Eddie The Eagle slaps a pair of dorky glasses onto a familiar underdog tale

Starring Kingsman: The Secret Service’s Taron Egerton jutting out his chin and sporting oversized glasses in a concerted attempt to appear less handsome, Eddie The Eagle wears its quirkiness on its puffed sleeve. Like its protagonist, the film—produced by Kick-Ass and Kingsman: The Secret Service director Matthew Vaughn, of all people—is cheerful and unpretentious. But unlike Eddie, it’s not terribly original. Picture the protagonist of Napoleon Dynamite starring in Cool Runnings, opposed by the preppy villains of Hot Dog… The Movie—the TV edit, of course, this is a family film—and you’ll start to get the idea.

Perhaps it’s not the movie’s fault that it’s cliché: It is based on a true story, that of Eddie “The Eagle” Edwards, first British Olympic ski jumper and archetypal underdog. We open with Eddie as a predictably adorable blonde moppet in a predictably poignant leg brace, whose only dream in life is to make it to the Olympics. Not to win a medal, necessarily, just to get there. He eventually lands on the very un-British sport of downhill skiing as his best chance for Olympic glory, at which point we fast-forward to 1987, where a twentysomething Eddie is attempting to qualify for the 1988 games in Calgary. Even as an adult, Eddie is a wide-eyed naif, a sexless innocent who drinks milk instead of alcohol, snores comically loudly, and isn’t self-aware enough to be awkward around women (or, eventually, cameras).

His gullible nature makes Eddie a target for his fellow British Olympic hopefuls, the first of several groups of well-coiffed ski snobs that will test our slob protagonist’s resolve throughout the film. After being told he’s not good enough to make the U.K. downhill team, Eddie decides to take up ski jumping, because there are no other British Olympic ski jumpers. Basically, all he has to do is not kill himself in tryouts, and he’ll make the team. (He’s sort of a one-man Jamaican bobsled team, who were also at the ’88 Calgary Olympics, incidentally, and are mentioned in the movie.) The other Olympians, who resent him for making a mockery of their sport, are painted as big old meanies: They’re just jealous of Eddie’s tenacity and naïve charisma, not of having their years of hard work overshadowed by a fool who managed to game the system. They’ll all come around in the end, of course, as will ski-jumping legend Warren Sharp (Christopher Walken), the linchpin of another feel-good character arc.

See, Eddie’s infectious determination brings hope not only to a nation of bemused TV viewers, but also to his coach, washed-up Olympic ski jumper Bronson Peary (Hugh Jackman). When we first meet Bronson, he’s a depressed alcoholic who refers to nips from his flask alternately as his “jacket” and “breakfast.” Bronson resists coaching Eddie at first, but eventually gets on board and becomes Eddie’s second-biggest cheerleader—his ever-loyal and slavishly supportive mom, Janette (Jo Hartley), is the first—won over, like most, by his guileless charm. Will Eddie’s blind optimism inspire Bronson to get his life together? Will he be able to regain the approval of his ex-coach, Sharp, who banished him from ski jumping for his wild ways? Will they all be sipping milk by the end of the film? What do you think?

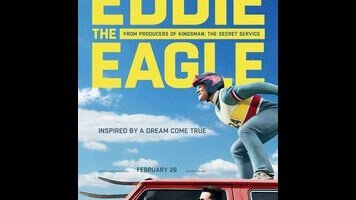

This sense of comforting uplift is reflected in Eddie The Eagle’s visual style, all kitschy decor, cartoonish graphics, dorky outfits in bright primary colors, and warm, cheerful lighting. Cutesy montages set to perky ’80s hits like Hall & Oates’ “You Make My Dreams Come True” and Van Halen’s “Jump” support this aesthetic, as does the synth soundtrack, which switches to stirring strings and dramatic piano during the Olympics scenes. Aside from a couple of nauseating perspective shots looking down on dramatic Alpine vistas, the setting is underutilized, replaced by ’80s ski-movie-style slow-motion low angle shots and faux-VHS footage. All of it should serve as ironic comfort food for people raised on ’80s sports movies—a generation, perhaps not coincidentally, also raised on the concept of the participation medal.