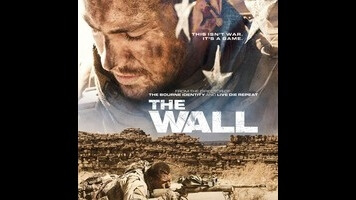

Doug Liman’s wartime sniper drama The Wall hits its mark when trusting its action

Directed by Doug Liman (Edge Of Tomorrow) from a script off of Hollywood’s famous Black List of un-produced screenplays, The Wall presents America’s protracted war in Iraq in primally simple terms: two U.S. soldiers fighting (and maybe dying) for reasons they can’t articulate, pinned down by an enemy they can’t see or understand. In its white-knuckle economy, the film breaks from the limply well-meaning Hollywood polemics that marched steadily into theaters a decade ago, like waves of advancing troops. The problem with Lions For Lambs or In The Valley Of Elah or Stop-Loss was that they were so busy functioning as screeds—abstracting the war itself into outraged talking points—that they forgot to function as, well, movies. In its best moments, The Wall is just a movie, a tense and nasty black-box thriller that conveys its politics through the microcosmic stakes of its life-and-death scenario. Pity that when the characters open their mouths, they sometimes unleash some very heavy-handed artillery, their speech coated too often in cliché.

The film spans a few hours of a single day, sometime during the closing weeks of 2007. The war is winding down (officially, anyway), but not for Army ranger Sergeant Isaac (Aaron Taylor-Johnson) and his commanding officer, sharpshooting Sergeant Matthews (John Cena), who find themselves scanning the perimeter of a pipeline construction site, looking for whoever left behind a pile of bodies. From the moment the two drop their guard and deem the area safe, they become walking emblems of a premature “Mission Accomplished.” It’s the whiz of a bullet, right before impact, that announces their mistake. By the time the boom of the rifle follows, echoing across the barren sprawl of the desert like a rejoinder, Matthews is already face down in the dirt, in danger of bleeding out. Coming to his aid, Isaac is hit too, and quickly takes cover behind a crumbling stone wall, taunted over the radio by the Iraqi sniper (voice of Laith Nakli) who’s lured them into their own personal quagmire.

For almost 90 minutes, we’re right there on the “safe” side of the barrier, watching this injured soldier try to think his way out of an impossible ordeal. Isaac is resourceful and resilient, but he’s no super commando. We see the pain and fear scrawled across his sweaty features; when he has to remove the bullet from his leg, it’s not with badass steely conviction, but the sobbing convulsions of real agony. The Wall is almost cruelly committed to demonstrating Isaac’s vulnerability, his limitations, his very human fallibility. Heroism doesn’t factor into the characterization, either: Finding the rare proper use for his beefcake blandness, Taylor-Johnson plays Isaac as the unquestioning model soldier, following orders and unconcerned with politics. More conventionally, the film also teases out a dark backstory, as though the inherent drama of the situation also required some tortured personal motivation.

The Wall fancies itself a battle of wits as much as a sniper duel, but it’s not really a fair fight. Because if Isaac is admirably rank-and-file ordinary, his opponent is closer to pure bogeyman. Screenwriter Dwain Worrell (Netflix’s Iron Fist) toys with the idea that he may be fabled insurgent shooter Juda, whose real-or-fabricated kill count and allegedly expert aim earned him a wartime reputation on par with Chris Kyle’s. The Wall visualizes him only through his predatory crosshairs, panning across Isaac’s unstable sanctuary like Jaws hunting for skinny-dippers. And when he speaks, it’s through a calculated mixture of mind games, Edgar Allan Poe quotations, and grandiose statements straight out of the Bond-villain handbook. (“We are not so different, you and I,” goes an actual line of unironic dialogue, though since the character remains perennially off camera, maybe we just can’t see him doing air quotes.) At the same time, Worrell supplies this mystery marksman with his own hint of traumatic motivation, a half-measure toward rationalizing his murderous rage. But empathy only goes so far when you’re talking about a literally faceless foe, the disembodied menace of Middle Eastern conflict.

So perhaps it’s no great mystery why The Wall languished in Black List purgatory; some scripts go un-filmed for a reason. All the same, Liman rises to the challenge of his one-location war movie, making a vast stretch of arid land feel downright claustrophobic and staging episodes of hair-trigger suspense with the same control he brought to the sniper scenes of the original Bourne Identity. (He also omits music from the soundscape—an act of Hitchcockian gutsiness.) Up through its daringly abrupt ending, The Wall works when simply trusting a potent premise and a one-on-one vision of modern warfare to do all the talking. Its words miss the mark.