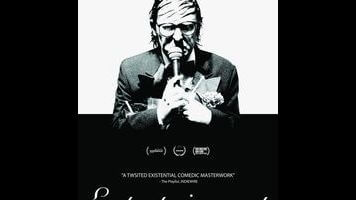

Entertainment gives Neil Hamburger the alienating star vehicle he deserves

Neil Hamburger, the stand-up comedian created and played by Gregg Turkington, is designed to repel. For two decades, Turkington has been perfecting every deliberately off-putting detail: the halting, abortive delivery; the moist mop of hair, drenched in flop sweat; the constant throat-clearing, the punctuating of crass punch-lines with a glob of nervous phlegm. And that’s to say nothing of the jokes themselves, the nasty question-and-answer celebrity zingers. (Sample gag: “What do you get when you cross Sir Elton John with a saber-toothed tiger? I don’t know, but you better keep it away from your ass.”) Of course, by now, Turkington has released enough albums and made enough talk-show appearances to have earned a loyal following among comedy nerds hip to his shtick; those who actually go to a Neil Hamburger show know what to expect. They’re in on the joke.

Entertainment, the new film from writer-director Rick Alverson, runs with a hypothetical scenario: What if Turkington-as-Hamburger were to take his show on the road and play only the tiniest, most hole-in-the-wall venues in Southern California, to sparse and hostile crowds of people not in on the joke? Furthermore, what if the antagonism his routine deliberately provokes brought him no satisfaction whatsoever? Entertainment drags this lightly fictionalized version of Hamburger—he goes by Neil on stage and off—through a gauntlet of failure, watching as he hacks and wheezes out vulgar one-liners to increasingly small, increasingly unresponsive dive-bar audiences. It’s a portrait of the comedy tour as odyssey of madness, a plummet into the abyss.

Alverson has been down this road before. His previous film, The Comedy, cast Tim Heidecker (of Tim & Eric fame) as a hipster dirtbag who shielded himself with a heavy coat of irony and offensive humor. It’s still tough to say whether the film was intended to be a genuine examination of generational detachment or an advanced put-on parody of the same. Entertainment, which the director wrote with Heidecker and Turkington, does for the latter exactly what The Comedy did for the former—namely, interrogate his specific kind of anti-comedy, finding a layer of deep melancholy beneath it. If it can be believed, it’s an even less approachable movie, but also a more singular one: Alverson has fine-tuned his own antagonistic style, caught somewhere between the driest of desert-dry humor and the existential terror of a bad dream.

Beginning with a gig at a prison—his most receptive audience, by far—Hamburger winds his way back to Los Angeles, hitting various nowhere joints along the way. (His opener is an oddball clown, played by Tye Sheridan, whose very loose, slapstick routine always seems to go over a little better with the locals.) Hamburger’s act is often scandalously funny, and whenever Alverson is lingering on the comic as he bombs spectacularly or viciously silences hecklers, the film gains a confrontational power. But the performance scenes make up only a fraction of the running time, which is otherwise filled with long, languorous passages of Hamburger “out of character,” as he takes scenic drives through the desert, makes sad and unanswered phone calls to an unseen daughter, and fails to connect with the estranged, businessman cousin (John C. Reilly) who briefly puts him up.

Alverson has an eye for the barren grandeur of the Southwest. Entertainment is a road movie, and it’s hard not to think of Wim Wenders whenever Turkington is behind the wheel of a car, stopping to sightsee at a shooting location from Five Easy Pieces or to study the wreckage of an ancient car crash. But whereas Wenders saw awe and mystery in the American landscape, Alverson detects a mounting dread: There’s plenty of David Lynch, too, in his vision of a ghost-town California, where every dingy motel plays the same nightmarish Mexican soap opera, and the ambient drone of the soundtrack, buzzing like a didgeridoo, hints at a horror creeping just beyond the frame. As if to mark the intersection of these two directorial influences, Alverson casts Dean Stockwell in a wordless cameo, his poolside presence conjuring the ghosts of Paris, Texas and Blue Velvet. He also makes Michael Cera menacing—no small feat.

Entertainment is hypnotic and distinctive enough to make you wish it had a few more tricks up its sleeve. The venues get smaller, the phone calls home become more desperate, and the encounters with strangers grow more surreal, but the film never shifts gears; it hits the same note of deadpan despair over and over again, until shock begins to calcify into boredom. The Comedy had a clearer sense of purpose; here, Alverson seems to be riffing on little more than the conventional wisdom that comedians are sadsacks at heart, and while the circular repetitiveness of the film’s structure may accurately convey the grind of life on the road, it doesn’t entirely excuse the general tedium that begins to set in. Yet Entertainment is too artful in its aggressive alienation tactics to outright dismiss. Like Hamburger himself, the film seems engineered to polarize. But even those left confounded or enraged should know a unique experience when it slaps them, in the comedian’s own parlance, straight across their fool faces.