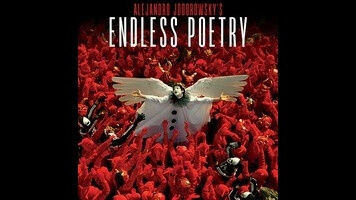

More wigs, more mandarin collars, more anachronisms, more phalluses, more Jungian megalomania: The octogenarian, Chilean-born director, comics writer, and guru Alejandro Jodorowsky (The Holy Mountain, El Topo) continues to plumb his early life in Endless Poetry, the sequel to his autobiographical comeback of sorts, The Dance Of Reality. The time is now the early 1940s. The teenage, still virginal Alejandro (Jeremias Herskovits and Adan Jodorowsky, the latter closer to 40) is ready to leave behind his macho father, Jaime (Brontis Jodorowsky), and his long-suffering mother, Sara (Pamela Flores, who sings all of her lines in operatic soprano), to make it as an avant-garde poet in the bohemian circles of Santiago. He is properly outfitted with a futurist collarless jacket—the start of a lifelong love affair, perhaps—and one of those Jean Cocteau or Sergei Eisenstein Bride Of Frankenstein ’dos that attached themselves to the heads of artistic white men with curly or wavy hair in the 1930s and refused to let go until the ’50s. Not to go off on tonsorial matters, but these haircuts are more or less the only realistic period details that interest Jodorowsky; it’s probably because they successfully evoke a time when the heads of Chile’s creative young men looked like they were exploding into space. Otherwise, he depicts his younger self hanging around all-night cafés that look like Kubrickian limbos; portrays his fellow bohemians as luchadors and ballet dancers; and pictures the seminal poet Stella Díaz Varín (Flores again, totally unrecognizable) as a buxom, frequently naked red-haired new-wave punk straight out of Derek Jarman’s Jubilee.

There, too, is the disembodied head of Jaime, which balloons and bounces around the room like something out of a silent Georges Méliès trick film, shouting “Faggot!” at Alejandro as he tries to scribble his first poems; the violin that his parents present as a more acceptable way of channeling his artistic pursuits, and which comes encased in a little coffin; and his mother’s family, whose overbearing Ukrainian Jewish roots take the form of a rabbi and an old man in an embroidered vyshyvanka who hang in the background like permanent house guests. As in The Dance Of Reality, the narrative is rambling, surreal, and highly personal, with the elderly Jodorowsky popping into scenes (albeit less frequently than in the earlier film) to address his past selves. But with a few exceptions, there is little of the bitingly funny anti-authoritarian streak that the filmmaker brought to Dance’s exorcism of the psychological demons of his 1930s childhood. Instead, his new film is more of a bildungsroman, something along the lines of The Sorrows Of Young Alejandro: heartbreak, unrequited love, initiation, artistic self-discovery.

Of course, it’s self-indulgent, pushed even further into patience-testing territory by cinematographer Christopher Doyle, who delivers some of the ugliest camerawork of his career only to bound to the rescue in unexpected moments with one of those tender mixes of color temperature (a gold bulb by a blue window, a spot of red washing a character’s hair from overhead) that have made his 1990s work so influential but difficult to imitate. But any viewer looking for restraint in a Jodorowsky movie has been badly misinformed. Parable-spouting, cult-leader-like magnetism is the guy’s whole brand; Jodorowsky loves to talk about Jodorowsky with the help of other Jodorowskys (Brontis and Adan Jodorowsky, who play father and son, are his children), but makes few excuses in his self-extrapolations. In one sequence of scenes in Endless Poetry, for instance, he depicts the young Alejandro’s relationship with a gay friend who harbored a crush on him, picking apart his own insensitivity and insecurity (he lets said friend kiss him, but only to prove to himself that he isn’t “a faggot”) while trying to imagine the young man’s turmoil in a conversation with a symbolic muse. Coincidentally, these are some of the most beautifully shot scenes in the film, suggesting that Doyle’s creativity is proportional to the emotional intimacy of the material.

One might say that Endless Poetry could use more Jodorowsky. Much of the movie deals with the Alejandro character’s misadventures with the other literary figures of the time, including Díaz, the poets Enrique Lihn (Leandro Taub) and Nicanor Parra (Felipe Ríos), and the journalist Maria Lefevre (the storied choreographer Carolyn Carlson, making her acting debut), who introduced Santiago’s arts community to tarot and the occult—lengthy episodes that lack both the surprising emotional candor and the quick surreal wit that distinguished The Dance Of Reality, preferring a more theatrical variety of symbolism. It still provides some spots of memorable, grotesque imagery: the dictatorial, right-wing former (and future) Chilean president Carlos Ibáñez Del Campo returning from exile aboard a life-size cardboard cutout of a train; a parade of skeletons and a parade of red devils blending together at a forked intersection; stagehands in full-black ninja suits creeping around the corners of the Jodorowsky household; the appearance-obsessed Jaime refusing to acknowledge an earthquake as the walls crumble around him. But there’s the old problem with making yourself the center of your art: You can become your own tough act to follow.