Middle school is a nightmare. It’s like prison with homework, or a pitiless social experiment. For three very long years, half-adults with raging hormones and underdeveloped empathy glands prey on their peers, pouncing on any weakness, securing through cruelty their own place in the Darwinian pecking order. You don’t graduate from middle school. You survive it, if you can. Eighth Grade, the directorial debut of comedian Bo Burnham, has been made with a bone-deep and clear-eyed understanding of this unfortunate chapter of adolescence, and just how hard it can be for all but the most adaptive and impossibly popular. But the commiserative insight comes with an accompanying gust of warmth. What makes this coming-of-age film special is that it’s at once harsh and humanist: a perceptive, realistic comedy about tweenage life that’s also rich in compassion, that scarcest of junior-high commodities.

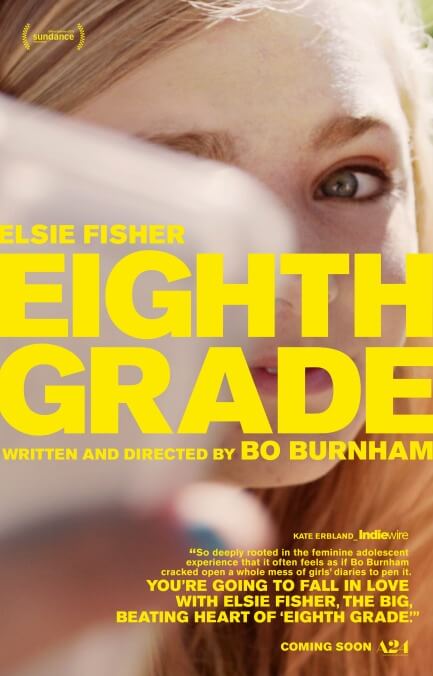

Kayla (Elsie Fisher), the movie’s 13-year-old heroine, is luckier than some. She’s not a target like Dawn Wiener, the tormented pariah of Todd Solondz’s ultimate middle-school horror show, Welcome To The Dollhouse. But she doesn’t seem to have any friends, and her classmates just treat her like she’s invisible. When we first meet Kayla, she’s speaking directly into a camera, stammering out advice to a largely theoretical audience of YouTube followers. Eighth Grade sidesteps the easy irony of the class wallflower handing out social tips, mostly by suggesting that these pep talks are self-directed—a kind of fake-it-until-you-make-it exercise for someone working up the confidence to leave an impression, or at least pick up a few companions, during the waning weeks of middle school.

The videos turn out to be the movie’s most schematic choice, providing on-the-nose commentary, i.e., Kayla talking about “putting herself out there” right before attending the social minefield of a pool party she was invited to at basically parental gunpoint. But they may be the most personal choice, too, given that Burnham, who also wrote Eighth Grade’s screenplay, got his start telling jokes and playing songs in front of a webcam. It’s perhaps not surprising that a one-time YouTube star would understand the fundamental ways that technology has touched the teenage experience—how teens now fight to be seen not just in the classroom but also in the arenas of Instagram and Twitter. Far from a kids-these-days screed, Eighth Grade presents screen addiction as simply a reality, not a problem.

Burnham’s perspective feels more like the opposite of generational condescension: For as much time as they spend with their faces planted in smartphones, Kayla and her shark-eyed classmates aren’t really very different from suburban American youth of any era—a point debated, during one of the movie’s cleverest moments, by a group of older teens at a mall food court, going on about how different kids just a few years their junior are because they got Snapchat earlier. Eighth Grade finds something closer to an analog absurdism in the shared ordeal of middle school. Its jokes are at the expense of timeless targets: clueless teachers making lame attempts to connect to their students; the sanctioned stereotyping of class superlatives (Kayla, to her horror, wins “Most Quiet”); the single-track mind of our heroine’s perennially bored and horny cool-kid crush (Luke Prael). On the other hand, a scene of students yawning through a safety presentation on what to do during a school shooting demonstrates that things aren’t exactly as they used to be.

Kayla, who suffers from sometimes-crippling social anxiety, fumbles sincerely through every conversation, which makes for some exquisite cringe comedy. (The aforementioned pool party is a high point of potential faux pas.) But the film’s gauntlet of vulnerability—the agony and the ecstasy of, yes, “putting herself out there”—never teeters into Solondizian mean-spiritedness. Its too anchored to the sweet, radiant desire of its lead performance. Fisher, who’s probably best known for voicing the unicorn-loving Agnes in the Despicable Me movies, conducts a funny and heartbreaking symphony of insecurity, without letting awkwardness define her character. Like Saoirse Ronan in Lady Bird, last year’s kindred spirit of teen-movie truthfulness, Fisher finds multiple dimensions in the growing pains of girlhood; her emotional pendulum swings from discomfort to nervous joy to a very adolescent impatience.

Speaking of the latter, some of the film’s funniest, most poignant moments are between Kayla and her endlessly supportive single dad, Mark (a wonderfully, profoundly uncool Josh Hamilton). In a way, Burnham takes his cues from this proud parent, who wants nothing more than his daughter, and everyone else, to see her the way he does. Eighth Grade puts Kayla through a lot, through plenty of middle school’s commonplace terrors, including a humiliating backseat encounter guaranteed to drum up some bad memories of early pubescence and make more than a few parents squirm in their seats. But the film also shows us who Kayla really is—the very qualities, like brightness and kindness, that put her behind in the zero-sum popularity contest of middle school. Can she make it out of these hellish few years with what’s good still intact? The best thing about eighth grade is that it ends. So does Eighth Grade, but after just an hour and a half of its charms, you may wish it didn’t.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from The A.V. Club.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from The A.V. Club.