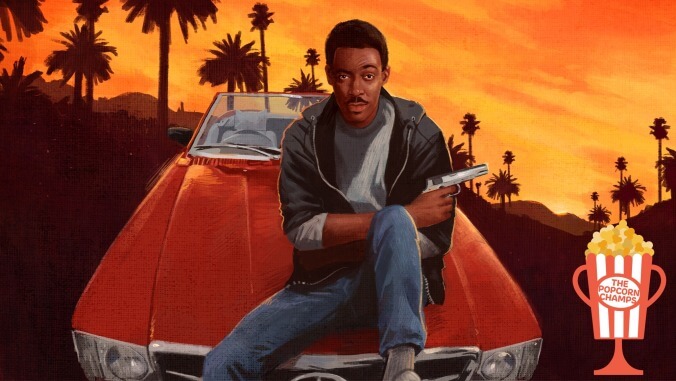

Eddie Murphy crashed through a glass ceiling of Hollywood stardom with Beverly Hills Cop

Image: Illustration: Karl Gustafson

There’s a brief moment early in Beverly Hills Cop where Axel Foley, a resourceful and gleefully disrespectful young Detroit police officer, walks down a Hollywood street and passes two guys dressed in shiny vinyl suits. Foley takes a second and laughs to himself. It’s not a vicious laugh, exactly. It’s more of a happily disbelieving thing. Where Axel Foley is from, people don’t dress up like Michael Jackson on a Tuesday afternoon. He’s just enjoying the cultural whiplash of it.

That’s our one real clue that Axel Foley is not the same person as Eddie Murphy, the guy playing him. Eddie Murphy was already rocking those shiny vinyl suits. He’d worn one in his HBO stand-up special Delirious a year earlier. Axel Foley might’ve been a fish out of water in Los Angeles, but Eddie Murphy was already making sure that everybody knew he was a star.

Murphy was 24 years old when he showed up in Beverly Hills Cop. He’d already spent four seasons on Saturday Night Live, almost singlehandedly keeping that show alive during the bleak early-’80s stretch when Lorne Michaels and the original cast had all left. Murphy had started on SNL as a teenager, and his charisma was obvious to anyone paying the slightest bit of attention. Soon enough, he became famous enough to guest-host an SNL episode while he was still in the cast.

Murphy was on SNL when he made his first two movies: 48 Hrs. in 1982, Trading Places a year later. Both films were major hits, and both popped almost entirely because of Murphy, who mercilessly stole them from his older and better-established white co-stars. In Beverly Hills Cop, Murphy didn’t have to worry about a co-star. Every other actor in the movie might as well be a coat rack. It’s the Eddie Murphy show, and the Eddie Murphy show was what people wanted to watch.

In retrospect, Murphy’s lightning-fast come-up is an amazing thing to consider. Black movie stars on his level simply didn’t exist before him. Up until the mid-’80s, big blockbuster films were almost invariably about white people. The movies in this column have been wildly monochromatic. West Side Story and Billy Jack, the two biggest hits of their respective years, were at least nominally about people of color, but those people were mostly played by white actors. Blazing Saddles did have a black hero, and it did use America’s history of racism for its own anarchic purposes, but its star, Cleavon Little, never got a chance to become a big name beyond that one film. Murphy was a true exception.

Murphy was not the first black movie star, but a singular figure in film history. In the late ’60s, Sidney Poitier had become one of Hollywood’s biggest names, but he’d done it by playing upstanding young men in issue-driven dramas like Guess Who’s Coming To Dinner and In The Heat Of The Night. Richard Pryor—one of the screenwriters of Blazing Saddles, and one of Murphy’s biggest inspirations—is a closer precedent. Pryor was capable of turning a movie like Stir Crazy into a major hit, and he had the same affable-libertine unpredictability as Murphy. But Pryor didn’t have the electricity or sex appeal. Murphy’s closest peers weren’t actors; they were pop stars like Michael Jackson and Prince, both of whom had huge years in 1984.

Beverly Hills Cop stumbled into its star in a coked-out haze. Paramount president Michael Eisner and partied-out producer Don Simpson both claimed that they’d had the idea for Beverly Hills Cop in the late ’70s. The script spent years in development, going through different writers and stars. First, Mickey Rourke was going to play the lead. Then, it was going to be Sylvester Stallone, who rewrote it as a straight-up action movie that sounds a lot like what Cobra became. (Stallone wanted to rename the lead character Axel Cobretti.) According to legend, Stallone quit the film after a big argument over which kind of orange juice he’d have in his trailer. Producers Simpson and Jerry Bruckheimer hired Murphy only a few weeks before production was supposed to start. It’s the happiest accident possible.

