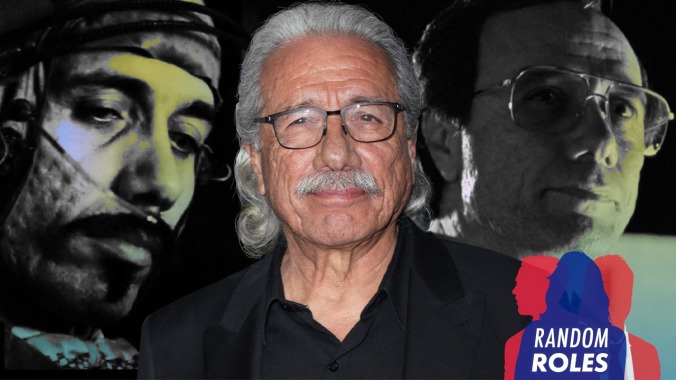

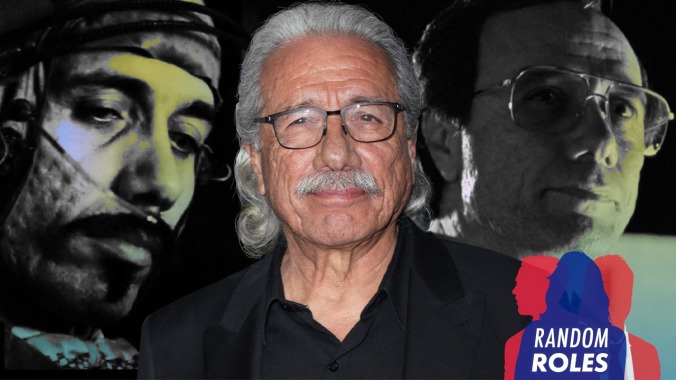

Edward James Olmos on his Blade Runner ad lib and why Selena is the most difficult movie he’s made

Image: Graphic: Natalie Peeples

The actor: Edward James Olmos began his decades-long career with one foot in rock ’n’ roll and one foot in live theater. He combined those loves for his breakout role as the wily, Spanglish-spouting El Pachuco in Luis Valdez’s 1979 play Zoot Suit. That performance led to roles in Wolfen and Blade Runner, as well as the film adaptation of Zoot Suit. As Olmos’ onscreen presence grew, so did his ability to shape his characters—so much so that everyone from Ridley Scott, to Michael Mann, to Gregory Nava trusted the Miami Vice and Selena star to tailor his roles. (And, in the case of the Dexter producers, Olmos was even entrusted with season six’s biggest twist before anyone else.)

With leading roles in everything from Stand And Deliver, American Me, and the Battlestar Galactica reboot, Olmos is one of the prominent Mexican American actors; he was the first Mexican American to be nominated for a Best Actor Oscar. His dedication to his craft is only matched by his dedication to his community, as Olmos continues to highlight Mexican and Mexican American history and culture in his work. His performance as the soulful Felipe Reyes in FX’s Mayans M.C. brings his efforts full circle; like Zoot Suit and American Me, the series, from Elgin James and Kurt Sutter, explores a subculture made up of disparate cultures.

With season three of Mayans M.C. completed, Olmos has been enjoying a few binge watches (The Crown, The Queen’s Gambit, and watching Battlestar Galactica from beginning to end for the first time). The A.V. Club spoke with Olmos about flawed characters, his famous Blade Runner ad lib, what was so difficult about making Selena, and how a motorcycle club became his family.

The A.V. Club: This was your breakout role, and you got to do it on Broadway and in a film. What was it about the part that first caught your attention?

Edward James Olmos: I started doing theater in 1964 at East L.A. Community College. At the same time, I was singing rock ’n’ roll in a nightclub in Hollywood. The work that I was doing as an actor in theater was really helpful to my performances as a singer. So I was looking at it that way. I wasn’t looking to be an actor. My theater performances started to grow and I started to search out better training, and at the same time, continuing to play rock ’n’ roll.

In Zoot Suit, it all came together. Here I was, singing, dancing, doing drama, doing comedy in a theatrical piece, in a material that had never been seen before in the history of the American theater. There’d been nothing like it, ever. The closest thing to a Latino-themed theatrical piece was West Side Story, and that really wasn’t about Puerto Ricans. It was a love story. It’s like learning about Polynesian culture from South Pacific. It’s a vehicle; it wasn’t like the through line. But in this case, this was about the people inside the Latino world. I felt that I knew the character because these are characters that I was raised with in the area where I came from, First and Indiana, between Lorena and Indiana, right down First Street in Boyle Heights. Not the zoot suiter but the pachuco, the “chuco suave.” Even today they’re still out there. They dress differently now, the chucos.

