Doctor Who: “The End Of The World”/“The Unquiet Dead”

“The End Of The World” (season 1, episode 2; originally aired 4/2/2005)

(Available on Hulu, Netflix, and Amazon Instant Video.)

“Is that a technical term, jiggery pokery?” “Yeah, I came first in jiggery pokery. What about you?” “No, I failed hullabaloo.”

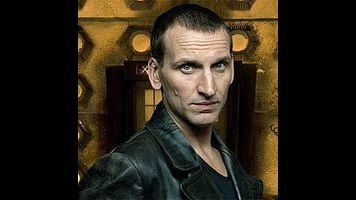

There’s a moment midway through “The End Of The World” that demonstrates why Doctor Who needed Christopher Eccleston to be the Doctor. As he investigates a panel, the intelligent tree Jabe informs him that she has learned what species he is, and she could scarcely believe the truth when she first saw the result of her scan. She asks no questions as to how the Doctor can be here when his very existence is impossible. Instead, she begs his forgiveness for intruding and, placing a hand on his arm, she tells him how sorry she is. Throughout this scene, the Doctor never says a word; indeed, his expression barely changes. But it is in that nearly imperceptible shift that Eccleston does all the acting he needs. A single ghost of a tear appears in his eye, and his normally hard features are transformed by grief. This might be the most subtle acting in Doctor Who’s entire 50-year history, and it speaks to the tragedy of this Doctor more than any big speech or emotional breakdown ever could. For those precious seconds, the Doctor’s protective barriers—his superficial goofiness and the abrasiveness only barely hidden beneath that—are removed, and it’s not easy to look upon the broken man who remains.

The second episode of new Doctor Who is even less concerned with plot than its predecessor “Rose.” There’s a mystery plot unfolding around the characters that involves metal spiders, sabotage, and murder, and there’s a convoluted explanation about how the Adherents of the Repeated Meme are actually under the control of the Lady Cassandra O’Brien, who is trying to fake a hostage situation until she switches gears to a stock market scam. Perhaps I’m being uncharitable with that synopsis, but the only phrase that really matters is “unfolding around the characters.” Davies’ primary concern is developing just who Rose and this particular Doctor are while also finding time to examine ancillary characters from Lady Cassandra to the doomed technician Raffalo.

Writer Russell T. Davies seems fully aware just how ludicrous the story’s premise is, playing up the ridiculousness with talk of the National Trust moving Earth’s continents back into their classic positions and artificially holding back Sun’s inevitable so that the galaxy’s wealthiest citizens could get the best possible show. A major goal here is to reveal just how weird and alien the revived Doctor Who universe can be. Rose may have dealt with Autons and the Nestene Consciousness, but those were monsters in present-day London; it’s quite something else to be approached by a fussy blue-skinned steward on a space platform five billion years in the future, and Rose’s culture shock is palpable as she is confronted with the event’s bizarre guests. The Doctor’s daffy enthusiasm stands in stark contrast to her bemusement, but Rose rallies quickly, especially when she learns from Raffalo that there are still plumbers five billion years in the future.

Much like “Rose” before it, this episode succeeds in the continued effort to reestablish Doctor Who in part because it doesn’t take any aspect of the show’s mythos for granted. While the gradual reintroduction of the words “Time Lord” is the most significant development here, the way the episode handles the question of how Rose can understand alien languages is particularly instructive. The TARDIS’ telepathic translation circuits were acknowledged exactly once in the first 26 seasons of Doctor Who, specifically in the Tom Baker adventure “The Masque Of Mandragora.” There, Sarah Jane Smith’s sudden curiosity about how she could possibly be speaking Italian is proof that she has been hypnotized, which not so implicitly dismisses the entire issue as a matter not worthy of serious discussion; the 4th Doctor calls this translation “a Time Lord gift I allow you to share” and sees no reason for further elaboration. That isn’t good enough for Rose, who points out that she never gave the TARDIS permission to get inside her head. It’s not a challenge that the series can do anything with long-term, or even really much beyond the scope of that conversation—new Doctor Who would be extraordinarily limited if the Doctor did turn off the telepathic circuits for Rose’s benefit—but it’s the best early indication that the revived series doesn’t plan on retaining elements of the original show simply because that’s how things have always been.

The question that “The End Of The World” dances around is just why the Doctor would choose to show Rose the destruction of her planet. After all, the Doctor only just witnessed his own planet burn, and it seems highly unlikely that he would wish to inflict such trauma upon a new companion on her maiden TARDIS trip. We can grant that the circumstances of the planets’ destructions aren’t analogous, but that isn’t really a sufficient explanation; again, out of everywhere in time and space, this is what the Doctor wanted Rose to see. The episode never quite provides an explicit reason, but it suggests several theories. At the beginning of the episode, he points out to Rose that the human race never even considers the possibility that they and their planet might survive all the way to their natural end. In that sense, Earth’s destruction is a victory, albeit one that can only feel like a triumph to someone as alien as the Doctor.

