Don't expect any Black Stallion magic from Lean On Pete's shatteringly sad boy-and-his-horse story

Just about every scene in Lean On Pete, the sensitive, unvarnished, at times powerfully sad new drama from writer-director Andrew Haigh (Weekend, 45 Years), reveals something small but important about the hardscrabble lives it chronicles. We know, for example, that scrawny, 15-year-old Charley (Charlie Plummer) is an athlete who’s new to town, because we first see him arranging trophies on a windowsill, then running down a driveway, past a recycling bin overstuffed with broken-down, folded-up moving boxes. “You don’t need to keep cereal in the fridge,” insists the married woman (Amy Seimetz) his rapscallion single father (Travis Fimmel) has brought home. But if they don’t, Charley explains, the roaches will get into it. Haigh’s storytelling is fittingly economical—he doesn’t waste a shot, a line of dialogue, an opportunity for a telling detail. His characters, after all, can’t afford to waste anything.

“Spokane, Washington” reads Charley’s team T-shirt. But it’s Portland where he and his father have landed for now. (They move around a lot, we eventually learn.) On one of his morning runs, Charley stumbles upon the local racetracks and meets Del (Steve Buscemi), a grizzled crank who earns his living on the circuit, carting bottom-rung racehorses from town to town, aiming to make just a little more than what he spends. Is there tough love beneath his bitter exterior? Buscemi, summoning the intense irritation that he’s played for exquisite comedy in everything from Fargo to the recent The Death Of Stalin, leaves the question open, even once Del offers Charley a few bucks a week doing odd jobs on the road and in his stables. The boy ends up bonding with one of his new boss’ overtaxed meal tickets, a gentle quarter horse named Lean On Pete. “They’re not pets,” aging jockey Bonnie (Chloë Sevigny) warns him. But how can Charley not get attached? They’re runners, him and the beast both.

