Doctor Who: "The Long Game"/"Father's Day"

“The Long Game” (season 1, episode 7; originally aired 5/7/2005)

(Available on Hulu, Netflix, and Amazon Instant Video.)

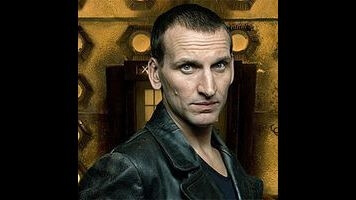

“Come on, how could you get on board without knowing where you are?” “Look at me. I'm stupid.”

Every episode in Christopher Eccleston’s single season as the Doctor has its own distinct identity. “Rose” is the one that restarts the grand adventure, while the subsequent episodes “The End Of The World” and “The Unquiet Dead” represent the show’s first journeys to the future and to the past. “Aliens Of London” and “World War Three” will forever be the ones that introduce the farting aliens—these aren’t always good identities—while “Boom Town”… well, we’ll get to that in a couple weeks. “Bad Wolf” and “Parting Of The Ways” are the grand finale, while “Dalek,” “Father’s Day,” and the two-parter “The Empty Child” and “The Doctor Dances” are the acknowledged classics. That just leaves “The Long Game,” which is just sort of there. It’s not a bad episode, exactly, but it feels inessential, especially when compared to the episode that it could have been. With precious little new to say about the Doctor or Rose, this episode is only as compelling as its guest characters—including Bruno Langley’s Adam Mitchell, Simon Pegg’s Editor, and Christine Adams’ Cathica, plus the Jagrafess—and those characters’ stories remain frustratingly unclear.

Now, it’s easy enough to understand why the Editor and the Jagrafess are in “The Long Game,” broadly speaking: It’s because they’re the baddies. As the Editor explains, the Jagrafess has used Satellite Five to stunt humanity’s growth and keep them unwittingly enslaved for the past 90 years, while the Editor himself is there to protect the investment in the Jagrafess made by a consortium of banks. That’s all fine and proper, but what precisely is the Jagrafess trying to accomplish in the long run? It’s the secret ruler of the Fourth Great and Bountiful Human Empire, but all it gets for its troubles is a miserable life cooped up in the ceiling of Floor 500. For that matter, if the Jagrafess is really so vulnerable to even a short-term malfunction in the cooling system, why exactly has the Editor, who hardly appears blessed with a surplus of loyalty, never bothered to shut off the air conditioning and seize power for himself? More to the point, how did the Jagrafess gain the support of an interstellar consortium when his most eloquent sales pitch seems to involve growling and thrashing about?

Make no mistake, I’m being pedantic here, as you can ask these sorts of questions of any Doctor Who story. (Except “The Caves Of Androzani.” That one is perfect.) Just looking back on the past six episodes, it’s not as though there was any deeply considered reason why, say, the Gelth are revealed to be evil. But such narrative fuzziness mattered less in “The Unquiet Dead” because, whatever their outward guise, the Gelth were consistently motivated by a need to survive, which is a primal enough reason that it demands little further justification. The motivations behind the Jagrafess and the Editor’s actions are far murkier; even if the viewer doesn’t pick up on any precise problems while watching the episode, the overall effect is that “The Long Game” has a weightless, ad hoc quality. The Jagrafess is the monster and the Editor is the villain simply because Doctor Who stories require such thing, and their plan is only as convoluted as it is because the Doctor and Rose need a mystery to solve.

That places a ton of pressure on Simon Pegg to compensate for these scripting shortcuts through sheer force of evil charisma, and he comes damn close to making his part of the story work. He plays the Editor as the sort of psychopath who derives real pleasure from skulking around a frozen control center and ordering about his mostly dead murder victims. He experiences a giddy thrill when he realizes he doesn’t know something; that reaction is only topped when he realizes the Doctor possesses infinite knowledge. His willingness to abandon whatever he and the Jagrafess are working on in Satellite Five to go around rewriting history—right up to wiping out humanity before it ever develops, which must surely represent the ultimate in self-loathing—suggests that neither of them is really all that committed to their current plan, and they’re just looking to be villainous on as big a scale as possible. If the script were just a hair more explicit about this, I’d say that the shapelessness of their evil might actually be intentional, a subtle pastiche of poorly motivated Doctor Who villains past. But if this episode is a parody, then it resembles too closely the source material it aims to deconstruct.

