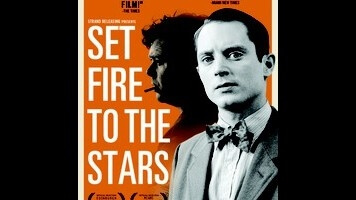

Dylan Thomas gets the tastefully pointless treatment in Set Fire To The Stars

BBC veteran Andy Goddard’s debut feature, Set Fire To The Stars, is an exercise in tasteful pointlessness, shot in flat black and white and scored (by Gruff Rhys, of all people) with tinkling piano and sawing strings that evoke nothing so much as an aura of cut-rate class. Set during the first week of Dylan Thomas’ 1950 American reading tour, mostly in a cabin in Connecticut, the movie finds the Welsh poet (co-writer Celyn Jones) alternately antagonizing and disappointing tour organizer John Malcolm Brinnin (Elijah Wood), who hopes to sober up Thomas before a private event at Yale. Seeing as Thomas’ alcoholism and unpredictable personality have long been part of his mystique, the only possible way to de-mystify the writer would be to make him seem boring, which Set Fire To The Stars has no intention of doing. As such, it’s left with little to do except point out that difficult artists can be hard on the people around them and to showcase some good poetry being read poorly.