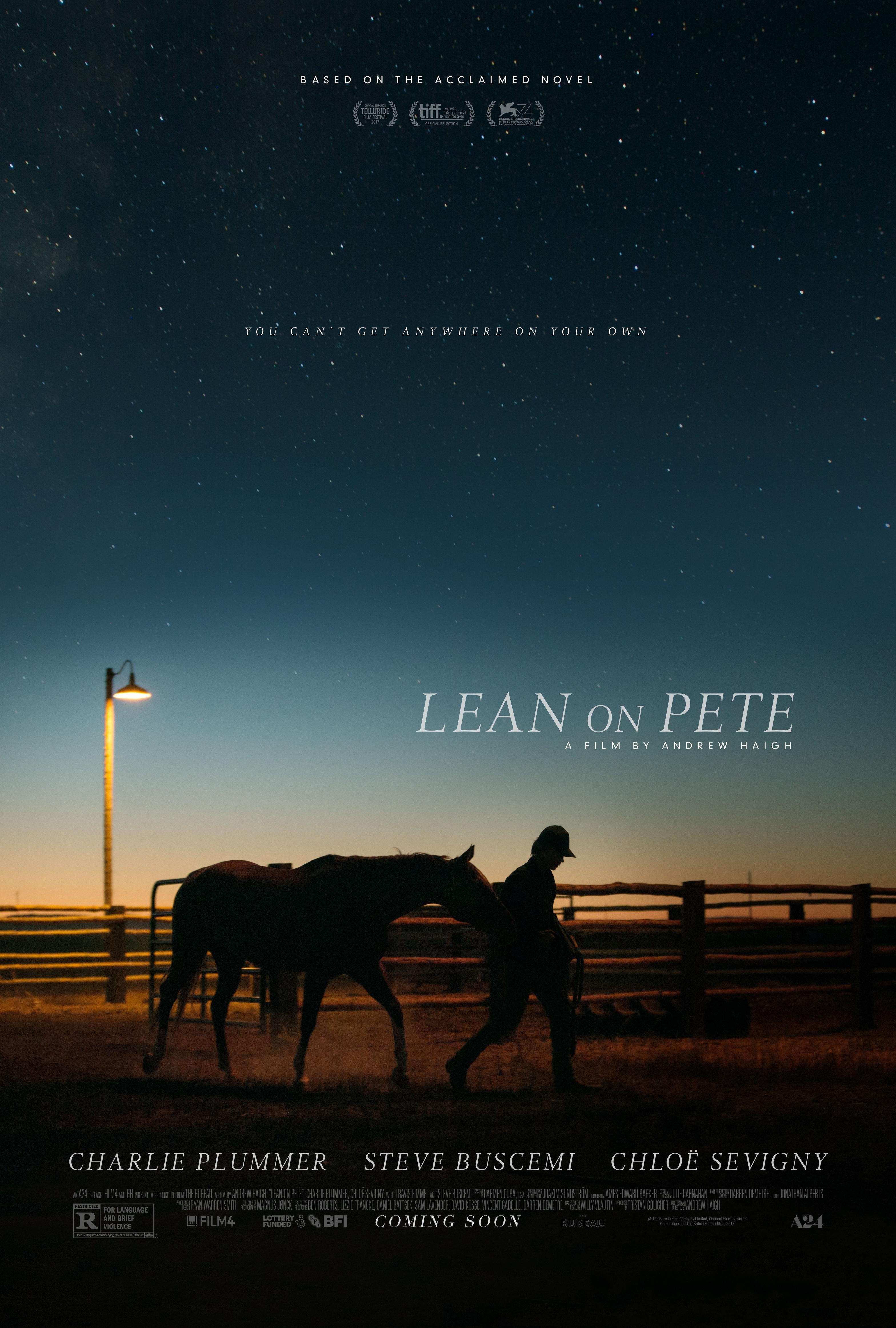

The lonely teen boy, the long-shot steed on its last legs, the surly mentor figure softening after years of hard times: All of this sounds like a tearjerker we’ve seen before. But Lean On Pete, drawn from the pages of a novel by author and alt-country singer Willy Vlautin, isn’t here to warm hearts. It’s as unsparing and unsentimental as Buscemi’s weathered race-circuit veteran. That’s perhaps to be expected from Haigh, a British filmmaker fast specializing in harsh insights, achingly intimate literary adaptations, and the subversion of typical movie relationships. 45 Years, his last film, was existential nightmare fuel for marrieds, a domestic drama that slowly dismantled the comforting ideal of growing happily old together and remaining content after decades of monogamy. Here, Haigh sidesteps romantic baloney at every turn. Lean On Pete is the first movie he’s made in the States, and it belongs to a rich tradition of second-hand Americana. Are outsiders looking in best equipped to see both the mythic grandeur of this country—the vast expanses of sky and land that Haigh gets lost in, capturing their scenic pleasures from afar and at dusk—and the tough truth about how so much of its people live?

As the plot trots in new directions, episodically sprawling across the Pacific Northwest, Lean On Pete finds beauty and melancholy in the “asshole of nowhere,” neither insulting nor romanticizing the working-class America it depicts in granular, pointed detail. It’s an apolitical portrait, ostensibly; few hints of the currently raging culture wars—or of ugly racial animosity, openly stated or disguised as patriotic rhetoric—creep into this depiction of honest-to-God “economic anxiety.” But Haigh’s interest in the battle between compassion and self-interest, the conflict raging in Del’s heart and defining nearly every one of the film’s encounters, is a crucial one for our here and now. What could have turned into War Horse without the war lands closer to the crushing spirit of Bicycle Thieves, that classic neorealist trudge about the zero sum game of poverty, the way society pits the down-and-out against each other.

The film owes much of its naturalism to its mix of familiar faces and expressive unknowns, led by Plummer, who played the kidnapped Getty kid in All The Money In The World, and who here delivers a performance of quiet, quaking vulnerability—a constant staving off of total desperation. As Lean On Pete slops hardship upon hardship, piling on only in the way life on the fringe sometimes does, it becomes increasingly clear that the film’s eponymous animal, true to his name, is a kind of living, breathing crutch for young Charley—something for this damaged kid, whose home life dramatically worsens as the movie progresses, to invest all his emotional energy into. What we’re watching, in other words, is less “boy and his horse” than “boy and the one emblem of purpose keeping him from tumbling into an abyss of despair.” That makes Lean On Pete more than a tearjerker; it’s a heartbreaker through and through. We watch and wait for a silver lining in the film’s storm clouds, hoping for a happy ending the movies can provide but lives this hard often don’t.