Doggystyle changed the way hip-hop reckoned with nostalgia

Permanent Records is an ongoing closer look at the records that matter most.

Hip-hop has a complicated relationship with nostalgia. For most of its three-and-a-half decades, it’s been committed to relentless forward progress and the continuous exploration of new sounds and styles, showing not only little interest in reviving any of its past triumphs but actual antipathy to the whole concept. Hip-hop culture revered certain high points (the peak era of the Native Tongues collective, Illmatic, the collected works of Rakim), but for the most part it’s treated looking backward like it could turn you into a pillar of salt. Even when beat-makers raided their parents’ record collections for samples, the results often gave the source material an ironic flip, like the gangsta rap trope of using sunny soul songs an MC grew up on to emphasize exactly how far they’ve drifted from a state of childhood innocence, and to cast a veil of skepticism over the very idea that someone could be innocent at all.

It took about 30 years for this resistance to nostalgia to start breaking down as rap’s first generations of artists—raised on soul, funk, and R&B—have begun to be replaced by rappers who grew up on rap. (Compare this to sentimentality-prone rock ’n’ roll, which got from “That’s All Right” to Sha Na Na in half that time.) In 2015, rappers don’t have to worry about being clowned as biters for quoting someone else’s lines, or called corny for going in over a vintage boom-bap beat while rocking a high-top fade and Space Jam Jordans.

Like the first wave of punks in the ’70s, rappers emerging today have discovered the potential of traveling backward toward their genre’s roots as an act of rebellion against the aging monoliths in power, with their propensity toward grandiose aesthetic statements and millionaire ennui. The biggest beneficiaries of this new nostalgic bent are Biggie and Tupac, who conquered the pop charts for hip-hop but died before they started rapping about Picassos. Alongside Kurt Cobain, they complete the trinity of ’90s pop-star martyrdom.

Right behind them is Snoop Dogg, who’s managed to elude staleness with silky, pimp-like grace over the course of a career that’s older than most of the rappers he’s competing against on the charts. No rapper of his generation has been as big for as long as he has, and other rappers are becoming more brazen about borrowing moves from the early days of his career to further their own. You can see it in Wiz Khalifa’s louche stoner persona and A$AP Rocky’s commingling of street style and sumptuous luxury, and you can hear it echoing it all over the radio.

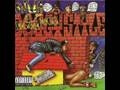

Doggystyle is an odd subject of a retro revival because the album itself is more thoroughly steeped in earnest, un-ironic nostalgia than any other rap record of its time. It was Snoop’s attempt at not just referencing the classic funk albums of the George Clinton era, but to come as close as he could to actually making a George Clinton album, from the “Atomic Dog” quotes worked into the hand-drawn album art to the woozy party vibe that runs through nearly every song (including an appearance by Clinton himself).

The G-funk sound that Dr. Dre pioneered and helped turn into the biggest non-grunge sound of the ’90s was marked by an eerie detachment from the vintage records it was based on. The style’s most successful cuts, like Dre’s “Nuthin’ But A ‘G’ Thang” and Warren G.’s “Regulate,” are marked by a sense of alienation and anxiety, and gave off the impression of listening to an incredibly well-curated oldies station while under the influence of a strain of marijuana specifically engineered to induce maximum paranoia. For the most part Doggystyle, avoids the darkness and keeps the source material’s earthy, organic grooves intact. The sound is thick, super-saturated, and unabashedly approachable, with its cartoonishly wobbly bass lines and pitch-shifted vocals. On many of the songs, Dre doesn’t even switch up the beats to conform to rap standards. On the lead single “Who Am I (What’s My Name)?” Snoop goes in over a gliding rhythm straight off a ’70s dance floor. On the Slick Rick-quoting “Lodi Dodi,” which over the years has emerged as a fan-favorite deep cut, there’s barely a beat at all.