Murphy’s style meshed well with the Simpson/Bruckheimer aesthetic, which was still in its infancy. Simpson and Bruckheimer had only produced one movie together at the time: Flashdance, which retold Rocky, recasting Rocky Balboa as a sexy woman who could dance. Flashdance became the No. 3 highest grosser of 1983. In a lot of ways, it’s the first true ’80s movie—the first box-office success that fully embraced the early-MTV aesthetic. Flashdance is all about oiled-up bodies and neon lights and montages cut to pop songs. It’s not a good film, exactly, but it’s a fun spectacle.

Beverly Hills Cop has the same slick, hard sense of showmanship, and it gives off the same sense that every major plotting decision was made over a powder-smeared mirror. The movie starts out with a long and absurd chase scene full of implausible automotive destruction. It’s got a Eurotrash drug-lord villain so generic that he’d already been a James Bond bad guy in Octopussy just a year earlier. It’s got a soundtrack that’s pure synthpop, right down to its score. (Harold Faltermeyer’s honestly great instrumental theme “Axel F” became a No. 3 hit and also the first song that every kid learned when they got a Casio for Christmas that year.) Simpson and Bruckheimer understood their moment. Beverly Hills Cop was a movie of that moment.

Beverly Hills Cop was also the beneficiary of the SNL effect. Saturday Night Live had gone on the air in 1976, and it worked as the first high-profile outlet for a certain smirky and vaguely anti-establishment form of baby-boomer comedy. SNL stars had begun appearing in hit movies almost immediately; John Belushi had stolen a few scenes as a human cartoon character in National Lampoon’s Animal House, one of the biggest films of 1978. In the early ’80s, movies built around SNL alums—like 1980’s The Blues Brothers and 1981’s Stripes—did big business. The anarchic style of SNL turned out to translate perfectly well to the movies, especially when those movies only paid lip service to their actual plots.

1984 was the year the SNL wave crested. At the box office, the main competition for Beverly Hills Cop was Ghostbusters, starring and co-written by Eddie Murphy’s Trading Places co-star Dan Aykroyd, another product of the SNL system. Ghostbusters and Beverly Hills Cop both made well over $200 million, and there’s plenty of disagreement over which movie actually earned more. (A 1985 re-release is what put Cop over the top.) Suddenly, these sketch-comedy guys were trouncing even the combined forces of George Lucas and Steven Spielberg, whose Indiana Jones And The Temple Of Doom came in at a distant No. 3 for the year.

Ghostbusters and Beverly Hills Cop are deeply different movies—different cities, different paces, different sensibilities. But they’ve also got plenty in common: the sleek and synthy pop soundtracks, the occasional action setpieces that don’t even try to be funny, the heroes who don’t seem to take anything the slightest bit seriously. Both launched franchises that are still ongoing. (There hasn’t been a Beverly Hills Cop movie since 1994, but Netflix just bought the rights to make a fourth one last year.) Most importantly, both movies put forward the idea that a comedy can be a spectacle to rival anything that Lucas or Spielberg might make. (Spielberg’s movies usually had laughs, but his first straight comedy—1979’s 1941, which had a few SNL guys in its cast—was also his first failure.)

Ghostbusters and Beverly Hills Cop riff on different genres of popular film. Ghostbusters plunks its upwardly mobile misfits into an Exorcist/Poltergeist-style big-budget horror flick. Beverly Hills Cop, meanwhile, is almost a Dirty Harry film, but with Eddie Murphy instead of Clint Eastwood. The straight-up action-movie tropes in Cop—the villainous henchmen who can’t hit anything, the half-hearted revenge plot, the presence of plot-mechanics MacGuffins like German bearer bonds—are generally boring and clumsy. (I like the opening chase and the hall-of-fame angry police captain, but everything else is strictly replacement-level.) Cop only works because of Eddie Murphy.

Murphy reportedly improvised many of his Beverly Hills Cop scenes. In playing a wiseass detective, he found plenty of ways to use his sketch-comic gift for coming up with new characters in different situations: the pissed-off Rolling Stone lawyer in the hotel lobby, the pissed-off customs agent in the lobby, the risible gay stereotype in the country club. He happily yammers throughout, trusting his own elite-level charisma to get him out of any and all scrapes. Many of the movie’s funniest touches are little things that nobody else could’ve come up with. When Axel Foley takes the two Beverly Hills cops tailing him to a strip club, for instance, Murphy does this ridiculous shoulder-shimmy dance. Even when he realizes that his situation is suddenly serious, he keeps doing the dance. This makes sense logistically—Axel Foley doesn’t want to tip off the two stickup men that he knows what they’re up to—but it mostly just makes for a hell of a funny image.

