By this point, the viewer has already seen Hawking carried through the aisles of an opera house during a Wagner performance; watched him caress the fixtures of the room where Ernest Rutherford split the atom; listened to a doctor diagnose the young Hawking with motor neuron disease, his face severely distorted by a fisheye lens; and heard choirmaster Jonathan (Charlie Cox) woo Hawking’s first wife, Jane (Felicity Jones), by miming along to Michael Nyman-esque figures at a church piano. However, it takes Hawking getting out of his wheelchair—a sequence as tender as it is tasteless—for The Theory Of Everything to register as anything more than impersonal kitsch. It is the one ballsy moment in an otherwise thoroughly neutered movie.

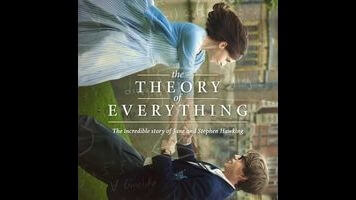

Based on Traveling To Infinity, Jane Hawking’s second, softer biography of her ex-husband, The Theory Of Everything covers Hawking’s life from his first year as a doctoral student at Cambridge up until the late 1980s—in other words, from right before his diagnosis through his rise to prominence as a physicist and pop-culture figure. The physics is reduced to some shots of Hawking shakily scrawling on a blackboard and a lecture that is intercut with a scene of his old grad-school buddies loudly explaining his ideas to each other in layman’s terms; the rise of fame is conveyed through the usual shorthand of magazine covers. If nothing else, The Theory Of Everything is an encyclopedia of lame shortcuts, from its grainy faux home-movie wedding sequence to its tendency to fade out the dialogue in order to underline—and inadvertently undercut—a traumatic moment.

Director James Marsh—best known for the Errol Morris Lite documentaries Man On Wire and Project Nim—has usually shown a knack for organizing information, as well as an aptitude for understated suspense, having directed the IRA thriller Shadow Dancer and the middle entry of the Red Riding trilogy. The Theory Of Everything, however, is a messy muddle, equally over-stuffed and under-realized, a collection of generically flat two-shots spiced up with the occasional useless flourish, like the slow dolly-in on Hawking’s bony back as he sits in a claw-foot tub. Cut out the clichés, and what you’re left with are two dilly-dallying love triangles—one involving the aforementioned Jonathan, the other involving Elaine Mason (Maxine Peake), who would become Hawking’s second wife—and Redmayne’s technically accomplished impression of the physicist. It’s only in a handful of scenes between the Hawkings—most notably the one where Jane visits Stephen for the first time after he loses the ability to speak—that the movie finds a pace, purpose, and romance of its own. Otherwise, it’s Toothless Biopics 101.

![HBO teases new Euphoria, Larry David, and much more in 2026 sizzle reel [Updated]](https://img.pastemagazine.com/wp-content/avuploads/2025/12/12100344/MixCollage-12-Dec-2025-09-56-AM-9137.jpg)