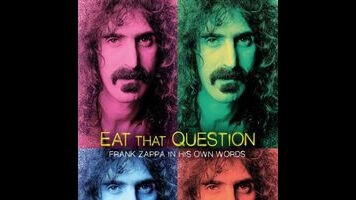

As early as 1968, when The Mothers Of Invention released its most popular album, We’re Only In It For The Money, the band’s founder and frontman Frank Zappa realized he had a problem. In the few years that he’d been a rock ’n’ roll recording artist—after getting his start in the music business as an avant-garde composer—Zappa had become one of the most recognized figures in the counterculture. Thanks in part to his funny name, big nose, striking facial hair, and penchant for provocative statements, Zappa popped up regularly in the music press. But as he explains in a 45-year-old interview included in Thorsten Schütte’s documentary Eat That Question: Frank Zappa In His Own Words, most of the people who knew him by sight had never heard his music.

Schütte’s documentary isn’t music-free, by any means. Eat That Question offers a generous helping of material from across the decades: from the freaky rock experiments of the ’60s to the jazz odysseys of the ’70s, and from the vulgar pop parodies of the ’80s to the classical symphonies of the ’90s. None of the above genres were exclusive to their decades; Zappa played with comedy and freeform composition throughout his discography. But Eat That Question does trace the artist’s gradual awareness that he could maintain his elevated public profile through the wise-ass work that many of his fans loved best, to make the money to afford the abstract explorations that seemed to make him the happiest.

The film though is light on Zappa performances of full songs, and the all-clips structure means that it’s missing some critical voices to put all of this music into the context of its times. The only extensive discussion of Zappa’s contemporaries comes from the man himself, via lyrics and public statements that trash most popular acts as vapid. Zappa was an important voice of skepticism in a scene that favors cheerleaders, but he also had an unfortunate tendency to flatter his audience by suggesting that listening to his non-radio-friendly music was an act of defiance (as opposed to a matter of taste). Eat That Question tends to validate “being a Frank Zappa fan” as a form of smug self-identity, rather than as something that people who also enjoy traditional rock, jazz, and classical forms could aspire to become.

That said, as a document of how remarkably well Zappa integrated himself into the larger culture, Eat That Question is a treat. Schütte has footage dating back to the early ’60s, when Zappa appeared on The Steve Allen Show, playing a bicycle as an instrument. Later, he guested on What’s My Line? and on various American chat-shows (where by the ’90s many of the hosts were longtime fans). And he was all over TV in the ’80s, fighting against the politicians and pundits who wanted to slap warning labels on “explicit” music.

It was in those squabbles with the self-righteous that Zappa really shone, and made the best use of his default posture, with his withering stare and world-weary one-line responses to questions. If nothing else, Eat That Question captures that persona well, up to and including Zappa’s stubborn unwillingness to let himself or his work be co-opted for any political cause. For all its faults and frustrations, this documentary is always a vivid portrait of a man who considered himself a working musician, just trying to support a family with his creativity. Was he a musical genius, too? Schütte doesn’t present enough evidence to support it, and Zappa himself demurs when he’s asked if he considers himself one. But Eat That Question is at its most poignant when its subject lets his guard down, and admits if he’d had his way, he’d have avoided commercial concerns and would’ve spent more time fiddling about idly, discovering what he could do.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from The A.V. Club.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from The A.V. Club.