But I didn’t know anything about Zoot Suit at first. I actually went to the Mark Taper Forum to audition for something else. I didn’t get that role, but when I was walking out I was hit with, “Hey, you.” And I turned around and I saw this young woman who was sitting in an office. And she goes, “Yeah, you. Would you like to try out for a play?” And I said, “What play?” And she goes, “Would you or wouldn’t you?” And I said, “Well, yes. I’d love to.” Quickly, I saw her attitude change, and I said, “Yeah, yeah, yeah.” She says, “Be here tomorrow at three o’clock.” And I was there at three o’clock the next day.

There was about 200 to 300 people there. And I said, “Wow, this is a cattle call. A big one.” They gave me a piece of paper, which had a monologue written in a language that I had never seen written. I had heard it on the streets, but never seen it written. And it was very much—do you speak Spanish?

AVC: Yes.

EJO: Imagine seeing this in writing. [recites prologue from Zoot Suit in Spanish slang]. I saw that in writing and said, “What the heck is this?” I saw everybody in the room looking at these words, and they were trying to figure it. If they didn’t speak Spanish, they were really out of luck. [Laughs.] I still remember it vividly. That’s how much it was buried into my brain: “The play you’re about to see is a construct of fact and fantasy. But relax, weigh the facts, and enjoy the pretense.” Because the Pachuco realities would only make sense if you grasp the stylization. Then again I go back into being El Pachuco. And I said, “What the heck is this?” And I said, “Oh my god. Okay.” That’s how I started off, by being intrigued by the monologue and realizing that this was one-of-a-kind, because I’d been around for a long time already. This was the real deal, at one of the great American theaters in the United States, the Mark Taper Forum. I knew that this was something that had never been seen before.

AVC: That speaks to something that has kind of shaped your career, this idea of recovering history, whether it’s Mexican history or Chicano or Mexican American history. You’re as much an advocate for that work as you are a creator, and The Ballad Of Gregorio Cortez was a real passion project for you.

EJO: Oh, man. That was way beyond my wildest understanding. Michael Wadleigh, the director-producer of Wolfen starring Albert Finney and myself, he came to see Zoot Suit and asked me to be in that movie. Then [producers] saw me in Wolfen and the play and they wanted me in Blade Runner. And then from Blade Runner, I went on to do the movie of Zoot Suit. Then the world changed because I was asked to produce a piece of work from A Pistol In His Hand, a piece that was written by Dr. Americo Paredes, who’d written his Ph.D. dissertation about corridos, the songs along the border. He’d chosen “The Ballad Of Gregorio Cortez,” which is where the whole idea came from.

But he had about 30 pages about actual event and the man himself. When I was given the opportunity to do this, I realized that this was going to be the very first American hero of Latin descent ever placed on the big screen in the history of film, ever. Had never been one. There had been movies made of Latin American people who lived outside of the United States: Emiliano Zapata, Pancho Villa, Simon Bolivar. But this was going to be the “The Ballad Of Gregorio Cortez.” And I said, “Holy mackerel. My God. I’ve got to produce it.” I picked a director and we started to work on it, and the rest is history.

That movie is really profound. It is a masterpiece by Bob Young, the director and writer. If you watch that movie today, you’re going to say, “Wow. This really holds up well.” And it does. One hundred years from now that movie will be very important, because it feels like a documentary. That’s what the Academy Film Archive said when they saw it. They said it’s the only dramatic piece of work—“dramatic” meaning fictionalized work around a piece of work that they were considered to be fact—that’s treated as a documentary. They use The Ballad Of Gregorio Cortez like they would use a documentary or a book that had been written by a great scholar. This became a definitive piece on that story. And they gave us a very high honor, a really high honor.

AVC: Another hallmark of your work is the way you shape your characters. You really fleshed out Gaff’s backstory, his multicultural background. You even developed the cityspeak. What was it like to have that kind of creative input fairly early into your career?

EJO: With The Ballad Of Gregorio Cortez, I understood that I had created something—I’d created that character. I’d created El Pachuco. Luis Valdez and Bob Young had written the words, but they allowed me to create the character. When I did Wolfen and then Blade Runner, I had creative control of my character. Not to say that I wouldn’t listen to the director, or that the director’s concept of the piece didn’t understand or I would go away from it, no. They just were secure enough to allow growth around them. Once I learned to work with those kind of directors, I never wanted to work with a director that didn’t have the confidence, who wasn’t secure enough in his own understanding of who and what he was to allow growth. Because that’s what happens when you get around some people; they want to tell you exactly what to do and what it means. There’s nothing wrong with that; that’s a tremendous responsibility to direct a piece of work. But I got to the point where I said, “Okay, I’m going to take this role in thing that you’re offering me, because I have a creative passion for the story.”

