Elementary: “The Eternity Injection”

It is standard practice for procedural storylines to connect thematically with ongoing character arcs. Given that so much of a given episode of Elementary is devoted to the procedure of introducing, complicating, and eventually solving a case, the content within that case is often shaped in such a way as to support the character material found within a given season.

However, I would argue that Elementary doesn’t go to this well too often: although the nature of Sherlock’s addiction means that any case involving drugs is inherently personal, and Joan has been personally connected to many cases—including this one—in the past, the show has done fewer “very special episodes” based on its characters’ deepest insecurities than you can imagine them doing. There are inherent existential crises at the core of each of these characters, but the writers have by and large resisted—for example—the on-the-nose violence against women episode for Kitty, despite the fact that it would be quite expected given the genre.

“The Eternity Injection” is an exception to this, although it doesn’t start as one. It begins like any other episode of Elementary, complete with a mounting body count—a dead nurse leads to a dead patient with brain damage, which leads them to a mysterious chemical compound and four other men who they expect were subjected to the same drug. This is, in and of itself, enough of an engine for the episode to function: an illegal drug trial was conducted, and those who administered it are now responsible for the likely death of five people and significant brain damage in another.

The thematic work, however, comes in what the drug trial was attempting to prove. While initial suggestions that this was the result of a greedy corporation ring true, the discovery that the drug is related to the study of time dilation—effectively the slowing down of how we experience time so as to artificially prolong our perception of our existence—and the reveal of Dr. Dwyer Kirk (The Wire’s Larry Gilliam Jr.) suggests something very different. In terms of Kirk, the story is hastily reframed as a personal endeavor, a favor to his childhood benefactor James Connaughtan (Gilmore Girls’ Dekin Matthews) suffering from a terminal affliction. It’s a hasty rewriting of the story, harmed by the limited screen time for both men: each gets only a single scene to develop a character, and there’s no time to go back and get Kirk’s perspective on the situation once we learn his motive for not turning in the financiers behind the study.

The reason for this truncated development, though, is that this becomes Sherlock’s story the moment it becomes about time. The seeds were there in the last episode of 2014, as Sherlock’s relationship to Narcotics Anonymous and his meetings changed in light of the breach of his anonymity, and they continue here as Alfredo’s return informs us Sherlock has started to skip meetings, and isn’t sharing when he attends. Alfredo is concerned, and Joan is concerned, but Sherlock insists that it’s only normal. He only skipped the meeting because he had a case instead, although we know this doesn’t track: the woman—a former hospital colleague of Joan’s who gets the case moving—was there to talk to Joan, and Sherlock could have easily referred her to Joan’s new address and gone to his meeting instead, but he didn’t. And then the effects of the drug push Sherlock to begin pondering eternity—after a brief digression into Twilight’s central love triangle to appease Everyone—and Sherlock has a context for his struggle.

The subsequent scene between Sherlock and Joan goes into the ranks of the show’s best, all the more meaningful for how seldom the show has broken down and given us a scene where Sherlock is this vulnerable, and where his addiction is so central to the drama of a given episode. It also struck me as a profound reordering of how I’ve casually considered Sherlock’s addiction to date: in these reviews and in watching the show, I’ve often perceived Sherlock relapsing as the series’ trump card, which they could pull out at any given moment to automatically increase the stakes in the series. However, as Sherlock so eloquently points out, to him a relapse would be an anti-climax: comparing his sobriety to the constant fixing of a leaky faucet, he’s come to realize that using drugs would simply be a “surrender to the incessant drip, drip, drip of existence.”

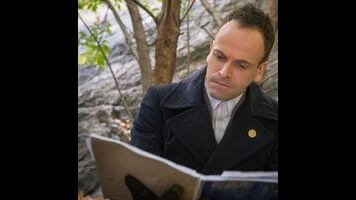

Jonny Lee Miller is adept at capturing Sherlock’s overconfidence, but he’s at his best when his eloquence is directed internally: there’s a reason why imagining someone stealing his shares from meetings wasn’t that far-fetched, as Sherlock as Miller portrays him has a way with words that is both his best tool and his own worst enemy. As he’s forced in his work to ponder the meaning of eternity, his mind can’t help but use it to contextualize his own sense of time wasting away in an endless grind. It is not that Sherlock has lost all perspective on what is meaningful to him: he agrees when Joan points out that he has his work, and Joan herself, and the very fact that he’s alive. However, he’s thought of those things so many times—obsessive as he is—that they’ve become “unmoored from all meaning,” his sobriety a thought bubble uncomfortably crowding in and out of his thoughts on a daily basis.

