Everything looks like the end on Halt and Catch Fire

(No rational person reads a review before watching the episode and then complains about it, but here’s your one spoiler warning for “You Are Not Safe.”)

“You Are Not Safe” isn’t the end of Halt And Catch Fire, but it certainly could be. Not just because of what Ryan does tonight, although the voiceover of his suicide note at the end of the episode sure sounds like a eulogy for the series.

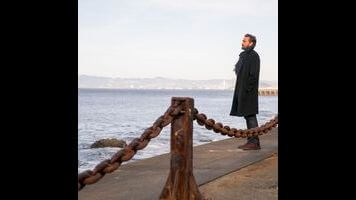

The montage there is of shattered, disillusioned people. Joe, walking the shore where we first saw him surfing confidently, is wrapped up in heavy clothes (even though someone’s surfing contentedly) and contemplating what he’s done, and what he does now. Bos and the coders—dealing with the double blow of Ryan’s death and the crushing failure of the IPO they thought was going to make them rich—sit silently around the Mutiny office, Ryan’s online suicide note on every terminal. Gordon, perhaps in the best position of the group, considering that Joe’s withdrawal from their joint venture frees him to pursue the NSFNET deal, must now cope with Donna’s disappointment, and a marriage shaken by Donna’s recent actions. (Adding to the stack of problems in the Clark marriage.)

And Donna and Cameron—locking eyes in the supermarket before waving a hollow hello—are done. Donna’s dream of leading Mutiny to multimillion-dollar success—for which she sacrificed her friendship with Cameron—is at least critically wounded. (Bos estimated that their stock would open at 15. We see it open at 6, and it starts immediately falling.) And Cameron, happily accepting the hugs from Donna’s daughters (Cam always was the cool aunt/older sister) is only there to buy sundries for her move to Tokyo with Tom. Whatever Mutiny was, it isn’t now. And whatever hopes these people had of reaching somewhere together look dashed, completely.

And Ryan is dead, having thrown himself off of Joe’s balcony once he realized, irrevocably, that his dreams were dead, too. Manish Dayal has often seemed lost as Ryan, a purely reactive hothead with predictable verbal tics and too little agency. In the end, though, Ryan’s shocking death makes sense just because of how little there was to him. The first time we saw him listening to Joe’s slickly messianic “Are You Safe?” pitch, Ryan was enraptured, beaming in something like awe. Ryan Ray was, in the end, looking for someone to believe in—and to follow. His frustration at Mutiny sprang from the fact that, while he saw Cameron as a possible leader, she wasn’t interested in being one. (Or interested in putting up with his often brusque way of expressing himself.) Joe, collector of worshippers—like season one Gordon—saw both Ryan’s brilliance and his unformed neediness, and he played his usual Joe MacMillan games for what he assumed was mutual benefit.

“You’re a master at this kind of move,” rants Ryan on the night before his suicide, “It’s classic Joe MacMillan!” Joe, rattled and at a loss for how to help Ryan undo the damage he’s done to his future, can only reply, “I can’t work with Joe MacMillan any more.” It’s of a piece with what he says to Gordon later, as he pulls out of the NSFNET plan (which, in real life, essentially helped birth the internet as we know it). “Jesus Christ. I was trying to help him. I can’t keep having this conversation. I’m done.” For everyone waiting for Lee Pace to finally be free of having to embody Halt And Catch Fire’s antihero figure, this is the scene. Pace, stripped of Joe’s usual, manufactured persona, is simply human—and bereft. When he stops Gordon for a moment and says, earnestly, “Gordon, I’m sorry,” Pace makes Joe’s apology an all-encompassing one. Joe, walking alone by the ocean at episode’s end, Ryan’s dying words in his mind, has no more moves to make, and no desire left to make them.

In Ryan’s parting words, there are clues to why he’s done what he’s done. Crafting a warning about what he envisions the coming online world is going to mean, there’s that hint of that unformed, dangerously idealistic passion in his talk of placating bedtime stories and his overdramatic, “Beware, baffled humans.” There was something missing in Ryan that set him on a quest to locate the one person who could make him feel safe, in spite of all his undeniable brilliance. Ryan was most likely better than Cameron technically (certainly better than Joe, with his self-taught C++), but he couldn’t tell himself the bedtime story he needed to keep his fears away.

Suicide as a plot device can be an irresponsible and cheap trick. But, in Lisa Albert and Alison Tatlock’s graceful gut-punch of a script, Ryan’s action doesn’t feel manipulative. Halt And Catch Fire, at its best, has been about its characters knowing in their bones that they’re onto something important, and fumbling forward in pursuit of it. As the show’s gone on, some of the most thrilling scenes have been powered by the joy and excitement of discovery, of hands-on problem-solving in service of imagination, and hope. In Ryan’s speech, the writers are sending their own call out to a world where the interconnectivity of Ryan’s warning has become commonplace—as have its dangers and unthinking, unthinkable indignities.

The barriers between us will disappear. And we’re not ready. We’ll hurt each other in new ways. We’ll sell and be sold. We’ll expose our most tender selves only to be mocked and destroyed. We’ll be so vulnerable, and we’ll pay the price.

