Can there be such a thing as too many Scientology exposés? Given the volume (and nature) of the allegations that have been made against the church over the years—reports of abuse, stories of bizarre behavior and rituals, shocking testimonials from former members—any attempt to tell us more about the inner workings of that organization feels like a public service. Still, after numerous magazine articles, a few books, a television series, a comprehensive documentary, a pretty brilliant episode of South Park, and a boldly fictionalized version of the L. Ron Hubbard story, one would hope that a new film on the topic might possess at least a few fresh nuggets of wisdom or information. My Scientology Movie has very little of either to offer. Instead, this stunt-driven nonfiction project rearranges the well-reported dirt on the church, placing it into the context of something considerably less useful: a documentary about how hard it is to make a documentary about Scientology.

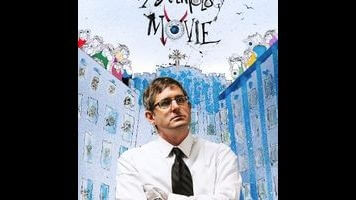

The “my” of the title refers to journalist and popular BBC television host Louis Theroux, who discovers very early on that any access to the church or its leadership will be strictly prohibited. Alex Gibney got around this problem just fine in Going Clear, relying on extensive interviews with the excommunicated and laying out an exhaustive history of the movement. My Scientology Movie scores a couple high-profile talking heads of its own (including arguably the most vocal of the renouncers, Marty Rathbun, who becomes a key creative collaborator), but it largely forgoes background info on Scientology, beyond some cursory exposition and clips from the group’s absurdly bombastic recruitment videos. Instead, the main draw is the pushback from the church—or more specifically, the dogged, deadpan response to it from Theroux, who looks like a less animated John Oliver and behaves like a politer Michael Moore. Perhaps recognizing that most of the movie’s insider insight is old hat, director John Dower leans heavily on Theroux’s personality, playing every pregnant pause in conversation for cringe comedy or tension.

To illustrate the church’s alleged behind-closed-doors practices, a kind of improvisational theater troupe play-acts the rituals, from the one-on-one insult appointments to the reportedly regular tantrums by Scientology leader David Miscavige. These passages are staged not like the hyper-slick dramatic reenactments of an Errol Morris movie but transparently: My Scientology Movie takes us through the casting calls, as Theroux auditions young actors to portray Miscavige and Tom Cruise, then focuses heavily on the process of “directing” each scene. None of these black-box acting exercises are remotely as upsetting as just hearing lapsed Scientologists describe their traumatic memories, but they’re arguably not for our benefit anyway; Rathbun is always watching from the sidelines, providing notes and guidance, and an early comment from Theroux about “putting him back in the mindset” suggests a kind of diet Act Of Killing, with the goal of making the man confront his own role in the abuse he claims to have witnessed, and later decried. But the contentiousness between the filmmaker and his subject never moves much past some light testiness, nor does any major breakthrough arrive. (The ending, to put it mildly, is anticlimactic.)

“For years, my dream was that I might see another, more positive side of the church as a journalist,” Theroux insists at the onset, laying out his supposedly pure intentions. But you can practically see a glimmer of joy appear in his eyes when that first white van appears behind him in traffic and representatives of the church start investigating him. Over and over again, My Scientology Movie presents the same scene: Theroux showing up to some Scientology outpost, then acting surprised when he’s told to leave, or getting into a passive-aggressive “No, why are you filming me” confrontation with Miscavige’s faithful followers. There’s no real ethical breach in serving people notorious for harassment a little of their own medicine. But that doesn’t make seeing Theroux bounce unproductively against the church’s interference tactics any more illuminating. We’ve heard too much about Scientology already to be shocked by any of this.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from The A.V. Club.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from The A.V. Club.