“The Long Game” might have the longest path from initial conception to broadcast of any story in the show’s history. Russell T. Davies originally submitted the story of an intergalactic news broadcaster as a spec script to the Doctor Who production office in 1987. When he ultimately revisited the idea, the story was first conceived as one told from the perspective of new companion Adam Mitchell, with a major point of emphasis being that Adam is not companion material. The idea that not everyone is worthy of traveling in the TARDIS is an intriguing idea to explore—and the Doctor’s absolute rejection of Adam adds some shading to his forgiveness of Rose in the subsequent episode—but the articulation of this notion in the finished episode isn’t terribly nuanced. The specific crime that the Doctor punishes Adam for is his attempt to transmit future information back to the 21st century; in the shooting script, it’s mentioned that part of why Adam wants this forbidden knowledge is because his father has a disease—arthritis, specifically—that is untreatable in 2012 but has long since been cured by the 2001st century. Without even a hint of such extenuating circumstances in the finished episode, it’s not possible to tell whether the Doctor weighs Adam’s actions or his motivations more heavily in making his decision, as Adam does the wrong thing for the wrong reasons.

So then, when the Doctor proudly announces that he only takes “the best,” what he’s really saying is that he doesn’t take lying, treacherous, amoral bastards. (Although let me introduce you to a chap called Vislor Turlough.) Which, fair enough, really, but that’s a rather obvious point to make. Even before Adam starts helping himself to future knowledge, he’s a distinctly unimpressive companion, fainting at the first sight of Satellite Five. He has exactly one moment where he shows any potential, and that’s when he asks why there aren’t any aliens on the station. Other than that, he’s useless. Given Adam’s clearly formidable technical skills, there’s a plausible version of “The Long Game” in which he is actually positioned as a more competent assistant than Rose—right up to the point where he gets a chip put in his head and he starts stealing forbidden knowledge. Or Davies could have stuck with his original idea, which was to tell the story from Adam’s perspective, depicting the Doctor and Rose as faintly terrifying, mysterious individuals.

As it is, this episode is decidedly unsubtle in its treatment of Adam, adopting the straightforwardly moralistic perspective that traveling in the TARDIS is a privilege that the Doctor has every right to revoke. It’s a fairly basic message and, in fairness, one that was perhaps appropriate for a 2005 audience that was still coming to understand what Doctor Who was all about. But such a straightforward moral should exist within a more complex narrative framework; “The Long Game” presents a few too many simple ideas, with the cumulative effect that this is a story that feels slight at best, underdeveloped at worst. The episode is hardly a failure, but it could have been so much more.

Grade: B-

Stray observations:

- “The Long Game” is also often mentioned as a satire of the

modern news media. I don’t really take issue with that description, as the

episode does present a bunch of journalists who believe their sole purpose is

to passively transmit whatever information is given to them, but, again, the

point isn’t developed much beyond that. It’s an element of the episode, yes,

but not an especially major one. - Speaking of the

journalists, Christine Adams turns in a nice supporting work as Cathica. Her

character arc is defined by her desperate need for promotion, which might be

another example of overly simplistic storytelling if not for her climactic

observation that they “should have promoted me years back.” It’s a clever line,

suggesting that, whereas once she wanted promotion as part of her blind

adherence to the status quo, now she is dangerous enough that the Editor should

have gotten rid of her when she had the chance. - Once more, with feeling: that’s the

Mighty

Jagrafess of the Holy Hadrojassic Maxarodenfoe. Max to his friends.

“Father’s Day” (season 1 episode 8; originally aired 5/14/2005)

(Available on Hulu, Netflix, and Amazon Instant Video.)

“The past is another country. 1987’s just the Isle of Wight.”

