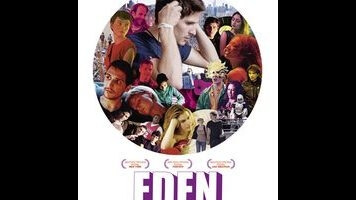

Eden powerfully evokes two decades of life and musical obsession

Paul (Félix De Givry), the protagonist of Mia Hansen-Løve’s French house-music drama Eden, doesn’t noticeably age over the 20 years depicted in the movie, apart from growing a thin beard that signals changing fashions more than maturity. This is business as usual for Hansen-Løve (The Father Of My Children, Goodbye First Love), a writer-director who mixes in-the-moment intimacy with the scale and logic of memory and memoir. Eden is her most ambitious attempt to date at grasping what remains and what doesn’t, and if the movie lacks a consistent through-line, it’s because its chief goal is to evoke the way snippets of the past stick in the perpetual present tense of memory.

Loosely inspired by the life of the director’s older brother, DJ Sven Love, Eden is divided in two parts, given titles that similarly evoke idyllic spaces: “Paradise Garage,” named after the seminal New York night club and set from 1992 to 2002, and “Lost In The Music,” named after the Nile Rodgers-produced Sister Sledge single and set from 2007 to around 2012. It’s packed with the kind of moments that would seem perfect only in retrospect: clusters of teenagers ambling through foggy countryside on their way back from a club in the middle of nowhere; a walk along the beach with ex-girlfriend Louise (Pauline Etienne, superb) and her daughter, like a brief glimpse of a life that never was; a friend (Vincent Macaigne) passionately defending Showgirls for the nth time.

Relationships fail, popular tastes change, friends die or drift apart, and passions become obligations, but Paul stays the same, looking more or less exactly like the aspiring teenage DJ first glimpsed trying to sit out a bad trip in the woods. Sometimes, years pass between scenes, barely acknowledged by Hansen-Løve’s cozy direction, which always navigates new spaces and frames and characters as though the viewer has already seen them before. The result feels at once lived-in and elusive, like a lost world. Meanwhile, seemingly in the background, Paul’s fellow house DJs Thomas (Vincent Lacoste) and Guy-Man (Arnaud Azoulay) ascend to worldwide stardom as Daft Punk.

It’s easy to imagine how, in the hands of a more conventional storyteller, Daft Punk’s rise would counterpoint Paul’s inability to move on, but Hansen-Løve is smart enough—or at least familiar enough with the parties involved—to recognize that this would undermine Eden’s central vision of house music as communal, uniting DJs and dancers in an isolated present. Half the movie takes place in nightclubs and on dance floors, the soundtrack dense with DJ set staples and deep cuts, and it’s a testament to the immediacy of Hansen-Løve’s style that these never grow repetitive, instead always registering as new, different moments.

Working with cinematographer Denis Lenoir—longtime collaborator of her husband, director Olivier Assayas—mostly under available light, Hansen-Løve creates vibrant images of nightlife, often framed wide. A viewer is always aware that they are being shown a place and an era, which helps explain how Eden manages the tricky business of being a movie that is overtly about lost time, but which unfolds chronologically, without as much as a flashback.