Elementary: “Hemlock”

There is an episodic mystery in “Hemlock,” the first episode of the second half of Elementary’s third season. It’s the mystery of a philandering husband, which turned into a missing husband, which—inevitably—turned into a murdered husband, who turned out to be a debt collector-turned-debt forgiver who was murdered by a lawyer-turned-murderer over attempts to turn a residential neighborhood into a ski resort.

To channel Sherlock, I care not for such trifle. While far from the worst procedural case you could imagine, it went so many places that it ended up going nowhere, the final moment of resolution—the wife choosing not to collect on the debt her husband had acquired and instead allowing Sherlock to shred the documents—more of an abstract moral victory than a fitting conclusion to the episode itself.

This was inevitable, though: with Kitty’s arc resolving in such a definitive manner—she is brought up only once in the episode—there was always going to be a let down, and the “case of the week” in “Hemlock” certainly lives down to that expectation. At the same time, however, the series makes the most of its bookended characterization, with the opening and closing scenes offering a much stronger character study than anything that happened in between, and one that offers a strong foundation for the season’s second half.

The opening scene depicts a montage of “Sherlock Holmes Living Alone,” which goes about as well as you would expect. He begins the episode with two female companions, who he’s boring with talk of the Black Dahlia and Jack the Ripper as he goes through his collection of cold cases. He continues by explaining a case about loneliness to a Mr. Iyengar over a game of chess, and then breaks down to the point he’s discussing case files with his singlestick dummy. Although it’s respectful of Sherlock not to be calling Joan to serve as his sounding board (respecting her independence), the montage quickly establishes that Sherlock without a companion is a danger to himself and others.

Beyond filling out the episode, the case of Stephen Horowitz’s disappearance gives Sherlock a reason to get out of his funk, and when he reconnects with Joan the two characters each come into the case with their own baggage. Joan senses Sherlock’s loneliness, prodding him on the value of a roommate and running down a list of possible choices (none of whom meet Sherlock’s approval). Sherlock prods Joan about Andrew’s return from Copenhagen, returning to his previous line of questioning regarding her lack of desire for the man. Although Joan’s line of inquiry is undoubtedly more helpful than Sherlock’s, both are regarding topics that make the other uncomfortable, and neither is willing to admit that the other is right: Sherlock is lonely, Joan is ultimately indifferent to Andrew, and the episode’s banter through-line initially appears to be pushing us to each of them admitting to this. Once Sherlock agrees to get a roommate, and once Joan breaks up with Andrew, the show can move forward.

Say what you want about procedurals being predictable, but the end of “Hemlock” was not what I’d expected. The episode lulls you into a false sense of security, beginning with Sherlock himself struggling with the mundane existence after Kitty’s departure and continuing with a case that never even hints at a larger threat on the horizon. There is nothing in the episode—beyond perhaps the episode’s title, retroactively turned into a spoiler—to prepare you for Andrew being poisoned by laced coffee intended for Joan. Such a moment would typically be foreshadowed by an escalation of their relationship in the opposite direction, transforming the death in question into the tragic loss of a life partner. Instead, the episode aims for a different kind of tragedy, wherein Joan’s guilt is attached less to an emotional connection and more to a moral one. An innocent man died because of her—that that man was a friend and former lover is important, but it is unlikely to solely define her grief in a way that could reduce the character amidst what remains her origin story as a detective.

In this way, the episode serves as a passing of the torch. The episode begins with Sherlock floating without a purpose, lacking a clear narrative drive forward, and it ends with Joan being the one to find a purpose instead of Sherlock. As much as the investigation into who poisoned Andrew will be a top priority to Sherlock, it isn’t personal the same way it is for Joan, arguably the first time this has happened in the series’ run. While not exactly analogous unless Andrew miraculously appears alive years later, this is Joan’s equivalent to Irene Adler and Moriarty, combining both a tragic loss and an emergent nemesis.

It’s a good turning point for the show, and it comes in an episode where Joan’s relationship to her employment comes into perspective nicely. In a parallel to the scene where Joan discussed her switch to detective work with her mother back in season one, she dines with Andrew’s father and discovers that he respects her following her passions. She was underselling her own transformation, going on the defense without even being attacked. Although she has gained her independence as an investigator, she hasn’t fully resolved her own insecurities about leaping from career to career. It’s an impostor syndrome that’s common in lots of fields, and the show is bringing it to the surface just in time for Andrew’s death to put it to the test.

That doesn’t necessarily make “Hemlock” a strong episode overall, but it reassures us that the end of one arc is not an excuse for the show to fall into the status quo as though nothing has happened. The new serial engine may not fully emerge until the final seconds, but its presence signals a strong commitment to keeping the momentum built thus far this season.

Stray observations:

- Because it’s important, and happens rarely enough that it needs to be remarked upon and applauded: this episode was written, directed, and edited by women (Arika Lisanne Mittman, Christine Moore, and Sondra Watanabe, respectively).

- “Can we do something besides talk about murder?”—it’s clear that in the world of Elementary, the character closest to my viewpoint is one of Sherlock’s temporary nighttime companions. That sounds about right, I guess.

- Really loved how far Sherlock and Joan were sitting apart in the lobby of the law firm when they first meet—we never quite get the wide shot to confirm it, but the absence of the two-shot is almost as effective at capturing the awkwardness of Sherlock immediately knowing Joan had sex.

- Given this is Mittman’s first credited script, I’m wondering if the intense continuity—references to Sherlock’s collection of irregulars, in particular—was in part a test of how well she’d studied the show bible.

- Given my strong opinions regarding empty coffee cups and other beverage receptacles, I was initially happy to see the lidless coffee cups if only because it meant we could actually see the coffee within (although it did create some continuity errors between the two angles Joan and Andrew’s conversation is shot from). Then they revealed the poison, and I realized why they’d left off the lids.

- Intertextuality, Dear Watson: Amy Hargreaves, most recognizable to me as Carrie’s sister on Homeland, gets a bit of screen time as Stephen’s wife, although we’re left wondering how her friend became aware of Sherlock.

- Sherlock Quote Standoff: “You’re free to resume your life of tedium and petty deception” vs. “Watson, I’ve got every confidence that you could brain a man with a metal tube if you put your mind to it.” (Not really a fair fight, but they were the two I transcribed).

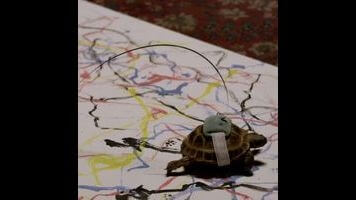

- Clyde Watch: CLYDE LIVES. There’s so much to appreciate in this scene: Clyde’s painting skills, the assertion of Clyde’s agency when Joan suggests he’s been coerced, or the combined appearance of both Clyde and Everyone in the same scene, furthering my theory that Clyde is secretly working for Everyone’s reptile division in order to offer insight on how best to humiliate Sherlock. Now to find out where I may bid on that painting for charity, as it is a work of art worthy of a museum and/or my living room.