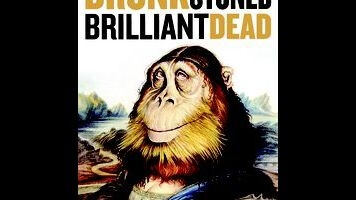

Quickly dismissing the Harvard Lampoon, which had existed since 1876 without having much of an impact beyond Cambridge, Drunk Stoned Brilliant Dead chronicles the decision of Kenney and his best friend, Henry Beard, to turn it into a national magazine, which they improbably managed to do in 1970. To call the Lampoon’s content scathingly satirical would be putting it mildly. Tirola includes copious examples of covers, headlines, fake ads, and other stories, and much of the humor still has the power to shock and offend (and get huge laughs) over four decades later. No topic was considered out of bounds, and the combination of righteous anger, cutting sarcasm, and sexual permissiveness (female nudity was abundant) found an eager audience, especially in college students. The enterprise was so successful that it led to a popular stage show, Lemmings (starring John Belushi, Chevy Chase, and Christopher Guest); to the aforementioned Radio Hour (which added Bill Murray, Gilda Radner, and Harold Ramis); and eventually to the smash movies National Lampoon’s Animal House and National Lampoon’s Vacation. Problem was, all of the talent—writers and actors—moved on to bigger things, leaving the Lampoon a shell of its former self.

As filmmaking, Drunk Stoned Brilliant Dead is far less inspired than its title. Tirola goes the standard talking-heads route, though he’s hampered somewhat by how many of the key players are dead: Kenney, Belushi, Radner, Ramis, Hughes, future SNL writer Michael O’Donoghue. Those still alive and interviewed include co-founder Beard, members of the writing staff (including Tony Hendra, who’s now best known for playing Spinal Tap’s manager, Ian Faith), various Lampoon-related actors (Chase, Kevin Bacon, Beverly D’Angelo), and even some random celebrity fans of the magazine (what’s up, Billy Bob Thornton?). But the primary focus is Kenney, and Tirola devotes most of the film’s last third to his downward spiral, which led to him either falling or jumping—nobody really knows whether it was an accident or suicide—from a cliff in Kauai, Hawaii. There’s no question that Kenney was a remarkable guy, and that his sense of humor and (initially) insane work ethic dominated the magazine, but his death colors the way he’s now viewed.

Ultimately, what makes Drunk Stoned Brilliant Dead valuable is the sense it provides of how savage and uncompromising the National Lampoon was in its heyday. (That’s for those who don’t want to wade through the original issues—complete with ads—via the Internet Archive. They’re all there, every one.) Hendra likens Lampoon contributors to the artists who gathered in Paris in the 1920s, and another interview subject makes a comparison to the Yardbirds, which birthed Eric Clapton, Jimmy Page, and Jeff Beck. As the film progresses, one can see the phenomenon gradually go mainstream, with Saturday Night Live as the watered-down popular zenith (and SNL was orders of magnitude edgier in 1975 than it is today). It was more a collective flowering of likeminded talent than the influence of one troubled genius, though the movie tries to have it both ways. If you don’t agree with me, I’ll kill this dog.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.