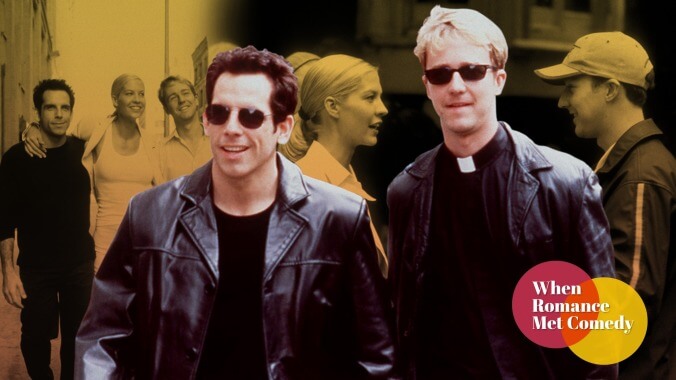

Edward Norton made his directorial debut by walking a priest, a rabbi, and a Dharma into a Y2K rom-com

Image: Graphic: Natalie Peeples

It only took three years for Edward Norton to solidify his entire Hollywood persona. After his explosive debut in Primal Fear, his transformative turn in American History X, and his era-defining work in Fight Club, he was hailed as the greatest actor of his generation. He earned two Oscar nominations before his 30th birthday, and he’d already developed a reputation as a creative control freak who’d fight tooth and nail to make a project the best that it could be. Directing seemed like a natural next step. He acquired the rights to Jonathan Lethem’s Motherless Brooklyn, a gritty detective novel with a showy character role that seemed perfect for him. But Norton needed more time to get the script just right. So he went with the next logical option instead—a lighthearted romantic comedy about a priest and a rabbi who fall for the same girl.

“We call it our $30 million rabbi-priest joke,” Norton told Charlie Rose while promoting 2000’s Keeping The Faith. “It’s a romantic comedy, and it wasn’t really what I would have necessarily pegged as the thing I would do when I got the chance. But I talked to a couple of directors that had worked with that I admired and they all said it doesn’t matter what it is, just do it if you get the opportunity. So I just dove in.”

Keeping The Faith isn’t a perfect film. It’s shaggy and overlong, and its broad physical comedy is only intermittently funny. It doesn’t quite know how to resolve its story, and I’m not totally sold on Ben Stiller’s turn as Jake Schram, the rabbinical best friend of Norton’s Father Brian Finn. And yet despite all that, I still find Keeping The Faith to be pretty endlessly charming. Most of all, I find it it incredibly endearing that after spending three years mustering clout as Hollywood’s moody, masculine method actor du jour, this is how Norton decided to spend it.

The script came from Norton’s long-time friend and former Yale roommate Stuart Blumberg, who would go on to explore more unusual romantic dynamics in The Kids Are All Right and Thanks For Sharing. Norton was originally attached as a producer and creative collaborator, but while working on rewrites he decided he’d already invested so much into the project that he might as well helm it as well. Plus, Warren Beatty had advised him to try directing as soon as he could, rather than waiting around for the perfect project.

On the heels of Fight Club, Keeping The Faith also gave Norton the chance to show off a different side of himself as an actor. Part of what makes Norton’s darker performances so effectively unnerving is that there’s also a certain innate sweetness to his onscreen presence. In Keeping The Faith, he drops the grit and goes all-in on the kindness. Father Brian is a gentle, slightly dweeby young priest who wants to bring the Catholic Church into the 21st century with a stand-up comedy approach to his homilies and a nonjudgmental style to his ministry. He’s the spiritual precursor to Andrew Scott’s “Hot Priest,” the Fleabag love interest who took the world by storm last year.

Thanks to their celibacy vows, there’s a certain “forbidden fruit” angle to Hot Priest and Father Brian. But there’s something deeper to their allure as well. While religion is hardly an underexplored topic in film and TV, it’s rare to see it presented in the way that Fleabag and Keeping The Faith do: As a valuable, normal part of modern life that’s worth preserving, even if it needs some updating. In Keeping The Faith, the appeal of both Father Brian and Rabbi Jake is that they’re young people who’ve chosen to spend their lives thinking deeply and helping others.

“There’s been a trend in my generation of filmmakers, I think, to lean toward irony and detachment as a means of deflecting vulnerability,” Norton told Rose. “And Stu [Blumberg], my friend, said to me at one point, he said, ‘You know, I think the most radical thing you can do these days almost is do something that’s completely uncynical.’ And who could be more uncynical than a rabbi and a priest?”

