Doctor Who trades epic for personal in a poignant finale

This story was never about Gallifrey. As far as the Doctor is concerned, his home planet is somewhere between a distraction and a means to an end. For anyone hoping for big revelations in the wake of Gallifrey’s return, that’s bound to be a bit of a disappointment. After all, this surely must be what the show has been building toward at least since “The Day Of The Doctor,” and arguably from the very moment back in Christopher Eccleston’s year in the TARDIS that we learned the Doctor was the last of the Time Lords. The proper, official return of the Doctor’s people is the culmination of a ten-year story, and it makes sense for audiences to be interested in that, especially when you throw in the season-long arc about the Doctor and the hybrid. But, as the Doctor makes clear in the Cloister, none of that matters to him, at least not right now. Ken Bones is back as the general from the 50th anniversary special, and Donald Sumpter, Game Of Thrones’ Maester Luwin, takes over for Timothy Dalton as Rassilon, the resurrected founder of Time Lord society last seen in “The End Of Time.” The Doctor summarily banishes one of those characters and mortally (or at least regeneratively, giving us our first onscreen regeneration that changes a Time Lord’s race and gender) wounds the other, yet both still feel like sideshows. Gallifrey and its absence have long defined the new series Doctors, yet when he finally makes it home, he doesn’t care. He only cares about saving the life of his best friend, and he will break all of his rules to do so.

The result, then, is that the audience is invited to think going in that “Hell Bent” will be an epic finale along the lines of, say, “The Big Bang” or “The Wedding Of River Song,” only for the show to swerve toward something closer to the sustained heartbreak (admittedly still mixed with plenty of narrative pyrotechnics) of “The Angels Take Manhattan.” The framing device of the Doctor telling Clara the story of their parting is the first clue that this episode is far more about their relationship than it ever was about Gallifrey, but it’s fair to say that “Hell Bent” delivers something rather different from what it and the episodes building up to it appear to promise. This definitely isn’t the first narrative swerve in new Doctor Who, and in the Moffat era in particular, and this is actually one of the better-executed examples, if only because what we get in the second half of the episode is so compelling. Where “Hell Bent” errs is in its lack of narrative signposting, as we’re about a half-hour into the story before the Doctor makes absolutely clear that he’s here to save Clara, rather than deal with the prophecy of the Hybrid. The Doctor’s silence in the early going certainly contributes to the Western atmosphere, but it creates ambiguity as to what he’s actually so furious about. Ohila of the Sisterhood of Karn suggests the Doctor holds Rassilon alone responsible for the Time War, but there’s good reason to think that’s beside the point, and that it’s really all to do with the confession dial, considering the Doctor is shown holding it in the barn and it dominates the conversation when he and Rassilon meet face to face. Basically, “Hell Bent” is coy about its actual story for no particular reason beyond the fact that Steven Moffat sometimes likes being coy, and this somewhat detracts from what really does end up being a fantastic story.

There’s a bait and switch in this episode, no question. Hell, there might be three or four of them, depending on how you count them. As far as Gallifrey is concerned, the crucial misdirection spins out of the very end of last week’s “Heaven Sent,” as the Doctor addressed his Time Lord tormentors after escaping the confession dial: “The Hybrid destined to conquer Gallifrey and stand in its ruins is me.” (Or “Me.” We’ll get back to that.) Naturally enough, the audience focused on the Doctor’s words, yet they were beside the point. It was his tone that mattered. For all his triumph as he finished his billions-year story about the bird and the diamond mountain, his tone as he addressed the Gallifreyan boy and the confession dial suggested a man far beyond mere words like “anger” or “rage.” The Doctor of “Hell Bent” is traumatized and broken, and his inability to let Clara go is what ends up driving the story, even as the entire rest of the universe, Clara very much included, tells him he has to accept the horrible truth. All the business with prophecies and hybrids and Time Lords is only so much window dressing.

In that sense, “Hell Bent” works for Gallifrey much as “The Magician’s Apprentice”/“The Witch’s Familiar” did for Davros and Missy, as these stories transform them into potential recurring presences without undercutting their narrative importance. Gallifrey is now in a position where it can return in any subsequent story, but that doesn’t undo how significant the planet remains in the larger mythos of the show. Maybe “Hell Bent” throws away a story worth telling in which the Doctor had more fully focused on finding Gallifrey, or even just one in which the Doctor dealt more directly with the fallout of the Time War, but tonight’s episode effectively suggests there isn’t much else left to say about that. Or, at least, the Doctor has much more important things on his mind, starting with saving the life of his friends. What “Hell Bent” ends up disproving instead is something the new series implicitly supposed when it destroyed Gallifrey in the first place, namely that Time Lords can’t represent a compelling presence in the show, either as outright villains or as uneasy allies. To be sure, there’s some of the dusty senators and stilted mysticisms about tonight’s episode, particularly when Rassilon and Ohila are arguing, but the episode manages to present more of the workings of Time Lord society than we’ve ever seen onscreen, and much of it suggests worthwhile stories are waiting to be told on this world.

