Elliott Gould on throwing his lunch at Robert Altman and Saturday Night Live’s Five-Timers Club

Welcome to Random Roles, wherein we talk to actors about the characters who defined their careers. The catch: They don’t know beforehand what roles we’ll ask them to talk about.

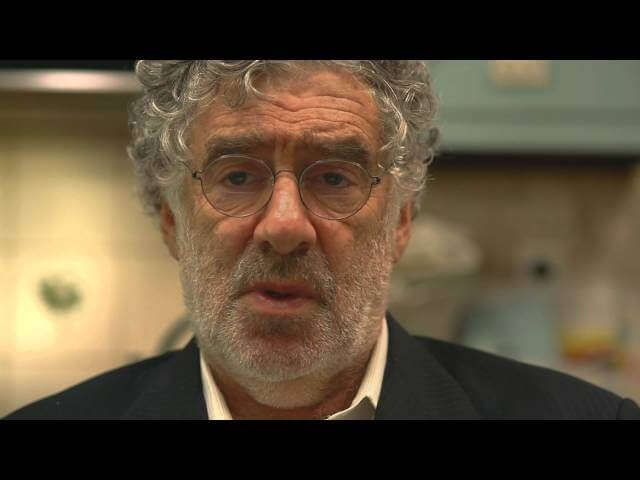

The actor: Elliott Gould entered show business early in life, learning about acting, dancing, and singing from “Charlie Lowe’s Broadway show business school for kids” before his age ever hit double digits, but it was his Academy Award-nominated turn in 1969’s Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice that kicked off his ascent toward becoming one of the most instantly recognizable actors of the 1970s. In addition to his big-screen performances in such films as M*A*S*H, Bugsy, and Steven Soderbergh’s Ocean’s franchise, Gould has also maintained a steady small-screen presence over the years, having joined Saturday Night Live’s Five-Timers Club and played Monica and Ross’ dad on Friends. Gould can currently be seen as part of the cast of Showtime’s Ray Donovan as well as in the film Fred Won’t Move Out, which is now on DVD.

The Caller (2008)—“Turlotte”

Fred Won’t Move Out (2012)—“Fred”

The A.V. Club: How did you come to appear in Fred Won’t Move Out? Did your agent pass along the script, or did the filmmakers reach out to you directly?

Elliott Gould: Well, Richard Ledes, who wrote and directed Fred Won’t Move Out, had cast me in a film in 2007 that I did with Frank Langella, The Caller. But with Fred… Do you recall the last name of Fred?

AVC: I don’t recall them mentioning it in the film, and it’s not on IMDB.

EG: All right. Well, I think we did the film in 2011, right around this time of year, in Westchester, actually, in a home that Richard Ledes had lived in with his parents. He sent me some notes that he had written and a synopsis of what he wanted to do, but not with a full script. He wanted to work on it while we were doing it, and I felt that it reflected an aspect of the human condition that interests me, in that I’m approaching this age. Since I completely believe in the family, and it’s what I work for, I thought it was something to do at the time.

AVC: Do you yourself have a personal connection to Alzheimer’s disease?

EG: Well, I do know people and there are people in my family who have had Alzheimer’s and dementia, and I appreciate the importance of communication and having contact with them. Communicating is an interesting thing with a condition like that. Sometimes it’s difficult to communicate. If the brain becomes atrophied or certain channels of the brain become atrophied, then contact is what becomes really important.

AVC: It’s a very realistic film, in that it’s an experience that numerous families have had to go through, but that also makes it a very difficult film to watch.

EG: Well, that’s life, you know? I thoroughly believe in evolution, and how we evolve and how our physical being is affected by time and use and by the environment… it’s more than just challenging, it can be terrifying. We all struggle, but I think it’s important to be there for one another.

The Confession (1964)—“The Mute”

EG: That was the beginning of my film career. The Confession was directed by William Dieterle, who had directed Charles Laughton as The Hunchback Of Notre Dame, Paul Muni in The Story Of Louis Pasteur, and Bette Davis in Juarez. I was cast to play Alejandro, this deaf-mute who’d been shocked into being deaf and dumb. [Hesitates.] I think he was deaf. I know he was dumb! But it was quite an experience. That was in the mid-’60s. Now when you find it on late-night television, it’s called Quick, Let’s Get Married. But the stars of the film were Ginger Rogers, Ray Milland, and Barbara Eden, who was in it with her husband at the time, Michael Ansara.

