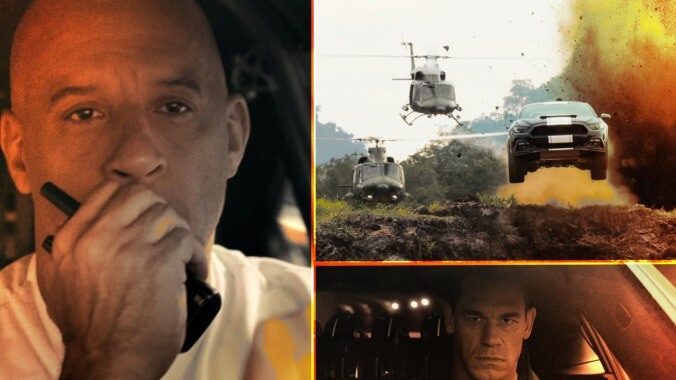

F9 got audiences back to theaters by giving them all the absurdity they craved

After a year inside, who could resist the siren call of Fast & Furious on the big screen?

Image: Graphic: Natalie Peeples

Early on in F9: The Fast Saga, the latest entry in the 20-year-old Fast & Furious franchise, there’s a scene where Tyrese Gibson’s Roman Pearce character survives a gunfight with a group of ill-defined Central American soldiers. When the smoke clears, Roman looks around in wonder, considering the implications of his own survival.

Shortly thereafter, a truck falls on Roman, and he walks away unhurt. Later on, he tries to tell Ludacris’ Tej Parker about what this might mean: “Think about this. We’ve now been on insane missions around the world, doing what most would say is damn near impossible. And I ain’t got a single scar to show for it?”

Roman, you see, has come to believe that he is invincible. You could see how he might arrive at that conclusion. The character was first introduced in 2003’s 2 Fast 2 Furious as a glowering tough guy, a sort of stand-in for Vin Diesel, who’d opted not to do the sequel.

But when Roman returned to the franchise in 2011’s Fast Five, Diesel was also back, so Roman was reconfigured as a comic-relief motormouth, a guy who’s always in over his head. Whenever the members of the Toretto crew are out on one of their impossible missions—when they’re parachuting their cars onto a remote mountain road, say—Roman is the one who always thinks he’s about to die and responds accordingly.

In F9, Roman’s dawning awareness of his own immortality becomes a running joke. Tej keeps clowning him, but Roman keeps insisting. But by the time the film reaches its climax, Roman and Tej are both wearing rubber diving costumes, driving a Pontiac Fiero through space. They do not die. Roman, one must concede, has a point.

The Fast & Furious franchise has always been comfortable with its own ridiculousness. The ongoing success of this strange piece of intellectual property is truly unprecedented. Think of it: A cheap and trashy 2001 late-summer programmer with an extended Ja Rule cameo somehow became a whole James Bondian extended blockbuster universe, one that’s dominated global box offices and made billions.

Virtually every larger film franchise has tried to capture some of that Fast & Furious magic, serving up ragtag teams of heroes who come to think of themselves as family. Nobody has captured that feeling as successfully. The cosmic energy surrounding the Fast films simply cannot be replicated.

Everyone involved seems to realize that they’ve struck gold and become a part of something bigger than themselves, and everyone involved seems to savor it. (Ludacris, only cast in 2 Fast 2 Furious because Ja Rule wanted 2 much money, definitely savors it.)

I can’t say that the series became self-aware with F9 because the series has always been self-aware in one way or another. But that whole bit about Roman realizing he’s invincible marks a new step. It’s one thing for a character to have plot armor. It’s entirely another for that character to begin to understand that he has plot armor.

Even as they’ve spiraled off into blockbuster insanity, the Fast & Furious films have always attempted to keep things physical. Whenever possible, the franchise uses real cars and real stuntmen even as they push things into pixelated overdrive.

That’s why I’ve always considered them to be action movies rather than superhero spectacles or whatever. (Genre lines are never absolute, but my one rule for action cinema is that someone has to get punched in the face, and it has to look like it hurts. The Marvel pictures rarely qualify. Fast sequels always meet that threshold.) Still, in the Fast saga, certain characters cannot die.

They’re starting to realize it. In the Fast films, death is always a mere suggestion. F9 was originally supposed to open in April of 2020. When the pandemic hit a month earlier, the producers almost immediately pushed the movie back a full year—one of the early cultural signals, at least to idiots like me, that this coronavirus thing was about to be a big deal.

Before that change in release dates, though, an F9 trailer unveiled one big plot twist: Sung Kang’s Han Lue was back, miraculously all better after being murdered via explosion in 2015’s Furious 7.

This wasn’t even Han’s first time coming back from death; the franchise had twisted itself up into logical and temporal pretzels in attempting to explain why Han was still alive after being exploded to death in 2006’s Tokyo Drift.

Once again, F9 has a long explanation for how and why Han is still alive. But once again, nobody really cares. The world wanted Han back, so Han was back. When that trailer ended with Sung Kang’s reappearance, absolutely nobody was mad about it.