Indeed, the Doctor’s largely silent trip to the Dry Lands and the barn—previously seen in “The Day Of The Doctor” and “Listen”—suggests more about his past and the structure of Time Lord society than nearly anything we’ve seen in the show’s 52 years, even if the show (and the Doctor) says almost nothing out loud. It’s never said explicitly, but “Hell Bent” comes closer than any other episode to clarifying that Gallifrey might be the home of the Time Lords, but not all Gallifreyans are Time Lords. The episode builds implicitly yet strongly on what we glimpsed of the Doctor’s childhood in “Listen,” and the presentation of the Doctor as a war hero equal parts respected and feared by those he served with is a detail worth exploring in future, as it creates a totally different context for this character we otherwise know so well. Between that treatment and the Doctor’s general conduct once he seizes control of Gallifrey, there’s a good argument to be made that Gallifrey is the one place in the universe where the Doctor can never truly be himself: He can be an old warrior, or a legendary hybrid, or the Lord President, or just a broken old man, but he sure as hell isn’t the Doctor. Again, that’s an idea worth developing down the line, but it works just fine here in support of the more targeted story of the Doctor’s efforts to rescue Clara.

One controversial aspect of this episode—certainly the bit I’m still struggling to sort out for myself—is the decision to bring back Clara. The ending of “Face The Raven” was a beautiful, powerful 10 minutes of television, and it’s worrisome to think that “Hell Bent” might unring that bell. On balance, I don’t think it does, unless someone feels that ending was powerful exclusively because Clara died. Yet I would say the fact of her death was less important to the poignancy of “Face The Raven” than was the way in which Clara prepared for her death, how she demanded the Doctor give her the right to choose what meaning her death would have. “Face The Raven,” “Heaven Sent,” and “Hell Bent” suggest the fundamental conflict between those who have nothing left but to be remembered and those who are left behind to do the remembering. Clara asked the Doctor to remember what she stood for, both so that he can know Clara died because of who she was—a point Ashildr reiterates here—and so that he can find the inspiration he needs to keep being the Doctor. He appeared to find that at the climax of “Heaven Sent,” but that peace of mind abandons him when he confronts his tormentors here and sets into motion his plan to save Clara.

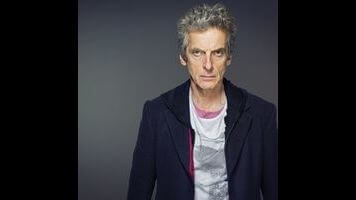

What makes so much of this work are the performances from Peter Capaldi and Jenna Coleman. The Doctor’s anguish is palpable, and his incarnation of the Time Lord is better equipped to linger in heartbreak than his immediate predecessors. When we talk about this being a more straightforward version of the Doctor, what’s on display here shines through, as the Doctor struggles to convince Clara that he even slightly knows what he’s doing. He raises his voice, and he angrily claims there is no one for him to answer to, when the look in Clara’s eyes makes it clear there’s absolutely still one person left. Before that, he is circumspect even by his standards, refusing to give straight answers to even the most basic questions. The episode has some fun with this—it’s a fun gag when the Doctor admits that saying precisely what the Cloister and the Matrix are hurts him a bit—but the episode soon reveals that the Doctor can barely face the reality of what the Time Lords did to him, and how well-earned Clara and the universe’s hatred of the Time Lords really is.

As for Clara, her role here is, logically enough, an extension of the end of “Face The Raven,” as she tries to convince the Doctor that it’s not worth burning his world and all he stood for just to hang on to her. The Doctor and Clara both recognize that he’s doing this as much for himself as he is for her; she does try to get some sense into him, yet she also recognizes how much he has endured and will yet endure with her inevitable death. Clara is never going to be in that first tier of companions, because the show never brought her character arc into a single clear focus, yet the show did end up finding something special between Clara and this Doctor, as their friendship created both incredible depth of caring and a very real danger that each would spur the other toward disaster. Clara and the Doctor will always stand by each other, which is why they no longer can. “Face The Raven” used Clara’s death to illustrate that point, “Heaven Sent” seized upon the Doctor’s grief, and now “Hell Bent” reverses one without undoing the other. If anything, bringing Clara back only serves to amplify the Doctor’s pain, or at least bring it closer to the surface, which is where it really ought to be in a television story.

You could compare a lot of this with past new series companion exits: Rose’s heartbreaking parting followed by a seemingly impossible return, Donna’s memory wipe, Amy and Rory’s exit leading to the Doctor withdrawing from himself and the world, even Martha’s recognition that the two of them just aren’t right for each other. Without quite saying that Clara’s exit improves on them all, the show has definitely learned some valuable lessons from what worked and what didn’t. Clara’s return is far better than Rose’s because it’s the direct result of the Doctor’s onscreen action, rather than something just kind of mentioned offhandedly, and “Hell Bent” becomes all about the Doctor and Clara talking out what they mean to each other and why the must part, whereas “Journey’s End” goes perversely out of its way to minimize Rose and the 10th Doctor’s interactions. The Doctor’s actions here play far better than the century-long grieving (possibly sulking) of “The Snowmen,” because again we actually see it, and because it directly drives the plot instead of being this thing distracting from the inevitable business of the Doctor moving on. And tonight’s episode alludes to Donna’s fate in “Journey’s End”, taking a lot more care than that last time to consider what the companion wants in all this.