Indeed, his reaction to Earth’s death offers a window into the inner workings of the Time Lord mind. He told Rose in the premiere that he could feet the motion of the Earth and the universe around it; this trip might just be his way of offering Rose a glimpse of his impossibly vast perspective. The final scene, in which the Doctor returns Rose to present-day London and agrees to go get some food, further juxtaposes the contradictions of the Doctor’s worldview. He can move effortlessly from Earth’s fiery destruction to a bustling London street five billion years earlier, and his demeanor barely changes. He is equally at home in both places, in the cosmic and the in the mundane, and that implies he is not truly at home anywhere.

That ties back to his post-Time War trauma. If his moment with Jabe is the most vulnerable manifestation of his grief, then his treatment of the Lady Cassandra is the most unforgiving. As he harshly pronounces, “Everything has its time and everything dies.” His planet burned before its time, while Cassandra has long lived past hers. In comparison, Earth dying on schedule—give or take the National Trust’s gravity manipulations—feels right to the Doctor, a glimmer of cosmic order in a universe gone mad. “The End Of The World” neither challenges nor celebrates the Doctor’s decision to let Cassandra die. Rose, who was rightly disgusted by Cassandra’s bigotry, still implores the Doctor to save her, but the issue is dropped thereafter. This is the Doctor’s show and the Doctor’s universe, so he makes the rules, especially when he’s the designated driver. At this early stage in its revival, Doctor Who is a descriptive rather than prescriptive show. It wants the audience to understand the Doctor and the unearthly ways in which he responds to unearthly situations. It’s only with that knowledge that the audience—and Rose—can take that next step and understand why he is who he is. Until then, the tear in Christopher Eccleston’s eye tells us all we need to know.

Stray observations:

- The episode’s use of contemporary music like “Tainted Love” and “Toxic” as examples of Earth’s ancient ballads is just on the right side of the line between charmingly goofy and just sort of stupid. I think it’s Eccleston’s dancing (using the term as loosely as possible) that helps sell it.

- This Week in Mythos: The Doctor reveals that he’s a Time Lord and that the TARDIS is telepathic, but this episode is mostly significant for what it adds to the show’s mythology. We’ve got psychic paper, the Face of Boe, and the first, brief mention of the words “Bad Wolf.”

- The death of Jabe and the Doctor’s subsequent leap (or walk) of faith through the spinning blades is one of the stranger parts of the episode. It’s hard to know quite what to make of this sequence in literal narrative terms, but I’ve got to admit it feels right in terms of its development of the Doctor’s emotional journey.

- The Lady Cassandra effect looks great and creepy from a distance and looks unconvincing and creepy up close. Since it’s creepy in all cases, I’d say it gets the job done, but it’s another reminder of how far technology has progressed since 2005.

“The Unquiet Dead” (season 1, episode 3; originally aired 4/9/2005)

(Available on Hulu, Netflix, and Amazon Instant Video.)

“Aren’t you going to change?” “I’ve changed my jumper. Come on!”

“The Unquiet Dead” is the first of new Doctor Who’s so-called celebrity historicals, episodes that team up the Doctor and his companions with a recognizable figure from the past. This particular Who subgenre has a few antecedents in the classic series, but only a few; after the 1st Doctor’s early hobnobbing with Marco Polo and Emperor Nero, just about the only historical figure of any real significance who shows up in the subsequent two decades of the show is a young H.G. Wells in the much-derided 6th Doctor adventure “Timelash,” and even that story featured a young, pre-fame “Herbert” instead of the established titan of science fiction. While I have my issues with subsequent celebrity historical episodes, which could be overly reverential or simplistic in their treatment of their chosen subject, that isn’t the case with this first example of the form. Charles Dickens gets to play the hero—indeed, he ends up saving the day, or at least enabling Gwyneth to save the day—but a real effort is made here to capture the complexities of one of the great luminaries of 19th century fiction as he nears the end of his life.

It helps that the episode enlists one of the world’s foremost Dickens experts to play the part. Simon Callow had at least a decade’s experience performing as Dickens before he stepped into the role for Doctor Who, and that close familiarity is readily apparent in “The Unquiet Dead.” Indeed, there are times when Dickens threatens to take over the episode; his initial scene in his dressing room where he discusses his frustrations with the theater owner feels so disconnected from the adventures of the Doctor and Rose in the TARDIS. But then, part of the purpose of these early episodes is to reveal just how expansive the boundaries of Doctor Who’s storytelling actually are. For this week—hell, for this scene—the show can be a meditation on the life of Charles Dickens, and it’s under no obligation to be so again next week.

The Doctor’s own reaction to Dickens is carefully considered. While the 9th Doctor is all business whenever the ghosts are specifically on the move, he allows himself a few minutes’ fannish excitement when he barges his way into Dickens’ private coach. Perhaps unsurprisingly, Christopher Eccleston tends to be more convincing when portraying the deadly serious side of his Doctor, but one of his best playful moments in the role comes when he starts offering his gushing feedback to Dickens about “The Signal Man” and “Great Expectations”—although the Doctor proves that he has the right stuff to be a Doctor Who fan when he can’t help but point out how rubbish the American bit in Martin Chuzzlewit is. Dickens is the perfect straight man to the Doctor’s sudden exuberance, especially because the character never steps outside of his established for the sake of the jokes; indeed, Gatiss and Callow anchor Dickens’ funniest reactions—such as his declaration to the driver that “I think he can stay” after the Doctor showers him with praise—in terms of his previously established despondency. The scene in the carriage could easily just be two actors trading well-written banter, but the dialogue is informed by and builds upon what the episode has revealed about these two men as characters.

