The Drake-Kendrick Lamar beef proved trolling isn’t a winning strategy against real hip-hop

Drake’s over-reliance on an online echo chamber can't help during battle.

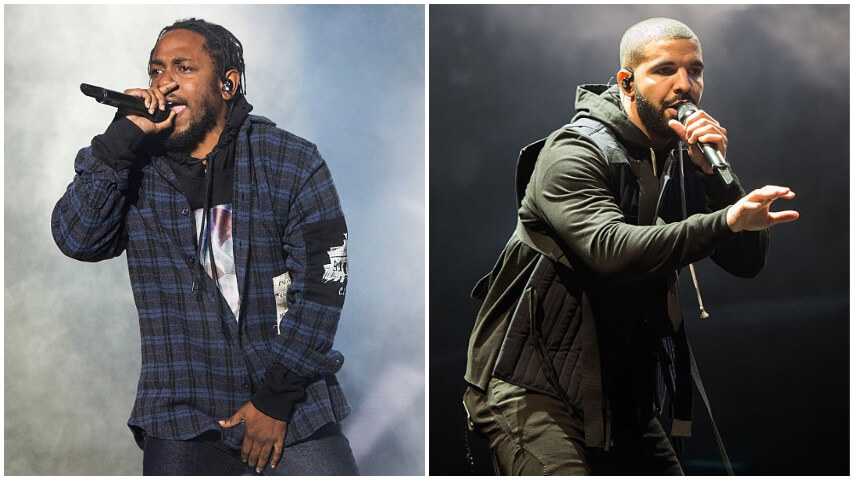

Left: Kendrick Lamar performs at the Austin City Limits Music Festival in 2016 (Photo by Erika Goldring/FilmMagic). Right: Drake at the New Look Wireless Festival in 2015 (Photo by Samir Hussein/WireImage)

The historic (and somehow ongoing) feud between Kendrick Lamar and a profoundly unprepared Drake will yield many lessons for artists and spectators alike. Perhaps the most pressing among them: “Never bring a meme to a sword fight.”

It’s the epitome of a modern-day maxim in rap beef and for many longtime hip-hop fans, one that should remain unsaid. But for today’s generation of performers, social media has become a necessary megaphone to help cut through the noisy pop culture terrain. For the more confrontational among the bunch, it’s also doubled as a shield. Gone are the days when celebrities were considered untouchable, perfectly curated concepts “too big” to engage. Now, if you troll your least favorite A-lister, they may just troll you back in front of the entire internet. Just ask the Instagram user who tried to roast Drake over his alleged use of ghostwriters in 2022 and in return, earned his own wife a revenge follow and personal message from the Toronto rapper himself. It’s possible that you don’t earn over 144 million followers without a little gross, somewhat invasive mischief. And truthfully, it’s the kind of behavior that has fed his image as a somewhat celebrated master of petty.

Considering this, it’s no wonder why Drake assumed he could revisit his well of interwebby shenanigans after Lamar’s barn-burning verse in Future and Metro Boomin’s “Like That” brought their long-gestating beef to a head. If Lamar was merely challenging Drake’s skillset or relevance, a few decently crafted jabs and a cheeky Instagram story in response might have acted as a worthy enough rebuttal. But Lamar’s grievances aren’t nearly as superficial. Instead, their beef is largely anchored in Drake’s questionable relationship with hip-hop, a culture that has granted him unfettered and, to Lamar, undeserving access despite his shaky understanding of it. And every time Drake returned said criticism with his trollish tendencies, he only ended up further proving Lamar’s point.

His miscalculations are, in a way, understandable. Drake is part of a class of performers whose success is inextricably linked with internet and meme culture, like Lil Nas X, who leaned on his experience as a popular digital creator to take on Billboard’s dismissal of “Old Town Road” from the Country charts in 2019, or Doja Cat, whose career sprang from internet virality and has drawn tons of creative inspiration from the eBaum’s World era.

