Esad Ribić showcases Conan’s primal appeal in his fully painted Exodus

When it comes to pure masculinity, few characters match Conan The Barbarian. He’s a huge, preternaturally strong warrior who rises from rogue to king, driven by hunger for gold, women, and power but still maintaining a noble spirit. He’s one of those iconic genre figures that sets the template for a certain type of hero, but in the new Conan The Barbarian: Exodus one-shot, Esad Ribić reveals a period before Conan had assumed his fearsome barbarian persona. Written and painted by Ribić with letters by Travis Lanham, Exodus details 15-year-old Conan’s first journey away from his home in the frozen mountains of Cimmeria, discovering the dangers of nature and the even greater threat of human civilization.

I’ve enjoyed Conan comics in the past, but I don’t have any deep affinity for the property. I appreciate the role Conan plays in comic-book history, keeping the pulp fantasy tradition alive as other genres rise and fall from popularity. In terms of genre coverage, Marvel Comics is back to where it was in the late ’70s and early ’80s, when it had its central superhero line along with Star Wars for sci-fi adventure and Conan The Barbarian for sword and sorcery fantasy. But while Star Wars has remained at the forefront of pop culture for decades, Conan hasn’t had the same staying power.

Marvel’s trying to revitalize interest in the character by putting the big-name creative team of Jason Aaron, Mahmud Asrar, and Matthew Wilson on the main Conan The Barbarian title, relaunching Savage Sword Of Conan as an anthology, releasing multiple Conan one-shots and miniseries, and integrating Conan into the Marvel Universe with Avengers: No Road Home and Savage Avengers. Time will tell if all this investment in Conan pays off—sales are solid for the ongoings and collections are selling well—but it’s easy to see interest in these books fizzling out if Marvel doesn’t put enough creative muscle behind them.

Conan was introduced in prose stories, so writers of Conan comics typically include a lot of narration in their scripts, taking advantage of the opportunity to use more heightened fantasy language. This creates consistency across different Conan creators, but also sameness. Conan: Exodus stands apart from the rest by doing away with almost all text. There’s no narration, and the few lines of dialogue are written in an untranslated runic language. Conan doesn’t speak, moving through the world like an animal that is solely interested in survival. That means taking out predators, so when Conan sees soldiers abusing villagers, he steps into a hero role to protect the weak.

As the cover artist on Conan The Barbarian, Esad Ribić channels classic Conan artist Frank Frazetta with his striking paintings each month. Exodus is also fully painted, and after years of seeing Ribić’s linework colored by others, it’s a pleasure to have him show off his mastery of shadow and light by painting his sequential art. Whenever I see an artist’s signature on a page, I’m always compelled to spend more time on it because there’s something that compelled them to put that extra stamp. Most of the pages in Exodus are signed, and because there’s almost no text, each page comes across as an individual piece of fine art.

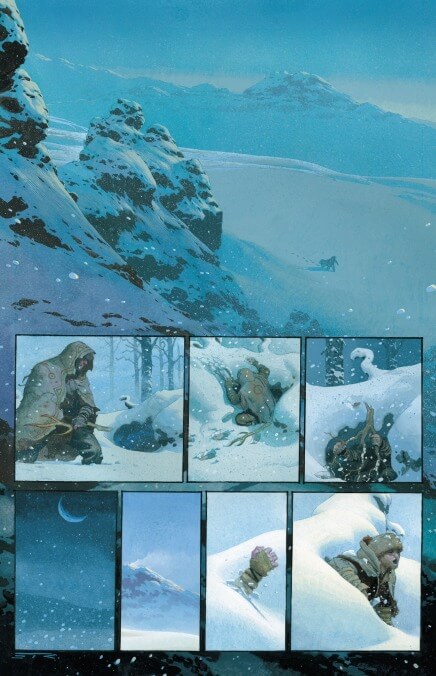

Take the time to look at the full page and absorb that slice of the story on its own. Without text, Ribić’s plot relies on Conan’s dynamic with the world around him to create an emotional throughline. The book opens with a mix of isolation and desolation as it shows Conan emerging from the snow-covered mountains on his own, surviving through the night by insulating himself inside a hole in the ground. The first page emphasizes the importance of the setting with a first panel that extends down the length of the entire page, expanding the scope of the mountain range by layering panels on top of that one landscape shot. It’s the only instance of a full-page bleed in the entire issue, presenting Conan as a small seed in a vast landscape that will grow to take control of his surroundings.

The first time we see Conan’s face, it’s a moment of surprise that reinforces the character’s youth with wide eyes and a slack jaw as he encounters his first threat in the wild. His face and spirit take damage that results in a drastically different close-up by the end of the issue, when he glares at the reader with brows furrowed, jaw clenched, and streams of blood pouring from his broken nose. The standalone stories of these initial pages impart important lessons on Conan as he learns how to navigate a lethal environment. On the page where he first encounters a wolf, he’s able to kill his first opponent, but then he’s chased down by two more, teaching him that there’s always a bigger threat around the corner.

Conan goes on an intense character journey in this one-shot, but Ribić presents it all nonverbally. It doesn’t take long for Conan to realize that he needs to project an intimidating, aggressive energy at all times or he’s going to be considered prey. When Conan encounters a bear at a watering hole, any trace of fear is gone. He’s actually excited, flashing a giant grin as he chucks his spear into the animal’s flesh. That sense of joy gives way to something more sinister when Conan jumps on the bear and starts stabbing it to death. Ribić tightens up on Conan’s face as he gazes intensely through a spray of blood, showing a major mental shift without using any words to get inside his head.

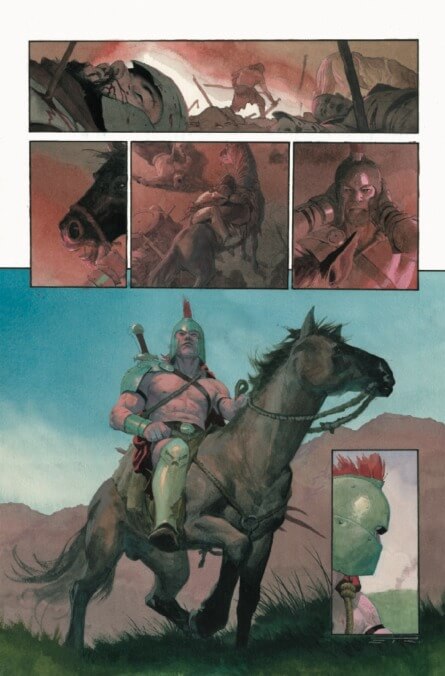

This new bloodthirsty mindset is the one Conan needs to survive in the world of man. After his encounter with the bear, Conan stumbles across a battlefield littered with dead bodies, which he pilfers for weapons and armor. This is where Exodus takes a tragic turn, and as Conan ventures deeper into society, he discovers that it’s even more dangerous than the wild. There’s sadism behind this predatory behavior, and after standing up to an oppressive force, Conan is strung up and left to die. The mistake is that he’s not executed right away, and when Conan breaks free, he reaches the final stage of his bloody exodus.

Strung up on two poles, Conan looks out toward the room where his tormenter sleeps. The man will not make it through the night. This isn’t the kind of kill that happens in the wild when Conan is looking for food while trying not to become an animal’s meal. This is murder, an act of vengeance against someone who made Conan suffer. The composition of the shot revealing the dead body intensifies the brutality with the dark red blood seeping into ivory bed sheets, marking a stain on Conan’s soul as he takes a human life. Gone is the boy ambushed by a surprise enemy, replaced by a barbarian always on alert, ready to destroy anything that stands in his way.