Here we have an example of a scene that is undoubtedly Craig Sweeny—the credited writer of the episode—using the thematic material of the storyline to create a pivotal juncture for this character and this relationship. However, whereas I would say on average such efforts tend to create anvil-like reinforcements of things we already know or anvil-like reveals of things we didn’t, this scene transcends its thematic origins by fittingly resisting the urge to function like a climax. Joan reacts as we would expect her to, reassuring Sherlock calmly and eventually simply asking if there is anything else she can do. I found Joan’s involvement in the scene particularly enriched by her absence from the Brownstone this season, her sense of concern driven in part by her sense of distance from Sherlock. And yet she still doesn’t treat this as a “major” crisis, acknowledging the weight of Sherlock’s words and the cumulative weight of her absence while emphasizing the quiet gravity of the situation rather than blowing it into something much larger.

The next morning, the show goes on: Joan gets a bugle wakeup call (delighting Sherlock, who has missed rousing her), they interview Dr. Kirk, and they eventually find the benefactor responsible for the murders. Although it may seem counterproductive at first, “The Eternity Injection” understands that Sherlock and Joan’s conversation is more powerful if it doesn’t stop the episode dead. It means more when Sherlock and Joan are together solving a case, standing over the body of a man who injected himself to try to experience eternity, with no clear idea of how it would affect his body. The parallel to Sherlock’s drug use is perhaps too obvious, but the show doesn’t make a huge point about it: indeed, the episode ends before a clear connection can be made, and before his paralysis can be framed as a climax instead of the anti-climax it really is.

Procedural episodes about time are often productive, as they call attention to cumulative storytelling in a way that episodes about other subjects can’t. We know that Sherlock has been battling sobriety for over two years because the show is in its third season, but hearing the character himself reflect on how much time has passed is meaningful. This season, Joan’s absence has further reinforced the sense of how time—whether separate or apart—shapes these characters, and how it will continue to do so moving forward. Although the case itself kind of peters out at the end, “The Eternity Injection” makes it work because it turns the idea of an anti-climax into a philosophical question, posed in a way that gives the show and its characters a pivotal idea to anchor its storytelling moving forward.

It’s plausible we won’t return to this theme in any more detail for weeks, if not months or years, but its presence—even subconsciously—enriches the show in ways that help separate it from its generic forebears.

Stray observations:

- I had enough to say that I don’t exactly have time to explore what function Odin the Car Alarm was playing in the episode—anyone want to offer a theory as to its thematic value, beyond the functional purpose of justifying Alfredo’s continued presence at the Brownstone and a fun running gag?

- You know, if you had told me that it was Headmaster Charleston who ordered the murder of innocent people instead of D’Angelo Barksdale, I totally would have believed you, because that guy seemed shady.

- This is weird considering that I’m certainly one of the show’s most focused viewers, but I don’t remember seeing a version of the credits that retains the “Mousetrap” sequence without the actors’ names. Curious how many differently-timed variations they have depending on how an episode clocks in, and how many I’ve missed over the years.

- Sherlock and Joan both backseat lockpicking Kitty was a delight.

- “I don’t mean to be rude, but your computers suck”—welcome back, Mason, the latest recurring Irregular.

- “It’s a wonderful morning to be preoccupied by the meaningless of existence”—this sounds depressing without hearing the tentative joy with which Sherlock said it.

- On Joan’s question of whether Sherlock intends to wake up Kitty: “Of course not, I am a courteous housemate.” (It was really so that Joan and Sherlock could focus on the aftermath of their conversation alone, but the joke is great too.)

- I refuse to believe that Everyone wouldn’t have supported Sherlock shifting his Twilight treatise to propose a threesome.

- Clyde Watch: Look, I’m not going to hold the absence of Clyde from this episode against them, as it was a strong outing, but surely there was room for a quick scene of Joan calling a neighbor to feed Clyde after spending the night at Sherlock’s. And then the neighbor could put Clyde on the phone, and Joan would ask Sherlock if he wanted to talk to Clyde, and Sherlock would decline and say that he would speak to him when he next took custody. And then the neighbor would hang up and say something to Clyde, at which point Clyde would bite him or her. Cue laugh track.