Embrace Of The Serpent is a head trip that explains itself too much

If Colombian writer-director Ciro Guerra’s Embrace Of The Serpent is to believed, then there was a time when the Amazon was crawling with failed Christ figures, and one couldn’t traipse 10 feet into the jungle without tripping over a metaphor for the destruction of indigenous culture by the rubber industry or an Alejandro Jodorowsky-esque death cult. Rubber trees dripped milky latex through scores in the bark, suggesting open wounds, a land being bled dry, or possibly stigmata; at the roots of the largest rubber tree grew the fictional yakurna orchid, said to possess curative powers understood only by the Cohiuano people, also fictional. As Embrace Of The Serpent pictures it, the Amazonian jungle in the first half of the 20th century was a place of wounds, scars, and ailments, both physical and psychogenic. The only way to travel was by the water, in which symbols swam like fish.

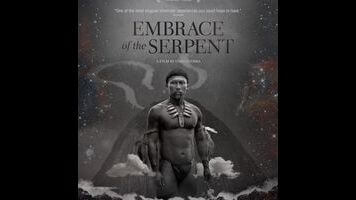

Is it possible for a movie to be too perfect a dialectic, or too smart for its own good? Part black and white road movie, part corrective to colonialist adventure yarns, Embrace Of The Serpent tells two stories that, as the movie insistently points out, are really the same story, involving the opaque figure of Karamakate, the last of the Cohiuano, and the white scientists who come to him in search of yakurna. Inspired by the writings of the German ethnologist Theodor Koch-Grunberg and the American botanist and psychedelic researcher Richard Evans Schultes, who studied the indigenous peoples of the Amazon decades apart, Serpent has fictionalized versions of both men (“Theo,” the Christian connotations of whose name Guerra can’t resist, and “Evan”) seeking out Karamakate, played as a young man by the athletic Nilbio Torres, and as an older one by the barrel-chested Antonio Bolivar.

Theo (Borgman’s Jan Bijvoet) comes to him sometime in 1900s, shivering with malaria as though he were suffering for the white man’s sins; Evan (Brionne Davis) arrives decades later, with a copy of Theo’s diaries in his knapsack. (The actual timeframe of the second expedition is intentionally kept ambiguous until the very end.) Off they go, traveling up the river, passing the same points, and encountering imagery both animist and Christian. If the first expedition, rounded out by former plantation slave Manduca (Yauenkü Migue), brings to mind the biblical wise men bearing gifts in search of a vision of rebirth, then the later expedition is literally mistaken for them, by the crazed occupants of a former Catholic mission, who exist in a bizarre world of ritual and punishment. (“They have become the worst of both worlds,” says Karamakate, in case the audience doesn’t get it.)

One key difference between Serpent and the movies it’s indebted to—namely Dead Man and the madman vs. nature films of Werner Herzog—is its resistance to the unexplained. There’s a preponderance of ironies (“Don’t believe their crazy tales about eating the body of their gods,” says Karamakate to a gaggle of Christianized orphans) and rhymes, often explained out loud. Children escape the lash of the rubber plantation only to be whipped by Capuchin monks; if the viewer doesn’t catch on that the camerawork is meant to be a reference to early ethnographic photography, then the dialogue is there to point it out. Whenever the movie teeters on the edge of poetic madness—like when Manduca voices his belief that Theo represents the redemption of the white colonials—Guerra’s commitment to thesis is there to pull it back into the literalism.

Shrewd at tweaking the clichés of colonial fantasy, Embrace Of The Serpent is ultimately an academic exercise, full of stand-ins and signifiers—a kind of Velvet Goldmine for the destructive impact of the South American rubber trade, minus the sense of decadent fun. There is an undeniable appeal to a movie that’s made to be picked apart and analyzed as much as this one is, where the props seem to be cross-referencing each other (Theo’s old-fashioned view camera and Evan’s twin-lens Rolleiflex), every incident and character has a mirror image, and even the protagonist is played by two people. One just wishes it weren’t doing all the work for the viewer.