, the Doctor relates another complete Doctor Who story, one that can be imagined in at least nine different ways based solely on which incarnation the viewer believes actually did the deed. That exchange with Jack also functions as a character moment for both parties. Confronted with a dashing, well-prepared freelancer—as Rose puts it, “finally, a professional”—the Doctor self-consciously reasserts his position as the all-powerful idealist, someone who is willing to take the most extreme actions in the name of confronting evil. If that means blowing up the occasional factory or shop, well, that’s just how the Doctor communicates. It’s not really the most flattering way for the Doctor to present himself, but he knows enough to realize he can’t hope to compete with Jack on the fraudulent Captain’s terms.

The story also hints at stories for the Doctor that are more personal than any the audience has previously witnessed. One of Eccleston’s many moments of quiet brilliance as the Doctor comes when he sympathizes with the child left out in the cold, affirming that he knows all too well what it’s like to be in that position. The Doctor’s childhood is a subject barely ever broached in any era of the show; that solitary line probably represents one of the five biggest revelations about the Doctor’s younger days, and I suppose it’s still theoretically possible that he isn’t really talking about an actual childhood at all. It’s a throwaway line, really, but it serves as a worthwhile reminder that the Doctor didn’t pop up fully formed as the universe’s ultimate hero, that he too can have his own personal pain and sadness that reaches back deeper than the tragedies he has endured as part of his centuries of police box travel. Later, the Doctor says that he knows the feeling when Dr. Constantine observes, “Before this war began, I was a father and a grandfather. Now I am neither. But I'm still a doctor.” Longtime fans could see this as a reference to the Doctor’s original companion, his granddaughter Susan, but this is actually the closest the Doctor has yet come to explicitly acknowledging that he had children as well as grandchildren.

That may seem like a ridiculous distinction to make: After all, how can anyone be a grandfather without also being a father? But such is the unease with which Doctor Who and its fans have long grappled with the question of whether the Doctor has sex—sorry, sorry, whether the Doctor dances. The fact that Susan was made the Doctor’s granddaughter in the first place was really in reaction to unease over the optics of a teenaged girl traveling with a much older man, and decision enshrined “No hanky-panky in the TARDIS” as an unofficial motto of the classic series. Even if not all of the Doctor’s incarnations are asexual—Tom Baker’s 4th Doctor often had a bit of apparent sexual tension with his companions, but then he did end up marrying one of them—it’s probably fair to say that at least some of them are. Really, of all the controversies that the TV movie created, there’s probably no bigger one than the decision to have Paul McGann’s Doctor engage in a couple of innocent, almost chaste kisses with his would-be companion. It’s a natural, probably long overdue progression of that to have Christopher Eccleston’s Doctor offhandedly declare that, at some point in his nine centuries of life, it’s safe to assume he’s danced. At the very least, he’s capable of being insulted when Rose suggests that it isn’t something he does.

Admittedly, based on his moves at the end of the episode, dancing isn’t something he does terribly often; there appears to be a good few centuries’ worth of rust that he’s trying to shake off. The simply fact is that the Doctor, through all his lives, has likely never been entirely averse to dancing, but he’s just never seen it as the most important thing he ought to be doing. When Rose tries to call his bluff in the hospital room, he is immediately distracted by her uninjured hands, which helps lead him to the crucial insight that ends up saving the day. It’s a convenient interruption, perhaps, but that’s the thing about saving the universe: It does tend to get in the way of whatever personal life you happen to have going on. How precisely that personal life involves Rose Tyler is a matter best left to another story and likely another Doctor, because the 9th Doctor, like so many of his predecessors, excels at changing the subject. After all, he’s proudest of his self-declared moves right as he’s about to send the upgraded nanogenes to repair the humans. Leave it to the Doctor to take something as pure and innocent as an extended sex metaphor and turn it into something cheap and tawdry like saving the world.

Stray observations:

- “Who looks at a screwdriver and thinks, ‘Ooh, this could be a little more sonic?’ “What, you’ve never been bored? Never had a long night? Never had a lot of cabinets to put up?”

- “I was going to send for another one but somebody’s got to blow up the factory.” “Oh, I know. First day I met him, he blew my job up. That's practically how he communicates.”

- “The last time I was sentenced to death, I ordered four hyper-vodkas for my breakfast. All a bit of a blur after that… I woke up in bed with both of my executioners. Lovely couple, they stayed in touch! Can't say that about most executioners.”

- Look at you, beaming away like you're Father Christmas!” “Who says I'm not? (Red bicycle when you were 12!)” “What?”

- “Rose, I’m trying to resonate concrete…”

Next Week: It’s all gone far too quickly, but it’s time to say goodbye to the 9th Doctor once more with Christopher Eccleston’s final three episodes. Join us for “Boom Town,” “Bad Wolf,” and “The Parting Of The Ways.”

“Everybody lives, Rose! Just this once, everybody lives!”