AVC: That’s not a bad cast or director to start your film career with.

EG: [Laughs.] Well, what I remember was that my first shot in a movie; my character was supposed to be drunk, and there were a lot of people there. I’d been a child performer in song and dance as well as a chorus boy, but I knew nothing about being in movies or the craft of movie acting. So I started breathing heavily, really hyperventilating, acting drunk and threatening Ray Milland… and somebody behind the director yelled, “Cut!” It was an elderly man who was the sound man, and he walked up to the director and pointed at me and said, “He’s breathing too loud! The shot’s been ruined!” And I thought, “If I can’t even breathe right, how am I ever going to learn to act?”

The Long Goodbye (1973)—“Philip Marlowe”

EG: As I was growing up, I would go to see film-noir films, the detective stories, and I thought Humphrey Bogart was the greatest. David Picker, who was running United Artists at the time, gave me Leigh Brackett’s script adapting Raymond Chandler’s The Long Goodbye and asked me to read it, so I read it. I was looking for a job at the time and… let’s say that finding a job wasn’t easy at that time, though I don’t know if it’s ever easy. There was another director who was going to be doing it, but he couldn’t see me in it. Then David Picker gave the material to Robert Altman, and Altman called me from Ireland, where he was finishing Images with Susannah York. Bob said to me, “What do you think?” I said, “I’ve always wanted to play that guy,” meaning Philip Marlowe. And Robert Altman said to me, “You are that guy.” So that was the beginning of that.

AVC: There’s been talk for some time of you teaming with Alan Rudolph to produce a sequel to The Long Goodbye.

EG: Yeah, I started to work on a sequel. I think I’ve basically read or narrated the books on tape of all of Raymond Chandler’s work, and I discovered “The Curtain,” which was written before there was a Philip Marlowe. The Chandler estate worked with me when I was more involved in it, although I’ll never give up on it. For as long as I can, I’ll try to work on getting a sequel to The Long Goodbye. I had a treatment developed and gave it to Bob Altman, and we started to talk about it, but then Bob passed away. But Alan Rudolph was the second assistant on The Long Goodbye, and Alan wrote quite an excellent first draft. But I haven’t been able to finance it.

The estate had given me permission at the time—this was just a few years ago—to change the name of the character, because the private eye was called Ted Carmady. It was written by Chandler before he wrote The Big Sleep, but you could see where The Big Sleep came from. In the story, there’s a 10-year-old son of the character that Bacall played in The Big Sleep, and the son is the killer. That’s what attracted me to it. It would take place now, and the character of Philip Marlowe is now a much older man, like me, but he still has the same values. It’s something that could conceivably work if it’s free to express itself the way I feel it and see it, but whether it’ll ever happen remains to be seen. But I’m just eternally grateful for Robert Altman and David Picker giving me the opportunity to participate in The Long Goodbye and play Philip Marlowe.

E/R (1984-1985) —“Dr. Howard Sheinfeld”

EG: I remember getting a call from Jean Guest, who was a family friend and who is the mother of Christopher Guest. Jean was casting for CBS, and they invited me to participate in the pilot that Embassy Television was producing for CBS: E/R. This is prior to the hourlong show that became such a big hit. This was a half-hour situation comedy based on a play called Emergency Room that the Organic Theater in Chicago had developed. So they cast me, and in the course of the 22 segments that we produced and did for the network, we were able to introduce George Clooney and also Jason Alexander. And Marcia Strassman, who always reminded me a bit of Lucille Ball, she was originally the supervisor who Howard worked for and an emergency-room expert, but they replaced Marcia after the pilot with Mary McDonnell. It was an amazing experience for me. It was my first experience doing a series.

AVC: Pamela Segall was also in the cast, who went on to work with Louis C.K.

EG: Isn’t that great? And Dennis Franz was in one of the first episodes, too. He brought somebody into the emergency room. We had a lot of really good people come on.

