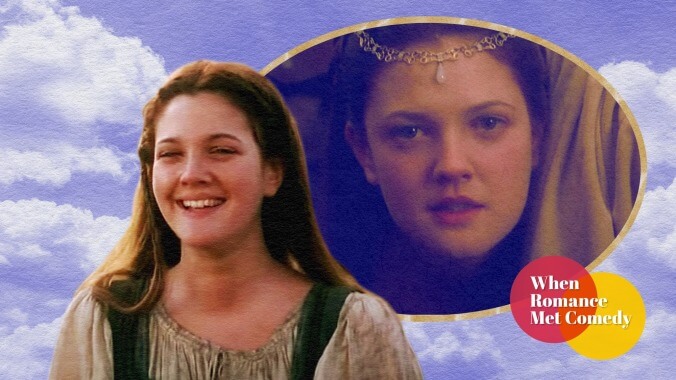

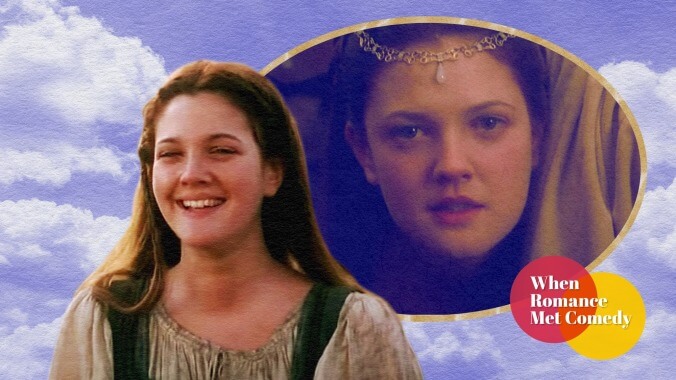

Ever After did the Cinderella story right

In 1998, Drew Barrymore added a refreshing moral backbone to the classic princess fairy tale

Image: Graphic: Libby McGuire

Between a splashy new Andrew Lloyd Webber musical on the West End and a flashy new movie musical starring Camila Cabello, Cinderella is having a bit of a moment. But then again, when is she not? The age-old folk tale has been told, retold, and remixed so many times that there’s a Cinderella for every era and every mood—from the iconic 1950 Disney animated film that pulled from 17th-century French writer Charles Perrault to shape our modern-day image of the fairy tale princess, to modern riffs like Ella Enchanted that try to upend it. Our shared pop culture lexicon has landed on Cinderella as the ultimate symbol of conventional femininity, which, of course, makes her beloved and despised in equal measure. She’s the princess against which all princesses are compared—and to some degree the woman against which all “girl culture” is shaped.

And nowhere was that clearer than during the 1990s. Between a rom-com resurgence that kicked off with a sexy, contemporary Cinderella update in Pretty Woman, and a Disney animation renaissance filled with plucky princesses who were largely defined by the ways they weren’t Cinderella, our image of the little cinder girl was challenged and reshaped during the “girl power” era. And those cultural trends came to a head in Ever After, the wonderfully whimsical 1998 historical romance that cast Drew Barrymore as Danielle de Barbarac, a self-possessed Renaissance-era Frenchwoman the movie imagines as the “real” inspiration for the classic fairy tale. With a few savvy adaptation choices, Ever After managed to deliver an empowered take on Cinderella without throwing the storybook beats under the bus. It’s a sparkling balancing act that few other adaptations have been able to match.

The project started with future Erin Brockovich screenwriter Susannah Grant, who was then coming off working on Disney’s Pocahontas. Commissioned to write a version of Cinderella with a “Merchant-Ivory feeling to it,” Grant decided that rather than deconstruct the classic fairy tale, she wanted to “reconstruct it” with a historical bent that took out the magic and subbed in a rational romanticism characterized by using Leonardo da Vinci as the fairy godmother. Updating the story’s gender politics was, to some degree, incidental. Asked whether she purposefully wanted to create a more self-reliant Cinderella, Grant replied, “I’m not sure that was conscious—it may just not occur to me to come up with characters who can’t take care of themselves.”

