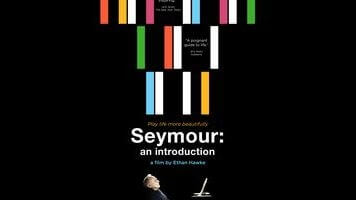

Ethan Hawke pays tribute to a great teacher in Seymour: An Introduction

J.D. Salinger fans will be given pause by the existence of a movie called Seymour: An Introduction, as that particular story—a tortured swirl of self-conscious verbiage—is perhaps the least adaptable piece of fiction the author ever wrote. Thankfully, Ethan Hawke, directing his third feature (following Chelsea Walls and The Hottest State), has merely borrowed the title for this documentary portrait of Seymour Bernstein, a mostly retired concert pianist and still-active music teacher. Hawke and Bernstein met by chance at a dinner party a few years ago, instantly developing a rapport; Bernstein’s philosophies regarding art and life helped Hawke overcome a recent battle with crippling stage fright, which is perhaps why the actor-turned-director felt they deserved a wider audience. His instinct regarding Bernstein was sound—the octogenarian makes a compelling camera subject. Hawke’s instincts as a documentary filmmaker, however, are still a bit shaky.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.