Bugsy (1991)—“Harry Greenberg”

EG: The thing that I remember was when we were doing the scene in which Harry Greenberg came to Benjamin Siegel’s house in Hollywood after it was evident that he had talked and was living on borrowed time. In the scene, Harry Greenberg says to Ben Siegel—well, the screenwriter wrote “incognito.” I thought, “‘Incognito’ is such a sophisticated kind of concept, and a guy like Harry Greenberg wouldn’t necessarily be so adept with language,” so I said, “igcogneato.” I actually did it about 14 times: “I thought I could be igcogneato.” I just loved that. So that was my contribution. And without questioning it, it was in the film. It isn’t in the published screenplay, though. I wish it was. I don’t need credit—James Toback wrote the screenplay—but I just wish it was in there. But it was an interesting experience, and the critics and the people were extremely supportive about the character I played and how I played it.

AVC: You’d been friends with Warren Beatty prior to the film, but how was he to work with?

EG: Well, he didn’t direct Bugsy. That was Barry Levinson. But with Warren… I felt like the essence of where Benjamin Siegel came from, underneath the gloss of the handsome killer Bugsy Siegel, he was like Harry Greenberg. They came from the same place, they knew one another as children. So in the scene, we were on a train, and Harry Greenberg asks Benjamin Siegel for some money, and… in movies, when you’re on a bell, it means that sound is going, and you’re just a heartbeat away from action and acting. And Warren suddenly said to me, “Do you like to rehearse?” And I thought, “Gee, I’ve never heard anyone want to rehearse once we’re on a bell.” But then I thought, “Well, Warren is like that. He likes to do it over and over and over and over again until he feels it’s perfect… or at least he’s perfect.” [Laughs.] Barry Levinson directed the picture, but Warren was playing the leading role, and Warren Beatty is Warren Beatty, so I said, “Okay, we’ll do it ’til you’re happy.” I was a tap dancer as a child, so I understand precision and repetition.

Ocean’s Eleven (2001) / Ocean’s Twelve (2004) / Ocean’s Thirteen (2007)—“Reuben Tishkoff”

EG: I was working in Ireland, and I was picking up messages from L.A., and Jerry Weintraub had called me and asked to talk to me. I called him back, and he asked if I would meet with Steven Soderbergh once I was back in the country. So they made an appointment for me to meet Soderbergh at the Daily Grill on La Cienega, and after we met, he cast me.

[pagebreak]

AVC: How was working with that cast of relative youngsters?

EG: It was great. George Clooney is a fabulous guy. He’s very generous, lots of fun, very intelligent. And he set the tone. Brad Pitt was a terrific guy, and I became friendly with Matt Damon and… well, everyone, really. But I really picked up on Casey Affleck during the film. I called him “Maestro.” He bit his nails lower than I ever bit mine… and I used to bite mine to the quick! [Laughs.] Originally, Alan Arkin was going to be playing the part that Carl Reiner played, but then Alan had some sort of medical situation and couldn’t do it, so we got Carl. Bernie Mac was a great guy, and we miss him. It was great working with Steven Soderbergh and Jeffrey Kurland, who did the wardrobe. The choice of wardrobe, even the glasses, that was Jeffrey Kurland.

I mentioned that I’m friendly with Casey, but I’d never really talked with Ben, so I decided to go to a gathering recently that George Clooney was having, a party for the cast of Argo. When I told Ben that I was there because I wanted to say hello and let him know how impressed I am with his craft, I think he was pleased, but then he asked me a question, which I thought was really great. He said, “Have you ever done anything in all of this that you were sorry you did?” And I took a moment, and I said, “No, because there’s so many people dependent on our work for their living or their livelihood. You do something whether it works or whether it doesn’t. Once you’re committed and you do it, it becomes a part of your life. I wouldn’t be sorry about it. I’d learn from it.” So I felt that I was able to impart at least a little bit of wisdom to him.