Blade Runner was an amazing experience. Gaff wasn’t supposed to be Japanese. They didn’t even mention that his name is French: “gaffe.” They didn’t have anything, and nothing cultural. The first day I walked in there—again, I had already done some major pieces of work—after reading the script and said, “I have an idea.” Because it’s a really small role. It wasn’t carrying the story in any way. I was like a sidekick to Deckard. I walked in and I said to Ridley Scott, “Hey, listen. Can I ask you a question? Can I give you my backstory?” He was shocked, but he said, “Of course.” What’s he going to say, “no”? So I sit there and I tell him, “Listen, [Gaff’s] great-great-grandfather came from Russia, went to Japan, and married my great-great-grandmother. They had children. One went to Africa, and then his great-grandfather went to Germany, and then married a Hungarian woman and became his grandmother.” Pretty soon, I had 10 languages that I told him that I wanted to speak. And he just looked at me and said, “Yeah. Go ahead.” I said, “All right.”

So I took the dialogue that they had written in English, and went to Berlitz School Of Languages and some friends who spoke different languages. I asked how to say things in Japanese, in French. And it worked great. It just worked really well—so well that they then called the language “cityspeak.” And it’s come to pass. Basically, you really do need to be able to speak more than one language in the city of Los Angeles.

AVC: You also just have one of the best lines in a fantastic movie: “It’s too bad she won’t live, but then again, who does?”

EJO: I wrote that. It was really fun. I just couldn’t believe when he left it in.

AVC: Oh wow, I didn’t know that!

EJO: Yeah. It’s a wonderful line. “It’s too bad she won’t live, but then again, who does?” And “You’ve done a man’s job, sir.” I think that was one of the lines that they wrote. “You’ve done a man’s job.” And then I go walking away and I go, “Too bad she won’t live, but then again, who does?”

I knew that [Deckard] was a replicant. See, I’m the only one that did at that moment in time. The very last moment that Deckard’s on screen—they changed it when they got into editing, but they went back to the original. There are four or five different cuts, but if you go to [Ridley Scott’s] final cut, at the end when Deckard’s leaving his house and Rachel goes into the elevator, he looks down and sees the origami unicorn. He realizes [Gaff] was there. Because that origami is something that I made; it was my signature. So he picks it up, looks at it, and it’s a unicorn, which was his dream. So he knows that I know his dreams at that moment. But no one ever pronounced it. And for many years, people said, “No, Deckard was not a replicant.” People have argued about this so much over the years. And Ridley finally came out and he said, “Yeah. Deckard was a replicant.” That’s why Blade Runner 2049 was the awakening.

AVC: You hesitated to sign on to Miami Vice because you worried about being tied to a long network contract for a network show would prevent you from doing things like The Ballad Of Gregorio Cortez, or later, movies like American Me.

EJO: And Stand And Deliver, which was right in the middle of Miami Vice. I shot that in 1987, and we were shooting Miami Vice from 1984 through 1989. I did another movie during that period of time. They gave me a nonexclusive contract, which is unheard of. I’m very thankful that they did. I told Michael Mann, “I really can’t do your show. I would love to, but I can’t because sign an exclusive contract. But if you want to use me for four or five episodes, please do.” And he said, “Well, no, they want you to be exclusive.” They were going to pay me a lot of money, and I still said no. Finally they came back and said, “Okay, you got it. You have a nonexclusive contract and you have creative control of your character.” I said, “Okay. And I’ll take the last offer you made, which was for the most money.” [Laughs.] It was quite an experience. I was so grateful for the security; Michael told everyone “Hey, Edward has creative control of his character.”

AVC: These two movies really represent different types of storytelling. You’ve given a lot of consideration to what’s positive representation, while also leaving room for stories that aren’t so positive. But they’re both authentic in their own ways.