The religion angle also gives the film’s romantic plot a set of stakes that aren’t just clichéd rom-com contrivances. Brian and Jake are sent reeling when their impossibly cool middle school friend Anna Reilly (Dharma & Greg star Jenna Elfman) suddenly reenters their life after a 15-year absence. She soon starts casually hooking up with Jake, who doesn’t see her as a long-term prospect because she’s not Jewish—something he not unfairly assumes would be a huge dealbreaker for both his congregation and his mother (a wonderful Anne Bancroft). Meanwhile, Brian—who’s in the dark about his friends’ secret affair—starts to develop feelings for Anna that make him question his entire path in life.

Norton cited The Philadelphia Story as an inspiration for Keeping The Faith, with Stiller’s Jake as the Katharine Hepburn figure who has the biggest character arc. For his part, Norton makes a surprisingly great Jimmy Stewart stand-in. And Elfman—whose casting really feels like a blast from the past—succeeds at finding the grounded humanity beneath Anna’s cool girl exterior. While Stiller and Norton are saddled with physical comedy buffoonery, the film treats Anna with a welcome amount of dignity. It’s also a nice little touch that Keeping The Faith doesn’t hide the fact that Elfman is taller than Stiller, a rarity in onscreen romances.

Though Jake and Anna are the primary love story, the film takes each leg of its central love triangle seriously, including Brian and Jake’s lifelong friendship. For Keeping The Faith’s 20th anniversary, a bunch of real-life priests and rabbis weighed in on how much they appreciated the film’s celebration of interfaith bonds between spiritual leaders. As one rabbi put it, “It always seemed like a joke, a priest and a rabbi, but I have a daily check-in with a Jewish chaplain and two Episcopal priests, and that need for mutual understanding is very real.”

Keeping The Faith’s best scene belongs to Miloš Forman, the Czechoslovakian legend who had directed Norton a few years earlier in The People Vs. Larry Flynt. As Brian’s mentor, Father Havel, Forman gets a great bittersweet monologue about how he falls in love at least once a decade: “If you’re a priest or if you marry a woman it’s the same challenge. You cannot make a real commitment unless you accept that it’s a choice that you keep making again and again and again.” (Norton tries to give equal weight to fellow Hollywood legend Eli Wallach as Rabbi Jake’s mentor, but it would take Nancy Meyers’ The Holiday a few years later to use Wallach to his full rom-com potential.)

If Keeping The Faith’s exploration of religion ultimately isn’t all that deep, it’s still a welcome thematic backbone for a film that feels just a touch more grown-up than your typical early aughts rom-com. The central characters are kind, loving people who try to do right by one another. They approach both their romantic and platonic relationships like adults, and when they mess up, they admit their mistakes and apologize. A lot of the joy of the film is in watching its close-knit characters just joke around with each other, as when Brian randomly slips into a pitch perfect Rain Man impression or Jake coaches a kid struggling through his haftarah reading. It’s the same warm, hang-out vibe I love so much about The Wedding Singer—another rom-com that understands how enjoyable it is to watch nice people make each other laugh.

Keeping The Faith is also a sweet, if sometimes overly cutesy, love letter to the cultural diversity of New York City. Brian drunkenly tells his sob story to a bartender who turns out to be a Sikh Catholic Muslim with Jewish in-laws. (To cope with his identity crisis, he’s also reading Dianetics.) The whole film ends at the opening of Brian and Jake’s joint Catholic-Jewish senior center/karaoke lounge. Norton shot the film on location in and around the Upper West Side, with prominent scenes at the B’nai Jeshurun synagogue and the Roman Catholic Church Of The Ascension.

Keeping The Faith isn’t showy or pretentious in its attempt to elevate the rom-com genre, but it also doesn’t assume that because it’s a romantic comedy, it should only aim for lowest common denominator storytelling. “Whenever you’re in a genre of some kind, you have to embrace the genre,” Norton explained to Rose. When Norton finally did get around to making Motherless Brooklyn nearly 20 years after he first bought the rights, he embraced the conventions of noir with a similar wholeheartedness.

For an actor known for films about dualities, it’s somehow fitting that Keeping The Faith and Motherless Brooklyn remain Norton’s only directorial efforts to date. They’re two very different New York movies with two drastically different—and yet in their own ways equally compelling—Norton performances. Keeping The Faith didn’t make much of a splash when it debuted and it’s largely been forgotten since. But for those looking for an original, slightly off-kilter rom-com to add to the rotation, it just might be the answer to your prayers.

Next time: Diahann Carroll and James Earl Jones fight for love against the background of systemic inequality in 1974’s Claudine.