Once Upon A Mattress (1964)—“Jester”

EG: With Carol Burnett! Oh, gee, thanks… and I’m not being sarcastic! [Laughs.] Matt Mattox actually created the role. Once Upon A Mattress was off-Broadway, George Abbott directed it with Carol Burnett, and Matt Mattox played the court jester. He was one of my teachers—a great guy and a real athletic dancer. He’s in Seven Brides For Seven Brothers, and he was in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes. Then Joe Layton directed this live two-hour prime-time production of Once Upon A Mattress with Carol Burnett reprising her role, and he had me come in and audition for [producer] Joe Hamilton to play the court jester, and I got the part. In our chorus, by the way, was Michael Bennett, who went on to create A Chorus Line. At the very end of our show, for the final credits, they had people from the chorus holding up mattresses, and one of those people is Michael Bennett.

California Split (1974)—“Charlie Waters”

EG: Joseph Walsh wrote the script for California Split, and then eventually Robert Altman directed it, although at one point Steven Spielberg was going to do it. But Joey Walsh and I lived [it] together, and in the movie, George Segal plays me. [Laughs.] It’s semi-autobiographical. I played Joey, which was Charlie Waters, because one of Joey’s brothers was named Charlie, but we thought Steve McQueen was going to be doing it. When I was working abroad in Munich—and I almost dare you to find that picture [Laughs.]—it was called Who? But I believe Steve McQueen wanted something in the script that wasn’t there, so Bob Altman called me and asked me if I would play Charlie Waters.

I said, “I’ll do anything you want me to do,” because that was going to be the third picture I’d done with Bob Altman. When he offered me McCabe And Mrs. Miller and I couldn’t do it because I chose to do I Love My Wife at the time, he said, “You’re making the mistake of your life.” And I said, “Well, it’s not my life yet, and you can’t take away that I was your first choice. Someday I’ll look back and say, ‘What a masterpiece… and you were gonna cast me in it!’ Meanwhile, Warren Beatty and Julie Christie will be beautiful!” So for Charlie Waters, I said, “What about Joey? He wrote it. It’s his picture. What does he say?” He said, “Joey’s playing poker.” I said, “Well, if it’s okay with Joey, and you want me, then I’m there.” So that’s how I came to play Charlie Waters.

American History X(1998)—“Murray”

EG: Oh, my gosh, that was with Tony Kaye. When I went in, [producers] Larry Turman and John Morrissey, they had me come in to meet Tony Kaye and to read. I was interested in doing it, being a Jew, so I went in and I actually read. And Tony Kaye, who was a commercial director and a very interesting guy, had me read it over and over until the producers said, “Enough already!” So they cast me. Paul Mazursky told me he wanted to play the part, but I just wanted to reflect on the insanity and the ignorance of that kind of passion being used in such a biased way, in such a destructive way. I just wanted to face it.

Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice (1969)—“Ted”

EG: When I first read Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice, it frightened me, and I didn’t think I would do it. I thought it might be exploitative, and I was extremely uptight—very much like that character, but uptight about my lack of understanding and my lack of experience and my ignorance as to human relations. But then Mike Frankovich, who produced the picture at Columbia, sort of wanted me… for whatever reason. So I listened to Larry Tucker and Paul Mazursky’s tape of the improvisation of the bedroom scene between Ted and Alice, and I could see that it was funny. It was very funny. So I said I would do it.

Then I was asked if I would do some casting to find the Alice, which was interesting. Karen Black was up for it, and I thought she was fabulous. But I had met Dyan Cannon and, of course, her husband back then, the great Cary Grant, and he was very nice to me and Barbra [Streisand], my wife at the time. I was very insecure about doing the test, because I thought they would see that I wasn’t very good. [Laughs.] I mean, this was only going to be my third film!

With Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice, each of the characters had a fantasy, and Alice’s fantasy was that every man in her mind wanted to dance with her, so Mazursky staged a scene with 400 male extras and me and Dyan Cannon. So we were rehearsing and setting it up, and the camera was set up and it was all lit and whatever. But they had to break for union regulations, because we had all those people there, so they turned the lights off, left the set the way it was, left the camera there. As usual, I had no place to go, and I stayed on the set… and there was the camera. And I thought to myself, “Oh, the camera doesn’t give me problems. I give me problems. The camera will never lie to me. It’ll never manipulate me. It’ll only report what I’m doing. I can see myself honestly.” And that was my first objective relationship in existence: with the camera, which has been my friend ever since. That was the only Academy Award nomination I ever had, but I was and am grateful for it.