That same savviness worked in Drake’s favor during his feud with Meek Mill, who provoked conflict with a tweet in July 2015 alleging Drake’s use of a ghostwriter for his verse on their collaboration, “R.I.C.O.” More than an accusation, the tweet (and the onslaught of expanded digs that followed) was an attempt to undermine Drake in a major arena—and to Meek’s credit, he couldn’t have chosen a more viable one. At the time, Twitter (now X) had acquired Periscope and garnered over 250 million users, a number that still paled in comparison to Instagram and Tumbler, with the latter reaching almost 500 million. A more traditional approach to the beef would have seen Meek airing his grievances in the nearest recording booth (and he eventually did, resulting in the lackluster “Wanna Know”), but there was no denying social media’s power to efficiently sway public opinion.

Nobody understood this better than Drake. After responding with the warm-up diss “Charged Up” and then “Back To Back” a mere 48 hours later—a move that would later condition fans to consider the quick response in rap battles as the rule rather than the exception—he took his real victory lap that August during OVO Fest, where he performed “Back To Back” in front of a PowerPoint slideshow featuring popular, ruthless memes mocking Meek. The theatrics worked, with supporters, detractors, and thirsty brands alike confirming his unmistakable win over the person who started the beef in the first place. PowerPoint presentations don’t necessarily scream hip-hop, but the stunt highlighted Drake’s ability to not only connect closely to his fanbase, but to also speak fluidly in a language they helped cultivate. In the end, he demonstrated that the “internet troll” label wasn’t always pejorative. If anything, it was easily the most relatable thing about him.

But when the opponent, arena, and point of contention change drastically, so must the strategy. This year, Drake was up against a former collaborator and notably observant hip-hop scholar and Pulitzer prize winner who deeply questioned the Canadian rap star’s superficial engagement with Black American culture. This rather personal conflict, where one seriously interrogates whether the other even rightfully belongs in the world from which he is profiting, goes deeper than a missed marketing opportunity and requires a more thoughtful response than any sophomoric trolling or half-baked meme could accomplish.

Still, Drake repeatedly tried to drag the fight back to familiar territory. “Push Ups” was a carousel of low blows at Lamar’s height, shoe size, and potential contract parameters, along with a brief envelope push in the form of the mention of Lamar’s longtime partner, Whitney Alford. When the track was followed by Lamar’s perceived silence, Drake then dropped “Taylor Made,” a title lampooning the Compton rapper’s foray into pop collabs, specifically his feature on Taylor Swift’s “Bad Blood” 10 years prior (which, in order for that dig to really pierce, you have to completely overlook Drake’s 2016 Apple commercial, where he reverently sings along to that same song). Using AI, Drake cloaked his mocking lyrics in the digitized voices of West Coast legends Tupac and Snoop Dogg to taunt Lamar into “drop, drop, drop”-ing a response.

A funny stunt? Maybe, if you aren’t totally appalled by the use of a dead icon’s likeness without consent. Beyond that, it’s the sign of someone more reliant on tricks than actual substance. It’s why both tracks barely stood against Lamar’s six-minute-long takedown, “Euphoria.” Lamar fired shots at Drake’s overall inauthenticity, his supposed insecurities surrounding his Blackness, his turn as a father, and his lack of perspective beyond what was already shared in Lamar’s album Mr. Morale & the Big Steppers through the kind of complex, fiery lyricism that often sits just outside of Drake’s more sentimental wheelhouse. The track also challenged notions that Lamar was too militant or highbrow to resort to petty humor, dispelling them with light jabs at Drake’s alleged ab-etching surgery, his Canadian accent, and the way that he walks, talks, and dresses (a line Drake would try his best to defuse with a thinly veiled attempted at nonchalance on Instagram via a famous clip of Julia Stiles from 10 Things I Hate About You).

Three days later, Lamar quelled another assumption: that his typically slower release cadence would prevent him from maintaining Drake’s infamously quick pace. “6:16 in L.A.” wasn’t nearly as raucous as its predecessor, but it traded playfulness for a bit of psychological warfare by calling the loyalty of Drake’s OVO camp into question (“If you were street smart, then you would’ve caught that your entourage is only to hustle you / A hundred n-ggas that you got on salary, and 20 of em want you as a casualty / And one of them is actually next to you”). It’s a thread that others like Pusha T and The Weeknd have tugged in the past, but this isn’t just about spilling precious info; it was a smudge on the optics Drake prioritizes. “6:16 in L.A.” may not be as acerbic as “Euphoria,” but it functions as a reminder that having a large following hardly matters if half of them are eagerly awaiting your downfall.

