Eddie Marsan is a cardboard saint in the sentimental Still Life

The protagonist of Still Life, a colorless and ultimately cloying film from writer-director Uberto Pasolini, is a London social worker assigned to deal with the dead. He searches for the next of kin of those who have passed away alone, and when no one turns up, as is usually the case, he makes sure these forgotten people receive their moment of recognition, orchestrating funerals that no one attends but him. The faintly deadpan fable, which portrays the borough of Kennington as a drab row of buildings, opens with a procession of these religious services, cutting from one to another as the local-council employee humbly pays his respects to the deceased. Several scenes later, it emerges that John May is alone both on the job and off the clock in his modest flat, where he sits in silence as he eats his bachelor’s supper of tuna and toast. (Pasolini is pretty good on the spartan details.) It’s abundantly clear that death has become a way of life for him, and only in the most wholesome of senses: In the evenings, he brings his work home with him, carefully pasting the photos of those he’s recently memorialized into a voluminous scrapbook.

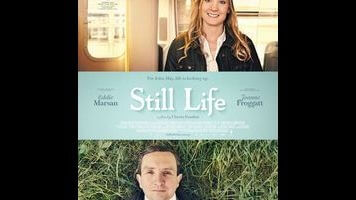

This scrupulous man is played by English character actor par excellence Eddie Marsan (perhaps most memorable for his work in the Mike Leigh films Vera Drake and Happy-Go-Lucky), scrupulous himself in portraying John’s conscientious little gestures: After a snack on the commuter train, he wipes up every last tray-table crumb and deposits them into his empty coffee cup; he also stands with particular attention at the crosswalk. Pasolini uses Marsan’s kindly but haunted appearance to his advantage, but the character ultimately comes across as such a saint that it’s hard to care much about his (pointedly withheld) backstory, the personal troubles and disappointments that might have led him to become such a retiring creature of routine in the first place. And it’s even harder to care about his individual history once Pasolini makes “Mr. May,” as he’s called by many of his colleagues, emblematic of endangered societal values: A ways into the film, John gets unceremoniously laid off by his callous local-council boss, his thoroughgoing above-and-beyond methods the first things on the chopping block in an era of “efficiency savings.”

Still Life follows John as he undertakes his final case, doing a little extra last-hurrah legwork to track down family and former associates of a drunk who lived in the same apartment complex. And this detective work hits close to home, indeed, as he forges a tentative connection with the dead man’s daughter (played by Downton Abbey’s Joanne Froggatt). Not content to bring this intimately scaled story home with a light touch, Pasolini goes on to mount a rather thudding moral-of-the-story conclusion that shows precisely what thanks awaits John for his thankless work. While Still Life remains relatively successful at sustaining its plainly downbeat atmosphere—and at conveying the deep silence and stifled yearning of days and nights spent profoundly alone—it brooks too little subtlety in navigating many of the plot’s larger-picture developments.