The Muppet Movie (1979)—“Beauty Contest Compere”

The Muppets Take Manhattan (1984) —“Cop In Pete’s”

EG: Oh, that’s good. It’s so wonderful just to hear you say those. [Laughs.] Well, it happened because I had done a film for Lord Lew Grade. There were three brothers—Lew and Leslie Grade and Bernard Delfont—who were Cockney song-and-dance guys who made it on their own. The first picture I did for Lew Grade was Capricorn One, which was somewhat of a success, and then I was set to do another picture, Escape To Athena, so I therefore had the balls to call him up and say, “I must be in The Muppet Movie! My children love the Muppets! And I know the Muppets; I’ve worked with them on Saturday Night Live! I just adore them!”

Jim Henson was great to me and my kids. I loved him. So they put me in. I wasn’t in the script, but they cast me for half a day or so, where I was the mayor of the town where Kermit comes in. And there’s a beauty contest, and my judges for the beauty contest were Edgar Bergen and Charlie McCarthy. Edgar Bergen was Candice’s father, Candice worked with me on Getting Straight! So then I got to introduce Miss Piggy to the big screen. I was so grateful for that. Then later on, when they did the next Muppet movie, The Muppets Take Manhattan, I had just been fired from a show that I was trying to do on Broadway called The Guys In The Truck. So there I was in New York when they called and said, “Would Elliott come and just play a little bit part?” And of course I did. I’ve been told that I’m one of few actors, if not the only, who’s done more than one Muppet movie.

WordGirl (2008) —“Masked Meat Marauder”

EG: [Long pause.] Now hold on a second. Was this an animated thing? I kind of remember it. I mostly remember that the guy who played Luke Skywalker [Mark Hamill] was there. [Laughs.] I have a lot of experience, but I didn’t have too much experience doing voice acting, so it was a challenge to be directed in doing a voice that I wouldn’t ordinarily do. But I did it. I don’t deny anything.

Kicking And Screaming (1995) —“Grover’s Dad”

EG: Oh, of course, this was Noah Baumbach’s directorial debut. Noah came to visit me, and he wanted me to do it. God, I loved that actor who played Grover. He’s fabulous. Josh Hamilton, isn’t that his name? He’s a wonderful actor. I think he’s just great. He plays a peculiar part in Frances Ha, which I saw him in. The guy has great integrity, as does Noah Baumbach. And his mother [Georgia Brown], for that matter. So I was pleased to do Kicking And Screaming. He also cast my son Sam in a small part in that, too.

[pagebreak]

A Bridge Too Far(1977)—“Colonel Stout”

EG: Joe Levine and Richard Attenborough were putting together this mammoth production, based on the novel by Cornelius Ryan, the guy who wrote The Longest Day. I flew to Joe Levine’s home where he was having a party, and he said, “You’re the only actor I have here!” [Laughs.] I loved Joe and [his wife] Rosalie.

They were casting me as a character named Bobby Thompson, who was supposed to parachute in and maintain control of the rooftops in whatever city it was. But I remember saying to Richard Attenborough, who’s a great guy, “You know, I will play the guy, but there was another Bobby Thompson who broke my heart. He was called the Flying Scotsman, he played for the New York Giants, and he hit a home run in the playoffs in 1951. It was a nightmare for me. It was the worst thing that ever happened to me, because I was a Brooklyn Dodgers fan.” [Laughs.] But then they called me and asked me to play a part that they’d been after Robert De Niro to play for a very long time, but they weren’t able to get him. It’s actually the only character, as far as I know, that’s not in the book. Joe Levine wanted Bill Goldman, who wrote the screenplay, to add a colloquial American who came from another place, hence Bobby Stout.

[The baseball player for the 1951 New York Giants was Bobby Thomson. —ed.]

So I was very happy to play it and to be a part of the film, and after I finished my assignment in it, I went back to London—because we shot the picture in Holland—and bought a watch, which I ended up giving to my son Jason, and I had it inscribed with his name, the date of his birth, and the words, “There is no bridge too far. Love, Dad.”