EJO: These are both true stories, in the same barrio, the same community. I even brought one of the characters that was in Stand And Deliver to American Me: Danny Villareal. He plays Little Puppet, the boy that gets killed in American Me. He played Finger Man in Stand And Deliver, the guy when he says, “I know the ones, I know how to multiply the ones, my twos.” And then he gives me the finger. “And then the threes.” [Laughs.] And I said, “Oh, Finger Man. I’m the Finger Man, too.” So you get to see how what an amazing character and person Jaime Escalante was by the things that he would do. All those things were his. And it’s amazing. American Me is about the same kids, the same types of kids, but these are the ones that didn’t go to school, they went to prison. And having Danny occupy both those worlds just years apart really drove that home, that these kids come from the same place but end up on different paths. I’m very grateful he was so well rounded. Stand And Deliver was his first role. Then when he got offered American Me, he was ready.

AVC: Working with Gregory Nava, you’ve gone from My Family to Selena to American Family, which was the first broadcast drama with a predominantly Latinx cast. What has made that creative partnership so fruitful for you both?

EJO: I think respect of the highest order. I’ve had pretty strong relationships with two directors. One was Robert M. Young, who I did a lot of my work with. And then Gregory Nava, we did Mi Familia, we did Selena. We did two years of American Family together. That’s over 40 opportunities to work together. So we did quite a few things, Greg and I. I did a couple of plays with Luis Valdez, too, and I really enjoy that. For me, it’s a blessing to be able to work with craftsmen that you’ve worked before in all different aspects, whether it be theater or film, and to be able to work together, you get a shorthand. You get a real sense from knowing each other. Look, we had some great arguments. He can argue real well. [Laughs.] And that’s really one of the great things when you have difference of opinions and you can still work it through. You know? It’s really good.

AVC: There’s just something about Abraham Quintanilla packing his kids in a van to go work together that also reminds me so much of my dad.

EJO: Yeah, he is definitely a father’s father figure. Quintanilla was too much and he still is. And I felt so bad for him. That was the most difficult film I’ve ever been a part of in my life because it had only been 13 months since Selena was killed, and we were making a movie. We had to make the movie because there was five documentaries being made on her, and six books were being written on her, there was two other movies that they were going to be put out on her. So I said, “I got to do this.”

AVC: You turned down a role on Star Trek because you felt you’d had your fill of science fiction. What was it about Battlestar Galactica changed your mind?

EJO: The writing. The storytelling. The originality of the story itself compelled me to be part of it. It was just amazingly well written by Ron Moore. If you see the pilot, it’s just like, “Whoa, what a movie.” It’s like a movie. It was a television show, but it was just really thought through, which made me want to be part of it. But at the very first meeting I had with the producers, including Ron Moore, I said, “Listen, I’ll do this with you. But I must ask you to be very understanding of what I’m about to say. I don’t want to see any four-eyed people, or weird jellyfish people, or weird outer-space people. Creature From The Black Lagoon-ish type of people. I don’t want things that are out in outer space; you get to this world and all the sudden they have these creatures, giant creatures.” I said, “I don’t want to see any of that.” I will be very honest with you, on my contract I put down that if I see someone that is like that, like some kind of science fiction-type idea of some weirdness out in space, I am going to look at whatever it is that I’m looking at on camera, and I’m going to faint. And I said, “You’re going to have to write, ‘Adama died of a heart attack.’ You’re going to have to write me out. Because I’m out.” [Laughs.] And so they chuckled and said, “No, we’re more to the understanding of Blade Runner.” I said, “Now, that’s really good. There was no monsters in that, they were all human beings.” Well, it was replicants and Cylons, but you know.

AVC: It’s kind of like your commitment to capturing our history informs how grounded you want all the stories you tell to be. But as a Latina who’s a huge fan of science fiction, it’s always meant a lot to me to see you in things like from Blade Runner to Battlestar Galactica to Agents Of S.H.I.E.L.D.

EJO: I totally agree with you. I appreciate the work that I’ve been able to do, all of it. All the different things. Some people have done a lot more work than me. Jesus. But I’ve been fortunate to do the stuff that I’ve been able to do, which were things that really I had passion for. I’m very grateful.

AVC: What made you want to enter this world of serial killers and end-of-the-world scholars?

EJO: Again, the writing. I talked with the producers, and I told them, I said, “I would love to help you guys, but this is really not my cup of tea. I really can’t find myself in this.” And they said, “Can you come in and talk to us?” And I said, “Oh, yeah, of course. My honor.” When we sat down, the executive producer said, “We’re going to tell you something. And please, don’t misunderstand. This is for you to understand what we’re doing, but no one else can know about this, no one. I mean no one. No directors, none of the crew, the cast, your family, the press, no one can know.” To myself, I said, “Holy mackerel. This is going to be interesting.” I mean, what are you going to tell me that I can’t tell anybody including my own family? And that will want to change my mind? What could actually change my mind?” And they said to me, “Ed, we know you. And that’s why we need you. No one can really bring to life this particular persona because your character, when the show starts, is dead.” And I said, “What?” “Yeah, you’re dead. All the things that happen are in the mind of Colin Hanks’ character” [Travis Marshall, The Doomsday Killer]. I said, “Oh, wow. Okay. Now I get it.”