Everyone on Halt And Catch Fire, even touching only the barest edge of the oncoming wave of this new form of communication, is wounded by it. Donna’s dream of following Diane’s example as an independent businesswoman ignored the pill bottles on Diane’s dresser and Diane’s estrangement from her family. (Gordon and her daughters can barely be bothered to talk to her on the phone from her swanky hotel suite.) She rushed ahead, sacrificing her best friend to do it, and got swatted back, her final scene tonight seeing her back to pushing a shopping cart with her daughters, waving a hopeless goodbye to the woman who actually understood her best. And she wasn’t even wrong, necessarily—as her discouraging interview with a condescendingly vapid news anchor on the eve of the IPO showed, she was battling ignorance, and sexism. (The anchor assumes Mutiny founder Cameron Howe must have been a man.) But being ahead of your time means being isolated in your time.

Cameron rattles around her house all day, watching game shows and the buzzing wasp’s nest on her porch with equal, disconnected fascination. Her marriage to the loving but worried Tom isn’t a bad idea in itself (even Joe, come to ask for her help in locating the on-the-lam Ryan, ruefully admits Tom’s a good guy). But Mackenzie Davis keeps finding ways (a pause before answering a question, averted eyes) to indicate that, perhaps, fleeing to marriage with Tom was at least partly fleeing from something else. It’s a touching surprise (although partaking of that same need for escape) how ready Cameron is to follow Tom on his promotion to Japan. (“That’s perfect.”) And the video game she invents, about a kickass adventurer on her space-motorcycle in quest of goals like a sense of proportion, humor, self, common sense, and decency (the key to everything in the game), is so achingly self-aware and sweet that, caveats aside, it makes it look like she and Tom might make it work.

Some have complained, not without reason, that seeing the protagonists of Halt And Catch Fire be at the forefront of almost every technological advance from the show’s time period is unrealistic. I get that. But this is a show about people who see the nigh-infinite promise of what was merely another appliance to much of America—and see their own dreams there. Watching Donna, Gordon, Cameron, and Joe—and Ryan—pursue the distant, indistinct glimmer of connection, of innovation, of self-fulfillment in their vocation has been as exhilarating as watching their failures has been heartbreaking. It’s a show about chasing dreams inside a machine.

Ryan cites the danger of corporations, bad teachers, and corrupt leaders, but, as this series has shown again and again, the real danger is from each other, and ourselves. As we find new ways to reach out, we open ourselves to new ways of being hurt. His suicide note ends, with a note of touching hopefulness:

It’s a huge danger. A gigantic risk. But it’s worth it. If only we can learn to take care of each other. Then this awesome, destructive new connection won’t isolate us. It won’t leave us, in the end, so totally alone.

Everyone at the end of “You Are Not Safe” is, essentially, alone. As I said, this seems like an ending. With two episodes left in the season (possibly the series, ratings considered), and with Ryan’s plea echoing in the characters’ heads, the prospect of watching these people, somehow, try once more to find a way back to connection is absolutely fascinating.

Stray observations

- It’s to the writers’ and Kerry Bishé’s credit that Donna’s choice to oust Cameron isn’t presented as a villainous one. From the start, Donna (she and Gordon created their first machine together, remember) has understandably felt shunted to the side. With Diane’s example and encouragement Donna sees this move as her due, and Bishé’s face when the first notification of her failure appears on her computer screen is devastating. Diane’s well-meant “It doesn’t mean that the stock is worthless” is, itself, worthless to Donna. Alone, Bishé registers Donna’s wrenching bafflement with a series of little hand-jerks, as if she’s shorted out.

- Joe’s pronouncement that he’s done being “Joe MacMillan” is so shocking because comes an episode after his latest big play looks about to get the Joe and Gordon team back together again. Only their relationship is better this time, which makes it especially sad. Joe teasing the tongue-tied Gordon’s inability to ask if Gordon and Ryan were lovers is as natural and funny as Joe’s ever been. And his adamant refusal to let Gordon leave before he finds out the details of Gordon’s illness is as human.

- The Joe-Cameron scene is great, too, from Cameron greeting his Halloween visit with, “Well, it’s a very tall child dressed as Joe MacMillan,” to Joe’s “Batman was sold out.”

- Cameron’s watching the original Evil Dead, where you can just hear one of the deadites’ insidious “Join us!” coming from the screen while she talks to Joe. Only, Joe’s not looking for anything but help this time.

- Cameron to Ryan, after she tracks him down: “Joe can be surprisingly forgiving. Maybe its because he screwed up his own life so many times.”

- Ryan’s furious, “I’ve been out there since, defending your name!,” to Joe hints just how invested he is in Joe being the figure Ryan needs him to be.

- Bos, refusing to let Donna off the hook with her platitudinous speech about what Cameron meant to Mutiny: “It sounds like you’re eulogizing the family dog.”

- Her “She’s a temperamental narcissist with self-destructive tendencies who doesn’t work with others,” is more accurate, but not what Donna decides to go with.

- You just know Donna’s sunk when the vapid TV host cuts her off with, “Oh dear, it’s sounding complicated!” when Donna tries to explain what a modem is.