Little Murders (1971) —“Alfred Chamberlain”

EG: I had done the original production of Little Murders onstage, which was produced by the wonderful Alex Cohen. I still speak with Jules Feiffer, who wrote it, but I had been sent to meet Jules with the thought of directing it. I guess people thought I was going to be a director, and I’ve always been interested, but Ingmar Bergman said to me directly—I’m not paraphrasing—“When you direct, and you will direct, you mustn’t act. You’ll understand what I’m talking about.” So Marty Bregman, who was a friend at the time and also was our business manager, flew me to Martha’s Vineyard to meet with Jules Feiffer, and there was no way Jules was going to allow or even consider me to direct it. [Laughs.] But then they asked me if I would read for Alfred Chamberlain, which I did, and I was able to play the part. It was a very difficult part onstage. The material was very demanding.

I also produced the film version of Little Murders, and that was the most hands-on I’d ever been. Our cinematographer was Gordon Willis, who’d only done one picture at the point we worked with him, and our camera operator was Michael Chapman, who went on to direct Tom Cruise in All The Right Moves. Donald Sutherland is at his best in it. He plays the priest. Marcia Rodd is terrific, but I wanted Jane Fonda. The problem was that I didn’t know how to talk to Jane Fonda. We went out to dinner, Jane and me, and I just turned into Bert Lahr. [Laughs.] She was just so sexy, I didn’t know how to talk to her! I’d talked to her father, Henry, who’d told me that Jane had the same work ethic as Barbra, so all I would’ve had to say was, “I’m doing a picture, I’d like you to star in my picture, please read the script, and I hope you will consider doing it.” But all I could do was go… [Does a Cowardly Lion stammer.] But it all worked out, because Marcia Rodd did great.

The play didn’t succeed on Broadway, but then Alan Arkin directed it off-Broadway—and, actually, Chris Guest was in it!—so we hired Alan to direct the picture. Everybody’s great in the film—Jon Korkes, Vinnie Gardenia, and Elizabeth Wilson, who played the mother. She was a very good friend of Katharine Hepburn. And Lou Jacobi played the judge, and in addition to directing it, Arkin also played the psychotic detective. The whole thing was very gratifying. It took a long time to get it on DVD, but there’s a running commentary, which is simply Jules Feiffer and me, with me thanking him for Alfred Chamberlain. [Laughs.]

M*A*S*H (1970)—“Trapper John McIntyre”

EG: To start this story, I have to tell you about the first time I was fired. I was fired twice from Broadway shows, and I mentioned one to you earlier, but both times the shows didn’t work. This one was called A Way Of Life, a play by Murray Schisgal that I had auditioned for prior to participating in Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice, but I went into the rehearsals, and first they fired the director, then they fired me. I don’t even know if it ever opened. [It did not. —ed.] But I came back out to California and was asked to meet Robert Altman.

So I went to 20th Century Fox and met him in his office, just the two of us, and he gave me the script by Ring Lardner Jr. I read the script, I came back, and he said, “Would you consider playing Duke?” This was the American Southerner, which went on to be Tom Skerritt’s part. I said, “I’ve never questioned an offer, but I’ll drive myself crazy. I’ll be so intense being an American Southerner. I could do it, I have an ear for accents, but… if you haven’t cast this character of Trapper John, I’ve got the juice, I’ve got the energy, I’ve got the spirit that you want for that. And the heart.” And he cast me. It’s like he let me cast myself. And the rest is history!

Then he asked me to have lunch with Donald Sutherland alone—Donald was cast before me—at the commissary at Fox. When we sat down to lunch, the first moment, I felt we didn’t like one another, but Donald and I became very, very close. How it worked was that Donald and I would be together, we were both inseparable during the course of that production, and then Bob was directing us. But there was this one scene where both Donald and me, we were a little taken aback by the way Bob was working. Donald and I were coming from different places, but we were two people who both took ourselves very seriously. You know, a couple of asshole actors. [Laughs.] And we weren’t getting how innovational Bob was being. Bob thought we wanted to get him fired. We didn’t, but we didn’t understand what he was doing, either, so we complained about him. On a Saturday, we met with Dick Shepherd, who was our agent, and we complained, and then Bob painted me after the picture as being his enemy. Well, you know how I feel about Bob Altman now. I was so blessed to be able to get past myself ,to do the work that I was able to do with him, and I’m honored that he liked me.