For a record made at the peak of gangsta rap’s first wave (and at the onset of the East Coast-West Coast feud), it’s noticeably light on violence. Most of the songs have a line or two about guns, but only a couple actually revolve around them, and aside from the spooky morality tale “Murder Was The Case,” where Snoop portrays himself as the victim of violence rather than its proud perpetrator, they’re the least memorable parts of the album. If the party from “Gin And Juice” happened on an Ice Cube or Biggie album, it probably would have ended in a spray of gunfire in order to teach listeners a lesson about never letting your guard down, and to underline the fleeting nature of happiness in a world full of wicked men. Snoop, on the other hand, simply dips out.

Snoop was already a massive pop star by the time he made Doggystyle, but it would be hard to tell by the lyrics alone. There’s plenty of boasting on it, but it centers around how charming and altogether amazing Snoop is. (He hits the nail on the head when he calls himself a “conceited bastard” on “Lodi Dodi.”) Materially, it’s an strangely humble work. On record, Snoop mostly makes himself out to be just a dude hanging around the neighborhood—no mansions, no designer clothes, no modern art collection—despite whatever changes in circumstances he’d experienced post-“‘G’ Thang.” Doggystyle is concerned with relatively humble pleasures: hanging out, getting high, getting laid, the feeling when your homie shows up at your place with a bottle of liquor and a bag of good weed.

Between its blithe debauchery and seemingly endless supply of jokes about balls, Doggystyle is as proudly adolescent a record as its title suggests. Combined with the relatively idyllic portrait he paints of ’hood life (as opposed to the hellish dystopia portrayed by other gangsta rappers and the mass media in general), it gives the sense that Snoop was trying as hard as he could to hold on to some sort of blissful pre-fame existence where he wasn’t embroiled in a heated (and soon to be fatal) rap beef and hounded by police gunning to take down a celebrity who rapped about killing cops.

Whatever the source was of Snoop’s particular nostalgia for his life before he became a celebrity, Doggystyle seems to have worked it out. Although he’s retained his retro affectations—his pimp suits and vintage Cadillacs—he’s let go of his carefully constructed image as a regular dude who throws parties at his momma’s house and still gets around by catching a buck on a friend’s handlebars and instead embraced the potential that celebrity affords to live a surreal existence beyond the imagination of the average person, possibly more so than any other celebrity alive. He’s made records with a baffling range of musicians, from Flying Lotus to Katy Perry. He’s appeared on Sesame Street and in his own line of Girls Gone Wild DVDs. He’s moonlighted as a stand-up comedian, a talk-show host, and a pimp. He’s been turned into a cartoon, and he’s made himself over briefly as a Rastafarian. And by doing all of these absurd things, he’s become one of the most famous people on earth.

It’s this Snoop, who seems to exist on his own plane of possibility, that rappers want to be like. But it’s Doggystyle that they’re trying to sound like.

The most brazen attempt so far at replicating Doggystyle’s funky magic comes from an unexpected source. Kendrick Lamar’s To Pimp A Butterfly has been roundly praised for its avant-garde sonic flourishes and its timely examination of what it means to be black in America, but look closely at its structure and you’ll notice that much of it was lifted straight from Snoop. It comes through clearest on “King Kunta,” a dizzily psychedelic fever-dream re-imagining of “Who Am I (What’s My Name)?” as a defiant statement of black pride (with a lyrical reference to “Murder Was The Case” to boot). The Doggystyle influence runs deeply throughout the record, with funky bass lines descended directly from Dre’s Moog re-creations of Bootsy Collins parts. There’s a palpable denseness to the production and mix, which flouts the current trend of elegantly minimalist rap beats. There’s even something to the way that the poem Lamar repeats throughout the record fits next to the tracks that recalls Doggystyle’s skits, even though there aren’t any ball jokes in it. (And of course there’s an appearance by Snoop Dogg himself.)

The strongest link between Butterfly and Doggystyle is the potent use of nostalgia as a means of escape from the here and now. Lamar’s range of apparent influences is broader than Snoop’s, and his purposes for invoking them in order to step outside the moment are different—he uses the change in perspective to study America’s racial hang-ups as opposed to Snoop’s pure escapism—but it’s mostly the same thing. The only major difference is that Snoop was trying to evoke a time when people listened to funk records, while Lamar’s nostalgia is for when they heard them through Doggystyle.