There’s an art to taking the drab and mundane and turning them

into something interesting, and that’s what director Joe Ahearne and the rest

of the Doctor Who creative team do with

the setting of “Father’s Day.” As Rose observes in the line directly before the

one above, the day her father died is just any other day, a dull autumn

Saturday that seems ill-suited to anything exciting or tragic. After making a

single Dalek seem like the scariest thing in the world in his previous

directorial effort, Ahearne frames and shoots this episode so as to emphasize the

crushing normalcy of the script. He’s ably assisted in that endeavor by Paul

Cornell’s script, which places Pete Tyler’s death in the context of Stuart

Hoskins and Sarah Clark’s wedding. This is very much a working-class London occasion,

one in which the father of the groom constantly grumbles about the rushed,

pregnancy-related circumstances behind the nuptials; one in which the attendees

wear their best clothes, which, if Pete’s suit is anything to go by, fall

somewhere between snazzy and cheap; and one in which depressingly few people

show up, though that may have something to do with the time-devouring monsters

flying overhead.

That gap between the larger-than-life and the

heartbreakingly mundane is where so much of the power of “Father’s Day” lies,

as Rose discovers when she finally meets the man she only knows as “the most

wonderful man in the world.” Far from the brilliant businessman and devoted

family man that Jackie described him as, Pete is a failed entrepreneur constantly

chasing get-rich schemes, and he only probably isn’t a philanderer. Even so, he’s clever enough to realize who Rose really

is—even given the hints of the paradox-sterilizing Reapers and her generally

bizarre behavior, it’s an impressive leap—and to realize who he really is or,

more accurately, who he isn’t. The scene

where he asks Rose to describe what he will be like as a father is full of conflicting

subtext. For all her disillusionment, Rose still paints a picture of the world’s

most perfect father; it’s such an obvious lie, one that she tells to herself

far more than she does to Pete. Her father already suspects that he was meant

to be hit by that car, and his daughter’s impossible story is sad confirmation.

That’s the real paradox of “Father’s Day,” and it has

nothing to do with time. After Pete’s death in 1987, Jackie and Rose spent the

subsequent 18 years building him up as the most wonderful man in the world,

someone who always came through when they needed him. It’s Rose’s belief in

that romanticized view of history that leads Pete to work out the truth,

because, as he puts it, “That’s not me.” But the mere fact that he’s willing to

throw himself in front of that car to save the world—or, more accurately, to

save the women he loves—is proof that he really was all the things his wife and

daughter always said about him. This season of Doctor Who has been defined by its ordinary heroes, those who take

inspiration from the Doctor and do the right thing when the Time Lord is unable

to. In some instances, that has made the Doctor look a tad inept, but not here.

This is Rose and Pete’s story, driven by the beautiful writing of Paul Cornell

and the nuanced performances of Billie Piper and Shaun Dingwall.

Indeed, the Doctor is frequently at his most alien and imperious

in how he seizes control of a situation that even he may not be able to put

right. For all his apparent coldness—and he has reason to be brusque, given

Rose’s betrayal of his trust—the Doctor is ultimately as compassionate here as we

have yet seen him be in this incarnation. Christopher Eccleston is given a

particularly lovely scene when the would-be newlyweds ask if he can save them,

and he asks who they are. The question sounds brusque, but it’s clear that he

really does want to understand, if only for a moment, the workings of such

achingly human lives. As he observes, “I’ve travelled to all sorts of places,

done things you couldn't even imagine, but you two. Street corner, two in the morning,

getting a taxi home. I’ve never had a life like that.” That little moment is a

poignant reminder that, no matter how much the Doctor might look like us, he is

not human, and so many tiny aspects of the human experience that we take for

granted lie forever beyond his reach. The scene works because Eccleston plays

it with just the right degree of wistfulness; he would fight to save anyone’s

life, but he considers especially important those that assume their simple,

ordinary lives aren’t important at all.