Regardless, it was the logline “Cinderella rescues herself” that caught Barrymore’s eye. The twentysomething was looking to reshape her career, which had up until then been defined by child stardom, tumultuous personal problems, and a series of Lolita-style bad girl roles. Not only would playing Cinderella be a reset of her public image, Barrymore felt deeply connected to the story of a young woman who uses her own strength and tenacity to pull herself out of a toxic childhood and into a fairy tale happy ending. (“Drew had lived Judy Garland’s life by the time she was 12 and had gotten to the other side by the time she was 14,” director Joel Schumacher once put it.) Barrymore brought the project to Andy Tennant, who’d directed her in the 1993 TV movie The Amy Fisher Story. And they worked with Tennant’s writing partner Rick Parks to further tailor the script, making Danielle a little more of a rough-and-tumble tomboy and adding a subplot with some jovial Romani bandits.

Rewatching Ever After today, it’s still fun to watch Danielle wield a sword against her would-be captor or literally carry her prince to safety. But those moments of physical prowess actually stand out less than the way the film thoughtfully updates the moral cornerstone of the classic Cinderella story. One of the best pieces of cultural criticism of the past few years is a video essay from The Take that revisits Disney’s animated Cinderella and challenges our loosely shared assumption that it’s a story of a weak, passive woman who’s rescued by a prince thanks to “pure dumb luck and a pretty face.” The Take reframes Disney’s Cinderella as the tale of a woman who chooses radical kindness and compassion in the face of abuse and oppression—something the 2015 live action remake phrased as the motto “have courage and be kind.” Cinderella’s greatest strength is mental, rather than physical. Hers is the story of finding a way to maintain your humanity even in difficult circumstances you’re powerless to change. And in a world where life sometimes sucks in ways you can’t simply fight your way out of, there’s a strength to presenting that kind of fairy tale for kids too.

But whereas most adaptations demonstrate Cinderella’s inner fortitude through her pleasantly sunny demeanor and kindness toward animals, Ever After expands it into something more active and three-dimensional. Long before Danielle rescues herself, we see how far she’ll go to rescue other people. Early in the film, she disguises herself as a noblewoman to buy the freedom of a fellow servant that her stepmother (Anjelica Huston) has cruelly sold to pay off her debts. It’s a plot point that sets up Danielle’s mistaken-identity romance with Prince Henry (Dougray Scott), who assumes she’s a mysterious visiting courtier. But it’s equally a character beat that demonstrates Danielle’s bravery, compassion, and commitment to social equality. Not only does she get the prince to help her reunite her household, she inspires him to end indentured servitude as a practice altogether.

Like Dirty Dancing before it, Ever After is a romance that’s first and foremost about moral values. “A servant is not a thief, Your Highness, and those who are cannot help themselves,” Danielle tells the dashing but immature royal before quoting Thomas More: “If you suffer your people to be ill-educated and their manners corrupted from infancy, and then punish them for those crimes to which their first education disposed them, what else is to be concluded, Sire, but that you first make thieves and then punish them?” Henry falls for Danielle because of her passion and conviction, while she’s drawn to him because he not only listens to her, but changes his mind based on what she has to say. In this telling of Cinderella, the heroine’s dream isn’t just to marry a prince, it’s to reform his kingdom into a socialist utopia in the process.

Ever After offers the same mix of swashbuckling fun and social justice theming as Errol Flynn’s The Adventures Of Robin Hood, only with even more of a feminine, feminist focus. Yet the lesson never feels didactic because Tennant wraps it all up in such a whimsically engaging package. Ever After is structured more like a rom-com than a fairy tale, with extended scenes of Danielle and Henry’s courtship that makes their love story feel earned. (In this version, Cinderella goes to the ball not to meet the prince, but to reveal her true identity to him.) Scott, in particular, has a lot of fun leaning into the Shakespeare In The Park-lite of it all, with a spirited, floppy-haired gusto that sells the flirty oil-and-water romance. “Why do you like to irritate me so?” Danielle sighs. “Why do you rise to the occasion?” he winkingly responds. And what Barrymore lacks in a consistent accent, she makes up for with a beautifully openhearted emotionality and a great face for the Renaissance.

