Unfortunately for Fessenden, he was a bit ahead of the reanimated curve. And so, after failing to secure financing for Depraved the first time around, the film comes to us more than a decade later as an independently funded project. The Middle Eastern conflicts that inspired the story are still ongoing, and the pharmaceutical companies that play the villain here have, if anything, only gotten more malevolent in the past decade and a half. So while Fessenden’s Depraved tale of a doctor driven mad by PTSD, his morally bankrupt business partner, and the poor schmuck who wakes up with his brain in another man’s body is an undoubtedly stitched-together affair, its relevance to the current moment is similarly undeniable.

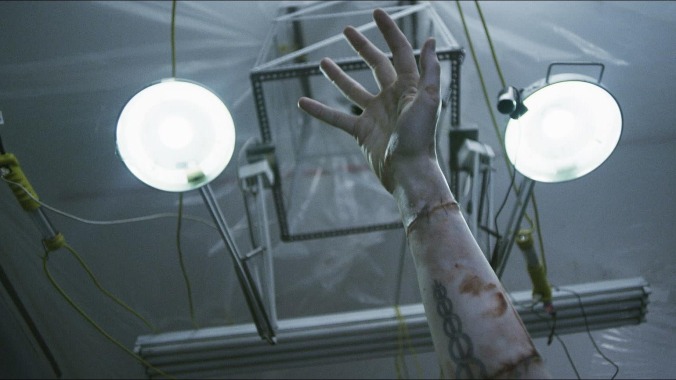

Depraved is at its most compelling when it concentrates on the romantic side of the monster, who as the film opens has not yet been (re)born. That’s because Alex (Owen Campbell), whose brain will power the creature soon to be known as Adam (Alex Breaux), isn’t dead yet, and in fact is busy celebrating his birthday with girlfriend Lucy (The Ranger’s Chloë Levine). That celebration turns into an argument about commitment, and Alex sullenly stomps out of Lucy’s apartment with her birthday gift to him—a pendant on a silver chain—around his neck. Before he can text her an apology, however, a shadowy figure runs up to him and stabs him repeatedly in the stomach. The attacker’s motive isn’t robbery, as Alex realizes when he wakes up in a gray, waxen body made up of the sewn-together parts of multiple men. A few moments later, he’s greeted by awestruck ex-combat doctor Henry (David Call), who tells him that his name is now Adam.

Alex/Adam’s slowly rebuilding consciousness will eventually lead him back to Lucy. But in the meantime, Fessenden, who serves as writer, producer, and editor as well as director, puts the viewer inside Adam’s head with experimental editing techniques reminiscent of Stan Brakhage, conveying his pain and confusion with dizzying collages of anatomical diagrams and abstract shapes. Depraved is a film with a small cast and limited locations—practicalities dictated by its budget, one assumes—and much of the first half of the film is a two-hander as Adam and Henry do puzzles, play ping-pong, and rebuild Adam’s vocabulary within the walls of Henry’s shabby Brooklyn loft/laboratory. In a counterintuitive twist, the film gets less compelling as it pulls back from this intimate environment, introducing Henry’s bloviating business partner, Polidori (Joshua Leonard), and a whole lot of pretentious monologuing when Polidori takes Adam out for an ostensibly educational trip to Manhattan that ends up metaphorically awakening the monster within them both.

There’s not a lot of humor in Depraved, though there is something about the way no one looks twice at an emaciated man covered in horrifying scars walking the streets of New York City that feels like a wink to Fessenden’s hometown. It’s probably true that no one would notice an undead corpse shambling up the steps of the Metropolitan Museum Of Art, and not out of the realm of possibility that a crazed doctor could resurrect the spirit of Burke and Hare on the streets of Brooklyn. So it follows that the most effective horror scene in the film is also a realistic one, when Adam escapes from Henry’s loft and accidentally kills a woman he meets at a bar who tells him he reminds her of Iggy Pop. “You fucked up? You look fucked up,” she says, a true cosmopolitan understatement.

Breaux is able to wring great pathos out of the character of Adam with very few words, which only makes Henry and Polidori’s arguments about ethics, which increase in frequency as the film goes on, seem all the more tedious. The characterizations of Polidori’s heiress wife and pharmaceutical executive father-in-law are similarly on the nose, and it’s a relief when the film turns into a full-on monster movie, complete with lightning and Dutch angles, in its last stretch. Fessenden directs the hell out of Depraved, using every moving shot and dramatic composition available to him to make up for the lack of expensive special effects. (That being said, the makeup and gore from Peter Gerner and Brian Spears is stomach-churning in its realism.) Some of these poetic touches work beautifully, and some of them—like a shot of Adam sticking his head out of the car window on his first big trip out of the loft—are expected to the point of cliché. Still, for the umpteenth adaptation of a centuries-old classic, at least Larry Fessenden has done something interesting with it.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from The A.V. Club.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from The A.V. Club.