Ex Machina is smart sci-fi that loses its way

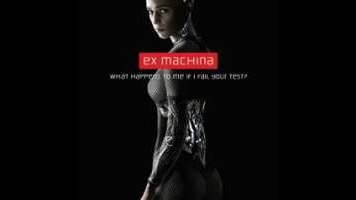

You can’t have consciousness without sex, says Nathan Bateman (Oscar Isaac), reclusive billionaire genius, as he sips Japanese beer on the top floor of his minimalist compound. Nathan, founder of search engine giant Bluebook, is a kind of hipster gym rat Dr. Moreau. He’s secluded himself here, to a private estate the size of a small country, to develop an artificial intelligence. Now, a Bluebook employee, Caleb (Domhnall Gleeson), has been flown over to test the AI, Ava (Alicia Vikander), a cutaway robot body that slinks and ticks and whirrs as she moves. With a lifelike face and hands made of synthetic skin, she resembles a wind-up doll stripped of its wig and clothing, the mechanism visible through her abdomen.

Nathan and Caleb think that they’re playing God, or maybe just Prometheus, and sure enough, like the fire bringer of Greek myth, Nathan is punished through his liver. Isolated and maybe lonelier than he admits, he gets blackout drunk every night and stumbles into his bedroom with the help of his perfect mute assistant, Kyoko. Of course, they aren’t really gods or even demigods. They’re men trying to make a woman. A fantasy woman, a dream girl—that is, the sum total of all of their anxieties, as enigmatic, alluring, and unpredictable as they imagine women to be. Maybe it’s subconscious; in all his years of trying, Nathan has never thought to make his AI anything other than female.

Ex Machina assembles this premise with a cleanness that brings to mind crisp speculative sci-fi prose, before taking an arbitrary left turn into the territory of corny slasher thrillers. In other words, it’s Sunshine all over again. First-time director Alex Garland wrote Sunshine and 28 Days Later for Danny Boyle, as well as the novel that was adapted into Boyle’s The Beach, which basically makes him a specialist in stories with rich ideas that are either undercut or canceled out by arbitrary endings. In that sense, Ex Machina doesn’t disappoint—or, rather, it disappoints in ways that are now predictable.

While Ex Machina’s ending isn’t unmotivated (the title isn’t foreshadowing, as much as a critic might want it to be), it does fracture much of what’s special about the movie. Up until the final scenes, Garland creates and sustains a credible atmosphere of unease and scientific speculation, defined by color-coded production design—neutral tones contrasted with the green of the woodland outside the compound and with bursts of eye-searing red during the occasional generator failure—and a tiny, capable cast. (Isaac and Vikander are especially good.)

Make no mistake, this is a film of ideas—sadder, quieter, more delicate than the Hollywood sci-fi standard—where every sliding wall of opaque glass suggests something about technology and the way people would use it. Ava is specifically gendered, but so is everything else in the film, from the friendship and tension that develops between the two men to Caleb’s unconcealed attraction to this demure robot, who lives in a little glass box with a closet full of floral print sundresses. In both his screenplays and his prose, Garland often focuses on makeshift societies; here, he creates a tiny one, limited to a few rooms and hallways, but with a future of infinite technological possibilities. As is often the case, it can’t fully let go of the world it’s supposed to replace.