At the very beginning of the story, the Doctor is presented in

the most magical possible terms. When Rose asks if it would be possible to see

her father, he assures her that he can do anything, and he even invokes a genie

as he declares, “Your wish is my command, but be careful what you wish for.” On

some level, these lines turn the Doctor into an all-powerful plot device, as it

doesn’t really matter precisely how the Doctor manages to fly the TARDIS to

Jackie and Pete’s wedding or that fateful day in 1987. More than any previous story,

“Father’s Day” is concerned with a clear what-if question, and so it aims to

get straight to the point by bringing Rose face-to-face with her doomed father.

The opening scene is just the first of several instances in which Paul Cornell

emphasizes the emotional stakes over more plot-based concerns, which proves

crucial to making the story as a whole work. It’s not that “Father’s Day” is

any more illogical than any of this season’s other episodes, but its story

works more because it feels right

than because the morass of paradoxes is explained in exacting detail.

The Doctor’s lines also establish a parallel between his

relationship with Rose and the one that she forges with her dad. Cornell

presents multiple possible ways of thinking about the Doctor and Rose; Pete

himself assumes that the pair had had a lover’s quarrel when the Doctor storms

off, but the Doctor’s own words—“I picked another stupid ape!”—suggests the

Time Lord sees Rose as a glorified and highly disappointing pet. The Doctor’s

paranoia in that scene is heartbreaking, as he coolly points out that Rose

refused his invitation when she only knew the TARDIS could travel in space, but

she agreed when she learned it could also travel through time. The implication

is such a brutal inversion of the joyous emotions on display at the end of “Rose,”

and the Doctor quickly accepts her denial and moves on, but the damage has been

done.

And yet, the Doctor does later admit that he was never

really going to abandon Rose. He needs Rose to say that she’s sorry, and it’s

fitting that it’s only once they reconcile that the Doctor realizes his TARDIS

might be recoverable after all. It’s an open question whether the Doctor could

really hope to undo all the damage caused by the paradox-sterilizing Reapers,

as he claims; I tend to think that was wishful thinking on his part, a desperate

attempt to avoid the inevitable solution of Rose watching her father die once

more. But Pete’s words ring true here when he says that it’s his job for it to

be his fault, which is an apt description of how the Doctor has always seen his

relationship with his companions and, really, the universe at large. When the

Doctor places himself between the humans and a Reaper, declaring “I’m the

oldest thing in here,” his sacrifice is not necessarily a logical one,

considering he’s humanity’s last best chance. But logic doesn’t enter into it

when his surrogate children—whether you define that as just Rose or the entire

human race—are in danger, and he instinctively sacrifices himself just to buy

them some extra time. Pete Tyler’s subsequent decision to resolve the paradox

at the cost of his own life simply proves that the Doctor’s faith—his love,

even—was not misplaced.

Grade: A

Stray observations:

- Simon Pegg was apparently lined up originally to play Pete

Tyler, but scheduling conflicts meant that he ended up playing the Editor

instead. Given Pegg’s later rise to stardom (although he had already made a

name for himself by 2005 with Shaun Of

The Dead), it’s a bit hard to imagine him playing such a pivotal character

in the Doctor Who mythos. I suspect

he could have pulled it off, but Dingwall is so perfect in the role that it

probably all worked out for the best. - Camille Coduri deserves credit for her work here as both

versions of Jackie: the fed-up 1987 version and the nostalgic late ‘90s

version. She only really gets a single scene right at the end where she finally

understands what is going on around her, but she wrings real power out of her

final, brief goodbye to Pete. - It’s a great gag to have a very young Mickey running around

the church, with Rose imprinting on him like a mother hen. That said, it may be slightly overdoing the joke when Jackie

actually says, “God help his poor girlfriend if ever gets one.” - This Week in Mythos: These

are two of the more self-contained episodes in the first season, but we do see

the Face of Boe on Bad Wolf TV in “The Long Game,” while “Father’s Day” reintroduces

certain key rules of Doctor Who time

travel. Although the Reapers are new, the Doctor’s prohibition on Rose touching

her younger self recalls the Blinovitch Limitation Effect.

Next Week: We reach one of the show’s all-time classics, “The Empty Child” and “The Doctor Dances.”