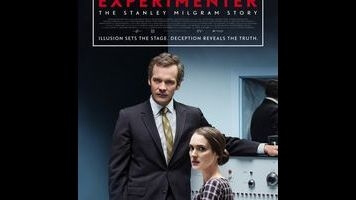

With his slightly reptilian gaze and carefully measured vocal cadence, Peter Sarsgaard makes an ideal Stanley Milgram in Experimenter, irrespective of any resemblance (or lack thereof) to the real-life Milgram. Milgram may well have been a warm, loving fellow who positively radiated empathy, but that’s not the impression that writer-director Michael Almereyda wants to convey. Rather, he enlists Sarsgaard to depict the popular notion of a scientist like Milgram, in order to explore fairly abstract ideas regarding ethics and objectivity. The film bears the subtitle The Stanley Milgram Story, but it’s most effective when it strenuously avoids biopic conventions, focusing intently on the man’s controversial professional life.

Wisely, Experimenter begins with Milgram’s most notorious series of experiments already in progress. Volunteers, unaware that they’re the true subjects, are told that a fellow volunteer (Jim Gaffigan) is hooked up to a machine that gives electrical shocks. They’re instructed to ask him questions, and to press a button that shocks him each time he answers incorrectly, with the level of the shock gradually increasing. In reality, the button does nothing; all of the man’s yelps and protests, emanating from a separate room, are feigned and prerecorded. What Milgram really wanted to find out was just how much pain people will willingly inflict if ordered to do so by an authority figure wearing a white lab coat. Repeatedly, he found that about 65-percent of his subjects would deliver what they believed to be a 450-volt shock, even after the man begged them to stop and then fell into a silence implying unconsciousness.

Reading about these experiments is disturbing enough, but it’s another thing altogether to see them convincingly dramatized. (The only previous attempt, it appears, was a 1976 TV movie, The Tenth Level, starring William Shatner as a fictionalized Milgram. A brief account of its making appears here.) The test subjects—superbly played by the likes of John Leguizamo, Taryn Manning, Anthony Edwards, and Anton Yelchin—exhibit a wide, complex range of behavior as they administer the shocks; most of them become highly distraught, asking to be allowed to end the experiment. Milgram rarely interacts with them directly (his assistants handle that), and Sarsgaard plays him as a man whose intense curiosity precludes any emotional involvement. He’s perfectly willing to shred people’s nerves in order to find out how atrocities like the Holocaust happened. If that detachment makes him seem a tad Mengelesque to some, oh well.

It’s all handled so deftly, and raises so many probing questions, that the film’s shift into more standard biopic territory in its second half can’t help but be a letdown. Early on, even briefly glimpsed aspects of Milgram’s personal life, like his relationship with wife Sasha (Winona Ryder), feel like extensions of his scientific method. And Almereyda—a hardcore formalist who once shot an entire feature on a PixelVision camera—reinforces that sense of artificiality throughout, having Milgram directly address the camera and staging several scenes in front of blatantly projected backdrops. But this surfeit of style, while invigorating, can’t disguise the fundamentally expository nature of the home-stretch material, which addresses various unrelated experiments (including one that would eventually inspire Six Degrees Of Kevin Bacon) and rehashes decades’ worth of arguments about whether the obedience experiments went too far. That’s something that viewers should judge for themselves, without being asked to take into account, for example, how Milgram’s early notoriety may have affected his subsequent employment prospects. The magnificence of the first half-hour or so, in particular, provides all the riveting context anyone needs.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.