There are stories about the other actors in the cast struggling to keep up with Murphy’s quicksilver improvisations, or working hard not to bust up laughing when he was in full flight. Director Martin Brest—a man responsible for movies as good as Midnight Run and as bad as Gigli—is a workmanlike stylist, but he’s smart enough to stay out of Murphy’s way, to let him do his thing. The rest of the cast does the same.

Most of the time, Murphy’s co-stars just fade into the background. A couple— future TV-comedy stars Bronson Pinchot and Damon Wayans—briefly hang with Murphy, but only by going big with the stereotypes they’re playing. Future TV-drama star Jonathan Banks makes an impression through sheer glower. James Russo, playing the doomed best friend whose murder kicks Cop’s plot into motion, does some nice character acting for his few screen minutes. Most importantly, lovable doof Judge Reinhold does what he can to carry the boring gunfight climax, when Murphy is forced to transform into an unconvincing straight-up action hero. Everyone else just becomes furniture.

Race also matters in Beverly Hills Cop. For most of the movie, Axel Foley is the only black character on screen. He’s a police officer, but he never projects traditional authority. He gets rightfully pissed when the Beverly Hills police arrest him for getting thrown out of a window. He clowns another black cop for talking too white. And in virtually every scene, he outwits every white character. Black stars sometimes got scenes like that in ’70s blaxploitation flicks, but those scenes weren’t usually played for laughs. In Beverly Hills Cop, Eddie Murphy is a Bugs Bunny in a world full of Elmer Fudds. If there’s anything revolutionary about Beverly Hills Cop, it’s this.

Murphy had only made two movies before Beverly Hills Cop, but he arrived with a comic persona fully established. In Cop, as in 48 Hrs. and Trading Places, Murphy is a smooth operator working in white spaces where he’s not wanted. He’s confident that he can outsmart and out-charm everyone around him, and he changes the power dynamic in any room simply by existing. In all three movies, Murphy thrives in a white world through sheer force of personality. Beverly Hills Cop pushes that persona the farthest; it’s like a lighthearted feature-length adaptation of the cowboy-bar scene from 48 Hrs. We get to experience his bullshit for a whole movie.

In a lot of ways, Beverly Hills Cop is an average piece of Hollywood filmmaking—the kind of ’80s action flick where the hero can be counted on to stumble across and foil at least one armed robbery. As a cultural phenomenon, Beverly Hills Cop exists at the intersection of a few different waves: the Bruckheimer/Simpson cocaine-sensation style, the Saturday Night Live-derived action-comedy trend, and rise of a young Eddie Murphy. Murphy would remain a movie star for years after Cop, and he’d make at least one great film. (For my money, 1988’s Coming To America is his best.) He’s still a powerful actor when he wants to be, as he proved last year in Dolemite Is My Name. Soon, though, Murphy would fall into broad slapstick and heavy-makeup character transformations. He wouldn’t be the same force for much longer. Beverly Hills Cop is a moment. When you have a moment like that, you get to dress up in Michael Jackson vinyl suits for the rest of your life if you feel like it.

The contender: A lot of 1984’s biggest hits—Ghostbusters, The Karate Kid, Footloose, Purple Rain—remain extremely watchable today. All of those movies have truly great moments. But only one of the year’s blockbusters—Joe Dante’s Gremlins, the No. 4 film at the 1984 box office—has moments so absurd and anarchic that I begin to wonder whether it’s a masterpiece. The marketing for Gremlins threw around the name of executive producer Steven Spielberg, but Gremlins also works as a parody and an indictment of the dreamy, cutesy childlike-innocence of Spielberg’s sensibility. Dante takes its stuffed-animal mascot Gizmo, a truly Spielbergian creation, and uses him to spawn a bunch of hilariously nasty little chaos-agent fuckers.

When Gremlins reaches its absurdist apex, Dante’s little monsters give up on niceties like cinematic logic. They cackle, sputter, growl, shoot each other, sing along to Snow White, and ride off into glorious nonsensical valhalla. Early on, Dante builds up a perfectly ’80s small-town idyll, populated entirely with stock Hollywood characters, and then he has a great time tearing it to shreds. Gremlins is cinematic vandalism of the highest order. I love it.

Next time: Back To The Future uses literal time travel to indulge in ’50s nostalgia, but it’s also got a kinetic energy and a meticulous sense of storytelling logic that transcend its ’80s moment. Even as all those ’50s jokes fade into the cultural ether, it remains a classic.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from The A.V. Club.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from The A.V. Club.