Ever After also understands that the Cinderella story is as much about toxic family as it is romance. Though the film never softens stepmother Baroness Rodmilla de Ghent’s villainy, it contextualizes the social forces that have shaped her into who she is, including the way women of the era were forced to rely on marriage as their main source of economic support. More so than any other adaptation I’ve seen, Ever After foregrounds the horror of the fact that the Baroness is a widow with two young daughters who uproots her entire life to marry a man who then almost immediately dies in front of her. (A death punctuated by an incredibly effective use of a dolly zoom.) Watching the Baroness scream “You cannot leave me here!” at her new husband’s body is genuinely wrenching, and Ever After maintains a subtle through line about the way that trauma shapes her mistreatment of her stepdaughter. The benefit of casting an actor as skilled as Huston is that she can play complex, conflicting emotional layers in between tossing off archly campy villain lines like, “Darling, nothing is final until you’re dead—and even then I’m sure God negotiates.”

Ever After is also smart about the way that hierarchies of cruelty are learned. The Baroness was taught cutthroat social climbing from her obsessive mother and is now passing it along to her own spoiled, arrogant daughter Marguerite (Megan Dodds, whose every line reading is a gift). But the movie finds hope in the idea that those hierarchies can be unlearned too—like the way put-upon stepsister Jacqueline (Melanie Lynskey) slowly starts to shift her moral compass in Danielle’s direction. It’s a nice extension of the film’s ethos that people can change, not to mention a smart way to get a little more female solidarity into a Cinderella adaptation that recasts the fairy godmother as a male artist-inventor.

Ever After also delivers a complicated answer to the question of why its Cinderella figure doesn’t simply leave her abusive environment. Part of it is because Danielle feels connected to her father’s manor and the people that work there; part of it is because she doesn’t really have anywhere else to go; and part of it is because she feels a complicated sense of loyalty to the only family she has left, cruel as they may be. Barrymore is great at playing the raw emotional yearning that characterizes so much of Danielle’s life. It was another personal point of connection for the actor, who explained in a 1998 interview, “I’m closer to my parents now, but no one in my family is really going to be there for each other. It’s too late. I thought about whether I wanted to be a really resentful person, but it’s just poison and you just have to let it go. I love them and I hope they’re proud of me, but none of us can really tolerate each other. But that’s cool. A lot of families are like that.”

Part of the reason the Cinderella story has endured is because the difficulties of its heroine’s life are so relatable—in the same way that’s true of comic book heroes like Peter Parker or Steve Rogers, both of whom have elements of Cinderella in their DNA. And when we dismiss “princess culture” as a whole, I think we’re underestimating young people’s ability to enjoy the beautiful ballgowns and handsome princes while still finding deeper emotional resonance to these stories too. What’s great about Ever After is that it updates the Cinderella story without scoffing at its fairy tale origins. A framing device featuring legendary French actress Jeanne Moreau lends welcome gravitas, but part of the self-aware fun of Ever After is that its worldbuilding feels as much like a theme park as a realistic take on 16th century France. Like Shakespeare In Love, which came out the same year, Ever After is unembarrassed to be an earnest, playful historical romance, which is a style of movie that seemed to quickly fall out of fashion in the more cynical aughts.

It’s that unabashedly wholesome tone that ties Ever After to the late ’90s as much as Danielle’s body-glitter-heavy look at the masquerade ball. Yet there’s a timeless quality to Ever After too, largely because its themes remain so relevant. Barrymore still cites it as one of her favorite projects, particularly because of the way it empowered her to take more control over her own career. (She launched her Flower Films production company the next year.) And along with the Brandy/Whitney Houston TV musical from 1997, it’s one of the best live action Cinderella adaptations out there. Critics and audiences agreed at the time. Ever After made $98 million worldwide and currently sits at a 91% on Rotten Tomatoes, although it’s been a little bit forgotten by the larger culture since then—at least by those who weren’t the right age to make it a sleepover favorite. Still, with Cinderella in the zeitgeist once more, it’s an ideal time to try this effervescent adaptation on for size. As a crown jewel in the canons of both rom-coms and princesses, Ever After has a soul (and a sole) all its own.

Next time: Twenty years ago, Mira Nair’s Monsoon Wedding served up a different kind of wedding comedy.

GET A.V.CLUB RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Pop culture obsessives writing for the pop culture obsessed.