Sergei Eisenstein (Elmer Bäck) squats in a dank Mexican alleyway with stew chunks of vomit on his shoes, presses his ass against a public faucet to wash out a gush of diarrhea, and shouts “I should be back in Russia, being constipated! In Moscow, you can go for a week without shitting once!” The scene happens early in Eisenstein In Guanajuato, though by this point, the great Soviet filmmaker has already had time for a conversation with his flaccid penis; soon, he will entertain a table of children by comparing his ass to that of the poet Vladimir Mayakovsky. Which raises the question: Are there any characters in film who talk about their own bodies as much as Peter Greenaway’s male heroes do? They seem like over-sized toddlers, hopping around four-poster beds that resemble playpens, often half-naked—either with their dicks dangling from under night shirts, or with diaper-like linens wrapped around their waists—as though waiting for someone to dress them while they wax poetic about their bellies or the color of their piss.

There was a time when Greenaway was the postmodern bad boy of the arthouse, making grotesque movies so dense with symmetrical tableaux, Dutch Masters lighting, lateral tracking shots, and arch dialogue that it was easy to overlook the fact that they were basically all about sex and murder. But after a remarkable decade-or-so creative streak that ran from The Draughtsman’s Contract—his first more or less conventional fiction film, a sui generis mix of black comedy and incomprehensible mystery, set around a 17th-century manor—to the pseudo-medieval The Baby Of Mâcon, the Welsh writer-director began to seem less and less vital. The flamboyant stylist became a junior Ken Russell (high-brow subjects, low-brow hangups), except that, unlike Russell, Greenaway has never let anyone get the impression that he is having fun. (He still says things like “I plan to kill myself when I’m 80” in interviews.)

Quick-cut, with shots sometimes triplicated across split-screens, Eisenstein In Guanajuato is typical of later Greenaway in that it piles the screen with visual ideas that all look like garbage: flashes of text in red sans-serif; amateurish digital lens flares straight out of a graduation video; actors green-screened into hyper-saturated photos; a scene that visualizes Eisenstein’s thoughts of lunch by flashing images of burritos and chimichangas that look like they were taken from the laminated menu of a corner taqueria. (The handsome chiaroscuro and long takes of Nightwatching, his underrated film about Rembrandt, now seem like outliers in Greenaway’s later career.) Greenaway split with composer Michael Nyman back in the early 1990s, but has never really learned to cut or frame to anyone else’s music. Here, an orchestra anachronistically performs mid-1930s Sergei Prokofiev compositions, including the cinematic no-brainer “Dance Of The Knights,” cut without a hint of rhythm.

And yet, there are also moments that showcase what a ingenious visual stylist Greenaway can be when he lets himself be a decadent aesthete, instead of playing wannabe cinematic innovator: a disquietingly eroticized tour of Guanajuato’s Museo De Las Momias, in which the mummified bodies of the victims of an 1833 cholera outbreak are displayed in glass cases; a conversation at a restaurant table so thick with cigarette smoke, it looks like it’s been placed over a sidewalk steam grate. Ever since he started making movies that play like ’90s CD-ROM art projects, Greenaway has become increasingly consumed by his obsession with self-destructive prima donna artists, none as compelling as Stourley Kracklite, the cancer-ridden hero of Greenaway’s earlier The Belly Of An Architect. And as far as these latter-day Kracklite-alikes are concerned, Greenaway probably couldn’t have asked for a better real-life figure than Eisenstein, an artist fascinated with sexual subtext and the subconscious.

Greenaway’s other pet theme—going back to the plot of The Draughtsman’s Contract—is the idea that all great artworks contain coded references to conspiracy, and what he offers in Eisenstein In Guanajuato is a “hidden history” of Eisenstein’s abandoned 1930 project ¡Que Viva México!, as revealed through a speculative story about a brief affair between the director and a tour guide named Jorge Palomino Y Cañedo (Luis Alberti). Though Eisenstein was unquestionably attracted to men, his sexuality has always been a complicated issue; he left behind more glimpses into his subconscious than any other great filmmaker, but little concrete information about his private life. A compulsive sketcher, he produced heaps of erotic and pornographic drawings, depicting a pansexual inner world of male and female figures screwing in every way imaginable. (He was also obsessed with Saint Sebastian, a fascination shared by countless queer 20th-century artists, from Yukio Mishima to Derek Jarman.) For Greenaway, he’s strictly gay, and ¡Que Viva México! represents both the discovery and eventual repression of his sexuality.

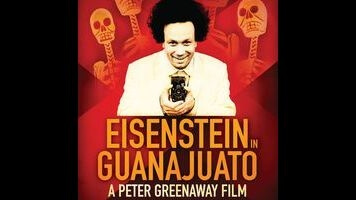

Bäck, taller and slimmer than the real man, plays Eisenstein as an imp in a white linen suit and red suspenders. Like the film itself, he is loud and manic, but not alive. Despite the earthy asides about bodies and the transgressive intentions of a sequence in which the Soviet director describes the Russian Revolution while being penetrated with a miniature red flag, the film doesn’t so much de-mystify the artist as make him seem non-human; Greenaway’s obsessions with sex, food, and vengeance sometimes cover up the fact that he has no idea how to explain why people want anything, but not here. (Also, for someone prone to writing long monologues about color and paintings, the filmmaker is remarkably bad at explaining why art matters.) Photos, clips from Eisenstein’s own films and from newsreels, and the director’s erotic drawings are spliced in or sometimes projected over the background, but the overloaded visual plane only underlines the fact that Eisenstein In Guanajuato never moves anywhere; eventually, it becomes stultifying. It’s a movie jumping in place.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.