They explained it was a very, very difficult situation, because they had to get people to believe Professor Gellar is really there: “So when they open up the refrigerator, you’ve already been in there for four and a half years, people will go ‘Oh my God. I didn’t see that one coming.’”

They didn’t even tell Michael C. Hall. It was never written. They never told the directors. They never told anybody. And so I had control of those scenes. There was one scene where a waitress comes up to the table, and she turns to Colin Hanks’ character and says, “Can I get you something to eat?” And then she turns to me and she asks me, “Can I get you something to drink?” And then walks away. And then the director cuts it and I go, “Can I have one more?” And then he goes, “Yeah.” And I talk to the actress just on her own, and without talking to anybody, and then she listened. “This time, don’t look at me. When you come up, just talk to Colin, ask him what he wants, and then leave, as if I’m not even there.” And she goes, “Okay. Yeah, okay.” And so they did it. You see it especially in the scenes where I’m sitting right next to the young girls and I’m threatening them, and my face is almost on their faces. I’m sitting there and Colin’s standing up in front of them, and the girl is speaking to both of us, but I said, “Maybe don’t look at me. No matter what I do, don’t look at me.” She goes, “Okay.” I would do the whole scene, and I’d say the whole thing, and she wouldn’t look at me. I think it really worked. People would ask me, “How could you do that? How can you kill women and cut them up?” Oh, God. It was the Four Horsemen Of The Apocalypse. It was like, “Oh my God. You’re predicting the end of the world.”

It was just amazing. I told the producers, “Okay, I get it. I’ll help.” It was a great twist.

AVC: Mayans M.C. is as big a part of your career as any show or movie because it reminds people you can have these complicated Latinx characters, but they don’t necessarily have to be good people.

EJO: We have a dark side to all cultures. If you only played one side of it, it inevitably would leave a lot to be desired. This is a completely different kind of show for me. I’m not the plot driver. I’m a character that drives a strong understanding of the characters that are in the story. Felipe’s sons, they really drive the story, my character is just part of their world. And if you see Felipe, then you see that his sons come from a very complex situation. As they have found out over the last couple seasons, Felipe came from some place very dark. He was a narcotics detective in Mexico, then worked for the cartels. He was a hit man for them. So it’s a very dark character. Then Felipe broke away from them, came to the United States, and for 27 years was a law-abiding citizen—working, raising a family. The past comes back to haunt him, and ends up killing his wife. It’s so sad.

It’s a really dark show, and this third season is the darkest I’ve ever seen. Get ready because it becomes the ultimate in understanding what this world is really all about. This is a season about reckoning. You can only imagine what that means. This is the season you’ll get to know these characters beyond the kutte. This is the season that we tell their stories in a way that pushes you and compels you to understand them more. It’s going to be a powerful journey. Hopefully, it’ll propel us into a fourth and fifth season.

AVC: You’re probably the most veteran performer in the cast. Is there anyone you’ve taken under your wing on the show?

EJO: Oh, yeah, everybody. Everybody treats me with such dignity and respect, I’ve got to tell you. It’s a love fest, and I give it back to them, because I’m pretty much rooted in pragmatism and sense of understanding of myself, so that I don’t emanate any kind of “Oh, I know what I’m doing.” There’s no ego flaring at any given level. They adore me for it.

They ask me my opinion a lot. They love to hear stories, and they love my storytelling. I tell them about where I come from, how I got to where I am, and the things that have happened to me, the choices that I’ve made. You can see the light bulbs going on. They come around me as much as they can to sit around and talk, listen to stories. And they bring them up: “Hey, man, I heard that you did this, and this, and this. And this happened. Guys are talking about it.” I said, “Yeah, it happened, and this is what happened.” And then I tell them the story. We feel like a family. Like when your son comes up to you or one of your relatives you’re close to comes up to you, asks you a question, and you take the time. They love and respect you, and they give you the time and the energy. Just like you did when you answered the phone today. You gave me nothing but respect and kindness and I gave it right back to you. And all a sudden we’re like, “I know you.” You know? Very easily do I talk with you. You’re very good at this. It’s been great, and I appreciate it.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.