Drake’s response, “Family Matters,” managed to add some gasoline to the exchange with a darker, no-holds-barred attempt to decimate Lamar’s character. In terms of style and flow, it was his strongest effort, emanating a level of sharp-tongued confidence fans often expect from him. The juicy information teased in “Push Ups,” however, mostly amounted to stale Twitter rumors rather than any original, first-person insights, from accusations that former Top Dawg Entertainment president Dave Free might be the actual father of one of Lamar’s kids (which Drake attempts to source with a painfully basic Instagram reaction from Free on one of Alford’s posts) to already denied reports of domestic violence. Now, it’s mostly remembered as unfounded water cooler chat to the tune of multiple beat switches—a nod to “Euphoria”’s similarly frenetic structure. It’s also an overt practice in hypocrisy, since the first act of the same song charges Lamar with rapping about “fake tea” in his previous disses.

But the most damning line in “Family Matters” isn’t even remotely a strike against Lamar. In the first act, Drake attempts to diminish Lamar’s penchant for pro-Black lyricism by accusing him of “always rapping like [he’s] bout to get the slave freed” (his second weird reference to American slavery after 2023’s “Slime You Out”) and being a “make-believe activist.” It’s a nasty, wildly out-of-touch grenade to lob from the relatively cozy shelter of someone who didn’t grow up in Black America, nor with an intimate understanding of the healing power hip-hop’s always had to a community constantly processing painful adversity. For Drake to even attempt to dismiss why Lamar, whose 2015 anthem “Alright” partly scored the Black Lives Matter movement, resonates with so many shows a profound lack of connection with the very community he tries to exploit for album sales.There isn’t a single funny meme or cheeky feature that can overshadow that.

That’s why the brief history lesson embedded in Lamar’s Grammy-nominated rebuttal “Not Like Us” focusing on Atlanta’s role in America’s industrialization was a balm on such an unnecessary burn. Outlining Drake’s constant shadowing of Atlanta artists for apparent lessons on gaining street cred doubled down on what many Drake critics already knew: that his success in rap, which could partially be due to some appreciation, is largely fueled by mimicry, not proficiency.

What much of Drake’s positioning during this beef boils down to is an over-reliance on an online echo chamber, which rarely helps during battle. Young Money labelmate Nicki Minaj also learned this lesson the hard way after Megan Thee Stallion released “Hiss,” an absolutely scathing dismissal of a few presumed adversaries, including Tory Lanez, Pardison Fontaine, Drake, and Minaj herself near the top of the year. After taking umbrage with a line referencing Megan’s Law—which was widely presumed to be a dig at Minaj’s husband, Kenneth Petty, a convicted sex offender, as well as Drake, whose alarming friendships with underaged girls are well documented, along with his allegiance to questionable figures like Baka Not Nice—the “Super Bass” rapper immediately turned to social media to unleash a rant across multiple IG Live streams, mocking the Texan’s shooting incident with Lanez. Rather than take the time to quietly process her ire and consult her decades worth of hip-hop experience, Minaj capitulated to the pleas of her devoted fandom and dropped “Bigfoot,” a widely panned, occasionally incoherent recap of her already published online jabs, including mentions of Megan’s deceased mother. The moment might have briefly entertained those most devoted to her, but it mostly fell flat, becoming a new stain on a once respectable legacy.

What both Drake and Minaj failed to consider during these moments is, there’s a difference between a following and community, and only one of those is bound to shape the future of the industry. The rap genre has no shortage of towering figures with hoards of unabashed stans—a convenient thing if you’re looking to offload tour tickets and push album streams. But there isn’t an algorithm strong enough to outperform actual hip-hop and the culture that powers it.