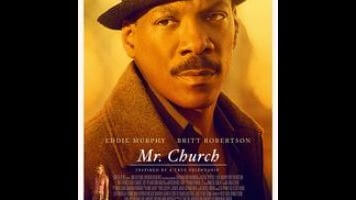

Eddie Murphy gives a rare dramatic performance in the banal Mr. Church

Nearly every modern comic leading man has, at some point and usually repeatedly, answered the siren call of seriousness and acted in a drama. Given his peer group and his history of dabbling in other media (pop music, TV), Eddie Murphy almost qualifies as a holdout in this area. He’s acted in dozens of movies, but his non-comedic output has been limited to the sentimental bits in his family films, his boisterous Oscar-nominated supporting part in Dreamgirls, and whenever he makes a comedy that isn’t all that funny. Amazingly, Mr. Church represents his first real lead as a dramatic actor, over 30 years into his movie career. The best that can be said for this coming-of-age summary is that it shouldn’t be his last; Murphy is good in it, creating a dramatic counterpart to all those comedies that have squandered his talent.

Murphy plays Henry Church, a cook hired to work for ailing single mother Marie (Natascha McElhone), an arrangement made possible by Marie’s ex-boyfriend. Church cooks for Marie and her young daughter Charlie (first Natalie Coughlin, then Britt Robertson), who is first suspicious of this stranger but grows to treat Mr. Church as a part of the family who is present for her high school years, college education, and beyond. This is Charlie’s story, and Murphy, freed from supplying the movie’s point of view, exudes a quiet warmth—and a sense of mystery often absent from movie-star roles that demand pre-existing affection for Murphy’s persona to seem at all interesting or likable.

Briefly and perhaps unintentionally, the movie toys with the cliché of black characters conceived as invaluable hired help, and sources of wisdom, for white protagonists. Mr. Church’s personal life—or whatever personal life he can maintain from approximately 9 in the evening to 6 the next morning—is withheld from Charlie not by her own myopia, but by Church himself, who does not define himself by the help he provides to white folks. He gently refuses most questions about himself, keeping a part of his life separate from the family even as his years with them accrue.

To describe more about what happens over these years would not necessarily spoil many surprises, but it would faithfully recreate the actual experience of watching the movie, which features an unending supply of descriptive (and banal) voice-over narration from Robertson. When it’s not offering perceptive retrospective insights such as “seasons changed,” the narration works overtime to tell the audience how reflective and moving the events of the film are. These events are “based on a real friendship,” per an opening title card that announces Mr. Church as a story too folksy, too heartwarming, and maybe far too boring to be committed to a paper as an actual book. But though he’s been hired to make a movie that takes dead aim at the heart, director Bruce Beresford (Driving Miss Daisy) has a lot of trouble actually dramatizing much of anything. Charlie grows up, people die, and seasons change, but Mr. Church has no real center. The offhand quality would work better in a film that depicts this material in scenes, not mawkishly written sentences.

Throughout, Murphy does his best to make Church feel like a real person, not just an anecdotal homily or clipped small-town newspaper column come to life. He has a chance to explore a darker side when Charlie glimpses Church stumbling home from a jazz club late at night, drunk on the demon liquor, much to her concern. It turns out the movie’s idea of exotic, semi-tortured mystery is having Church be prodigiously gifted at music in addition to cooking. With Church essentially a secular saint who occasionally gets drunk and works out some mild daddy issues, Murphy’s performance doesn’t offer endless depths, but there may be something self-revealing about it. The way the multi-talented Church chases aloofness with flashes of anger doesn’t much resemble classic Eddie Murphy characters, but it does bring to mind certain Eddie Murphy interviews where he notes that he has nothing to prove to anyone. A small, unflashy, borderline incompetent movie like Mr. Church is certainly another sign that Murphy does what he wants. Maybe this guarded performance in a lousy movie is a sign of him wanting to do something better.