There’s one scene where we’re all playing poker, the guys from the other camp who were going to play football are there, and Bob said to me, “In the scene, I want you to turn around and look at the guy wearing sunglasses with mirrors on them, and when you realize that he’s standing behind you, I want you to say to him, ‘There’s two ways of getting killed in this war: You go out on the front and you fight, or you stand behind me wearing those glasses when I’m playing poker.’” But then Bob said to me, “I can’t keep my eyes off of you. It’s distracting.” I said, “So don’t look at me, then. I’m always in character, Bob. Look at what I’m doing in concert with what you’re shooting, and then you tell me and I’ll make an adjustment.” And the next day he came back to me after he saw the dailies, and he said, “You’re right.”

Sometimes Bob could get flustered, because he sometimes would be given a hard time by management. Historically, the studio would give Bob a hard time because he was so inventive and so original. So there was a crane shot that had to move over a body of water, but now we’re looking at the time, and we’re approaching lunch… and if you get to lunch, they call it the golden hour, where the people get paid a lot of extra money. So Bob was really pressing, and he was a little flustered, but we were able to get it. It’s in the picture. And then we went to lunch. Corey Fischer was there, who was one of the members of The Committee, an improvisational political comedy group from San Francisco, and Bob said to me, “You’re ruining it for me! Why can’t you be like someone else?” And he pointed to Corey Fischer, which… I mean, I loved Corey Fischer, but the idea that I should be like somebody else? That I should act like somebody else? Well, I revolted. I started shaking, I threw my lunch, and I said, “You motherfucker! Fuck you, man! I’m not gonna stick my neck out for you again! Just tell me what you want, and that’s what you’ll get!” And Bob said to me, “I think I made a mistake.” And I said, “I think so!” And Bob said, “I apologize.” And I said, “I accept.”

By the way, that scene… later on, Sylvester Stallone said to me that he was there that day. He was an extra. And he said to me, “I don’t admit that I was an extra in many pictures, but I admit that I was an extra in M*A*S*H.” I thought that was sort of touching. But I told Bob Altman, and he said, “No! I do not accept that! I do not accept that Sylvester Stallone was an extra in my movie!” [Laughs.] God, Robert Altman… You’ll bring me to tears. I mean, he was like my father. I just loved him, and there was so much other work, more work that we talked about and would’ve loved to have done together.

Friends (1994-2003) —“Jack Geller”

EG: They’d done a pilot, they’d been picked up by NBC, and I knew they were going to be on around Mad About You and Seinfeld, but they were not yet in production. They sent me a script, and… there wasn’t much in it, but they wanted me to play the father of David Schwimmer and Courteney Cox. I didn’t know if I’d do it. There wasn’t much money in it for me, so I didn’t think I would do it, and my agents didn’t want me to do it at the time, either. But then I saw on the script that it was to be directed by Jim Burrows. I’d worked for Jim’s father, Abe, who directed Say, Darling, where I was third assistant stage manager and I was a chorus boy, just a little part. But that was one reason why I wanted to work with Jim Burrows. That, and to see how he did it, because he was so successful. So I wound up doing it, and we got along great. And all the Friends were very nice to me, too.

Saturday Night Live (1976-1990)—Host

EG: Oh, that was great. I didn’t stay up so late to watch it, but Jenny [Bogart] and Gary Weis, who was one of the contributors, they said I should do it, so I went in and did it, and it was a great experience. Lorne [Michaels] and I are still friendly. In fact, we just did a pilot together [The John Mulaney Show].

The first show, I wore my Indian jacket, and I had my moustache, because I was doing Harry And Walter at the time, Paul Shaffer played the piano for me, and I sang “Let Yourself Go,” and then I went into “Crazy Rhythm.” Like with Miss Piggy in The Muppet Movie, I got to introduce Paul Shaffer on Saturday Night Live, and Paul said he’ll always remember that. On the second show, I did the verse of “Anything Goes,” and I said, “And tonight, everything goes!” The third show, I was all set to do another old-fashioned medley: first the verse to “All The Things You Are,” then “Don’t Fence Me In,” and finish with “You’ve Gotta Have Heart.” But then they said to me, “We’ve written an original song that we really want you to consider. It’s called ‘The Castration Walk.’” I said, “Get out of here! I’ve got these songs!” They said, “Would you please consider it?” And it’s hysterical. So I did “The Castration Walk” with Bill Murray and John Belushi. It’s so funny, the three of us doing that.

