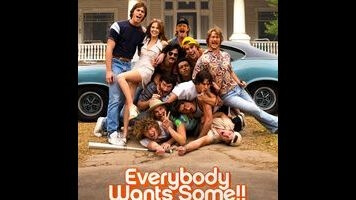

There’s little room for villains in a Richard Linklater film; when the guy throws a party, even the assholes make for good company. Which is fortunate, because for a little while, just about every character in Everybody Wants Some, Linklater’s new timewarp of a hangout movie, comes across a bit like a douche bag. When we first meet the boys, a hard-drinking college baseball team living under one (slowly collapsing) roof, they’re behaving like the jocks of any old campus comedy: chasing skirt, hazing freshmen, and bonding through a never-ending Olympics of macho competition. They’re frat brothers in all but name, and a non-pledge might seriously wonder if they really want to spend two hours in a kegger simulation, but without a buzz on. Eventually, though, something strange and almost magical happens: Personalities start to form, banter starts to land, and—against all odds—this jovial broletariat starts to actually grow on you. That’s the Linklater touch. He makes open-mindedness infectious.

From “Heart Of Glass” to Space Invaders, Linklater keeps the late-’70s/early-’80s signifiers coming. But he doesn’t just want to yank audiences back to the intersection of two eras. He wants to put his own spin on the post-Animal House slobs-vs.-snobs yukfests of that time period, only without the snobs, the “versus,” or any of the stuff—plot, drama, conflict—that might harsh the good-times mellow. Our ballplayer heroes, who spend all of a few minutes on the field, are a colorful posse of alpha jokesters: the swaggering team captain (Tyler Hoechlin), firing insults from behind a then-fashionable porn ’stache; the quipster ladykiller (Glen Powell) who’s pioneered his own pickup science; the resident pothead (Wyatt Russell) who’s as much into Carl Sagan as girls and sports. But most of these guys, for all their relentless pleasure-hunting, have genuine philosophies about the world (when does a Linklater character not?), and as the movie’s endless chatter diversifies, Everybody Wants Some reveals a stealth humanism: Shoot the shit with anyone for long enough and they reveal hidden depths.

Our window into this laidback dude-bro bacchanal is Jake (Glee’s Blake Jenner), the team’s sweet, even-keeled freshman pitcher; he’s like a more athletic version of the final-larval-stage Mason we see at the end of Boyhood, or Jason London’s graduating quarterback in Dazed And Confused, rebooted as the low jock on the totem pole. (Funny how college acts like a great equalizer, knocking teenage royalty back to the bottom of the social pecking order.) Jake, who Linklater grants a kind of miniature Before Sunrise with the quirky theater girl (Zoey Deutch) he meets on day one, has the perpetual grin of someone getting his first taste of the college bubble, that free zone between the restrictions of childhood and the responsibilities of adulthood. If he’s not the most dynamic protagonist, that’s because the kid’s serving as proxy for both the audience and the filmmaker: Linklater played baseball in college, too, and Everybody Wants Some, which he shot on some of his old Texas stomping grounds, has the faint glow of nostalgic autobiography, like a fond memory stretched to feature length.

Describing a favorite band after an enormous bong hit, Russell’s stoner sage praises their ability to “find the tangents within the framework.” That’s a good assessment of Linklater and his casually poignant gabfests; the guy’s all about tangents. In Everybody Wants Some, whose title officially comes affixed with two emphatic exclamation points, Linklater gets you hooked on the numbskull rituals—the pranks, the instant camaraderie, the private games (like spotting the disguised big-league scout watching them practice from afar)—of these fast and loquacious friends. Over the course of three eventfully uneventful days, the team never stops shedding uniforms, as they party hop from a disco bar to a country saloon to a punk club. “It’s not phony,” one of them protests when Jake expresses his embarrassment about their ability to infiltrate any culture. “It’s adaptive.” Linklater is interested in that moment, in the early ’80s, when pop culture started to splinter into a million different directions. But he’s also smart enough to recognize that as rapidly as fashion and music were changing, the basic pursuits of young dudes—getting drunk, getting laid, living completely in the moment—remained more or less the same.

For all its effortless good humor, Everybody Wants Some doesn’t achieve the pure pleasure high of Dazed And Confused, in part because it limits its focus to just one group, the golden-boy athletes, instead of offering a whole social spectrum. Even that, though, reflects Linklater’s we’re-all-just-people perspective. In college, cliques stop mattering as much, and the walls separating different scenes start to crumble, as when our easygoing meathead heroes crash a drama-club party and start mingling with the performing-arts kids. All the characters, from Jake to his new teammates to his nerdish crush, are adjusting to the transition from a little pond to a big one; now that they’re no longer the brightest stars of their community, they have to start defining themselves through something other than their interests and talents. They have to become someone. In its funky, aimless, winningly juvenile way, Everybody Wants Some is about as inclusively celebratory as any college comedy in memory: Per its title, it really does want everybody to get some.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.