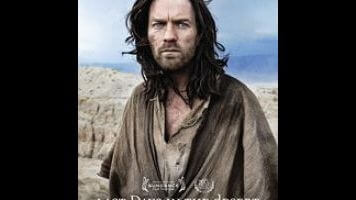

Yeshua (Ewan McGregor) heads out into the desert to fast and pray. The camera follows him as he trudges around, making a few pauses wherein he pleads for his father (or Father) to contact him. Eventually, he meets an isolated family whose mother (Ayelet Zurer) is dying and whose son (Tye Sheridan) wants to leave the desert for Jerusalem. The father (Ciarán Hinds) wants him to recommit to desert life after the mother has passed. That is more or less the full story of Rodrigo García’s Last Days In The Desert, which is inspired by the biblical passages mentioning Jesus Christ’s 40 days of prayer, during which he faces three temptations from Satan. García’s movie does not attempt to spin this material into its own legend or adapt some underappreciated corner of the Bible. Instead, it takes an opportunity to imagine Jesus as a person whose 40 days in the desert pass like actual, not symbolic, time.

Satan does appear here, looking exactly like Yeshua and also played by McGregor, but their conflicts appear more philosophical than mythical. McGregor plays the devil as a force who maintains a sort of disgusted fascination with God’s plans, disparaging the whims they must involve. In one of the movie’s very best scenes, he teases Yeshua with knowledge of alternate versions of the universe, which he claims has been repeatedly recreated so that God could, say, see plant leaves bend in a slightly different direction (it’s possible that Satan is exaggerating about God’s capriciousness). Rather than giving Jesus the full-court temptation, he lingers around to see where the desert-wandering goes, too confident to hype up his own seductive power. McGregor plays opposite himself skillfully, differentiating the two characters with as little as a facial expression.

Ultimately, it’s these scenes of Yeshua’s reflection—including the early, near-silent moments of McGregor traipsing through the desert on his own—that carry the most power. To capture the often breathtaking scenery, García has managed to capture cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki, breaking him out of his long-standing Terrence Malick/Alfonso Cuarón/Alejandro González Iñárritu cycle for only the second time in over a decade. (The only other filmmakers able to lure Lubezki away were the Coen brothers, for whom he shot Burn After Reading.) The camerawork here doesn’t have the same visceral kick as Lubezki’s other survival stories, transcendence journeys, or attempts at both, but as with the recent Malick movies, the camera movements stand in for the protagonist’s spiritual roiling.

This isn’t unusual for García, whose other movies (including Albert Nobbs, Mother And Child, and Nine Lives) often focus on internal struggle. But they can be talky pictures, too, and Desert’s family scenes play, at times, like an unplugged version of his more contemporary melodramas. Some of it is compelling, but García’s dialogue sometimes takes on strangely contemporary qualities (“Talk to him about something he’s interested in,” Jesus advises the father about his distant son). Sheridan, who has been so effective as various Texan kids in The Tree Of Life, Mud, and Joe, tamps down his Americanisms with such firmness that his performance goes stiff. At its worst, this stuff feels like ghostly allegory, even though it’s meant to be real.

As encouraging as it is to see a religious movie that doesn’t turn on an alternately cloying and fiery insistence that miracles, heaven, and/or God do factually exist, it’s hard not to wonder how much there really is to Last Days In The Desert. For a movie with very little action, it drifts by with the quickness of a dream, far from the grueling survival experience that could have been. It’s almost too delicate to offer much in the way of spiritual transportation; all it can do is deposit the audience at the end of the movie, 98 minutes later, with a tacked-on epilogue that brings the story to a familiar ending and, briefly, present day. By the end, what seemed like a lovely rumination starts to sound more like poetry refashioned as prose.