AVC: You came back to the show to appear in the first Five-Timers Club sketch, but then you were absent for the one they did recently.

EG: I was. I made an error with that. They wanted me to do the Five-Timers Club with Justin Timberlake, but I’m working out here doing Ray Donovan, and I worked until 1 in the morning that Friday night and was preparing for a big scene, my first with Jon Voight, that I had to have memorized. So I opted not to go in. But I wish I had. It was so great. I’m sorry I didn’t. I could’ve gone, and I should’ve gone, but I said to Lorne, “I hope you have me again, because I’ll come next time.”

Ray Donovan (2013)—“Ezra Goldman”

EG: I’ve known Jon Voight forever. As a matter of fact, I knew his first wife, Lauri Peters, before they met—she actually worked on Say, Darling. David Steinberg introduced me to Jon, who’s just fabulous. This is the first time we’ve acted together. Before we did, I said, “This is gonna be like Laurel And Hardy on acid!” [Laughs.] It’s a good part. And Liev Schreiber is very, very good. Ann Biderman, who wrote Public Enemies for Michael Mann, is the creator of it.

Ezra Goldman is a very high-powered lawyer and agent in this town, who employs Ray Donovan and also advises Ray Donovan. Some of what I drew from was David Begelman, who’d been my agent, and also a little tiny bit of Lew Wasserman, who always seemed to respond to me, although I did only one picture at Universal. He’s an interesting guy, and at first it seems that Ezra Goldman has the beginnings of dementia, but it turns out, as the show progresses, that it’s not dementia. He has a growth on his brain, a tumor, and it gets operated on. We’ve done 12 segments—I was contracted to do five, and I ended up doing eight. We’ll see if there’s a future for it… and possibly even for Ezra Goldman!

The Touch (1971)—“David Kovac”

EG: Oh, wow. You know, I thought you might’ve closed with Harry Bailey [from Getting Straight], but, no, I’m right there with you on that one. Someone at UCLA once asked me the difference between Ingmar Bergman and Robert Altman, and I said, “Well, Robert Altman knows who Dave DeBusschere was, and Ingmar never heard of him.” [Laughs.]

Okay, so I was making a living for the very first time in my existence. Here I was, and I was really so hot. Can you imagine? It was so unexpected that someone like me would break through. [Laughs.] Then I hear from David Begelman that I was No. 1 on a list to do Ingmar Bergman’s first English-speaking picture! They sent me the script, and… it was not a script like the scripts we usually see. It was like a novella. And there’s a scene where Bibi Andersson’s character, Karin Vergerus, and my character have violent intercourse. Well, I immediately got a migraine headache, because I thought, “How can I expose my ignorance and my lack of relationship on that level? But I can’t say no to Ingmar Bergman! Let’s see if he’ll call me in the West Village.”

So Ingmar called me, and… I, uh, don’t really imitate anyone, but I do imitate Ingmar Bergman and John Huston, because they both had such great voices. [Launches into a Bergman impression.] “No, no, no!” And the hair on my neck stood up. It was hilarious. So I thought, “Oh, I can trust me with him and him with me,” not knowing how far we were going to go. So I acquiesced to come. I thought, “Well, let me learn. I’ve got a lot to learn, I’ll work with some of the best actors in the world—Max von Sydow and Bibi Andersson—and I’ll see if I can keep up with them.” Also, it appeared that I had a really fertile future in production [after Little Murders], but I didn’t know about business, and I thought I could learn about that from Ingmar, too, which I did.

In his autobiography, Ingmar ultimately dismissed The Touch, along with the rest of his English-speaking pictures, but I’ve endured, the film is a fucking masterpiece, and it’s like the song goes: You can’t take that away from me.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from The A.V. Club.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from The A.V. Club.