And yet, for all his obvious love of Charles Dickens and his books, the 9th Doctor has no patience for the man as a co-investigator of impossible mysteries. For the space of about 15 seconds, “The Unquiet Dead” appears to be gearing up for a fairly standard Doctor Who arc in which a skeptical supporting character comes to realize that the supernatural, or at least alien beings that resemble the supernatural, do in fact exist. But the Doctor is not as tolerant as he once was, snarling to Dickens, “If you’re going to deny it, don’t waste my time. Just shut up.” It’s a harsh moment, so much so that the Doctor apologizes to Dickens in the subsequent scene. This is an important moment for the new Doctor Who, because it signals that the arguments and conflicts aren’t going to be driven by plot but rather by character.

When the Doctor tells Dickens to shut up, he effectively speaks on behalf of the show, declaring that the denizens of this universe are entitled to their own reactions to the insanity unfolding around them, but not their own interpretations. Instead of getting mired in a debate about the nature of the ghosts, one in which Dickens would obviously be in the wrong, “The Unquiet Dead” pushes past that to the crucial monologue where Dickens explains why he cannot accept the existence of such spirits and the vast uncharted universe they represent. He asks the Doctor whether his decades of ignorance of such things mean that he has wasted life. Pointedly, the Doctor never answers that question.

It isn’t just Dickens who struggles to cope with the world that the Doctor inhabits, as Rose is deeply disturbed by the thought of the Gelth being given free rein to inhabit human corpses. The Doctor humors her for a bit longer than he does Dickens, but he still doesn’t see this as some high-minded rhetorical exercise; he offers the donor card analogy to prove his point to Rose, but he short-circuits the argument when she objects again by telling her that she is now dealing with a different morality, and that she can either get used to it or go home. This is such a clever moment because it demonstrates to viewers that Doctor Who is not fundamentally concerned with its own cleverness. There’s room to kick around the odd philosophical debate, yes, but the Doctor’s overriding priority is saving as many lives as possible, even if that involves making some superficially unpleasant compromises.

The question then is whether “The Unquiet Dead” lets itself and its characters off the hook by revealing that the Gelth are not nearly as innocent or benevolent as they first appear; indeed, when the Gelth make their move, their leader takes on the appearance of a smoky demon. This betrayal is arguably a dramatic necessity, as it’s difficult to see just how the episode could have reached a suitably exciting climax without some escalation of its primary threat, but it does make the Doctor look like a bit of a gullible idiot. But then, is that such a bad thing? After all, even if “The Unquiet Dead” has a more tightly developed plot than its two predecessors, what happens here is still fundamentally driven by the choices the characters make, and it’s instructive to see why the Doctor would make such a wrong decision for the right reasons. The still bears the weight of the Time War, and he feels deeply his responsibility to all the races that he and his people indirectly destroyed; in that context, it’s not really surprising that the Doctor is a little too quick to take the Gelth at their word.

And anyway, there are other ways for the Doctor to be right. He places his faith in Gwyneth and Charles Dickens, and they end up saving his life when he finds himself outmaneuvered. It may seem like the Doctor knows everything—he might even make that claim on occasion—but that isn’t really what the Doctor derives his power from. He believes in people, and he helps them find their best selves before it’s too late. If that means they end up preventing his death in Cardiff, then so much the better as far as he’s concerned.

Stray observations:

- As effective as the episode generally is, some of the disparate strands of “The Unquiet Dead” don’t quite fit together. Writer Mark Gatiss is relatively successful at finding common ground between Dickens and the Doctor, but the early antics of the undertake Gabriel Sneed feel like something out of a different, rather more explicitly comedic show. The obvious comparison here is the similarly macabre sense of humor that Gatiss displayed as one of the writers of the terrific sketch show The League Of Gentlemen, which was his major TV writing credit before being brought on for this story. As entertaining as it is, it doesn’t sit quite right with the rest of the episode.

- “Now, don’t antagonize her. I love a happy medium.” “I can’t believe you just said that.” I can’t either.

Time And Relative Dimension In Spoilers (Don’t read if you haven’t watched the rest of the new series):

For this week, I can’t really imagine a more appropriate spoiler section than yesterday’s “Day Of The Doctor” review. Indeed, after writing roughly 6,000 words on Doctor Who over the past few days, I don’t think I’ve got too much more to say about anything Who-related right now. So, next week, once I’ve had a little time to consider what the anniversary special means for the 9th Doctor’s era, I’ll be back with some more detailed thoughts in this space.

Next Week: We turn to the show’s first two-parter with “Aliens Of London” and “World War Three.” I’m alternately intrigued by and dreading the thought of revisiting this one, so it should be fun.