Can you have an action franchise where no one ever really dies? If action cinema is defined by kinetic stakes, can the Fast & Furious movies qualify? The Fast films have always defined themselves as action cinema in ways that go far beyond just gunfights and car chases. They have cast wrestlers and martial artists and action icons: Jason Statham, Tony Jaa, Kurt Russell, Charlize Theron.

They’ve also slid in sly little allusions, too—a pair of villains called the Shaw Brothers, an extended Hard-Boiled homage where Statham gets into a gunfight while cradling an infant. But given the lack of perceived danger, maybe the Fast films are something else. Or maybe the Fast producers have just figured out more effective ways to sell action-cinema spectacle to the world. Maybe they have given us violence without danger.

F9: The Fast Saga has more than its share of beautifully inane action moments. It has a muscle car swinging on a rope like Tarzan. It has a super-magnet that makes cars crash through buildings. It has an armadillo truck flipping over mid-highway chase. It has Martyn Ford, the towering scalp-tatted muscleman who played the bad guy in the straight-to-Redbox underground-fighting classic Boyka: Undisputed, brawling with John Cena on the back of a moving truck and not even flinching when he crashes through a billboard. All of that shit is stupid, and all of it rules.

But the Fast movies have something deeper than all those setpieces, and that’s their deep bench of characters. The Fast cast isn’t exactly dominated by heavyweight actors. (Oscar winners Charlize Theron and Helen Mirren are in F9, but neither is exactly central to the storyline.) But the characters matter.

Vin Diesel, as Dom Toretto, brings a gravitas that he’s never really had in any other movies. Paul Walker had grace. Tyrese Gibson and Ludacris have chemistry. Michelle Rodriguez cuts her toughness with tenderness. The notion of family—of drag-racer superspies who love and celebrate and mourn and cherish one another—is what holds the whole ungainly enterprise together. These are essentially hangout movies with setpieces. Watch enough of them and you’ll feel like the Toretto crew are your friends.

People didn’t want Han to return to the Fast films because they wanted to see Sung Kang shooting people in the head, though it’s definitely fun to see Sung Kang shooting people in the head. We wanted to see Han’s old friends learning that he’s still alive, and F9 gives us that. (F9 even brings back a bunch of Han’s old Tokyo Drift buddies and gives them a moment with him.)

The revelation that John Cena would join the F9 cast was a big selling point—not because it meant that we got a pro-wrestling superstar to replace The Rock, who apparently can’t be in a room with Vin Diesel anymore, but because he was playing Dom Toretto’s brother.

There’s zero physical similarity between Diesel and Cena, which is fine. (Charlize Theron waves it away with an offhand line about how “the Torettos have quite the mixed bloodlines.”) It makes no sense that Dom would have a brother who he never mentioned in any of the previous eight movies or that the brother would turn out to be a hulking superspy, but that’s fine, too.

When Cena first appears, you know that he and Diesel will get into some crazy fights. That pays off; Diesel spearing Cena off of a zipline and through a window is good shit. We also know that Diesel and Cena will eventually bond and that they’ll be fighting for the same side by the end. That also pays off.

F9: The Fast Saga doesn’t take itself seriously, but it doesn’t take itself unseriously, either. Director Justin Lin, returning to the franchise after going off to make a Star Trek movie and some True Detective episodes, understands the weight of expectation.

He knows that most filmgoers won’t remember Paul Walker breaking Shea Wigham’s nose in a couple of previous films, but he also knows that those who do remember will be happy to see Wigham returning with a jacked-up nose. And he also knows that he can explore the Toretto brothers’ past in deep flashback, using long-established backstory to return to the aesthetic of the first film.

In 2021, it took a whole lot to get anyone to go to the movies. The pandemic continues to sputter to an uncertain ending, and some of us still have a hard time with the idea of breathing recycled air with strangers for hours at a time.

The films that did succeed at the box office were the ones that offered reliable, familiar pleasures. It’s a little depressing to see those pleasures, rather than the shock of the new, moving even further to the forefront of the moviegoing experience. But not all of these franchise installments are created equal, and not everybody knows how to give the people what they want. F9 understood the assignment.

Other notable 2021 action movies: With the proliferation of CGI and expert stunt teams, it’s getting a little bit less surprising when mainstream films, movies that might not even fit into the “action” bucket, have crazy fight scenes. As a result, the crazy fight scenes are starting to seem less crazy.

The bus fight in Shang-Chi is great, for instance, but it’s not surprising. The Grand Guignol throwdown in Malignant is surprising, but that’s definitely not an action movie. Still, even with all the movie stars doing wild stunt work, it was truly impressive to see Bob Odenkirk get his John Wick on in the morally layered two-fisted tale Nobody. Odenkirk, a man in late middle age with a hangdog mein and an everyman bearing, stepped the fuck up for that one. In Nobody, everything looks like it hurts. And speaking of bus fights!

There were some other treasures out there, too. Kate, Netflix’s John Wick-esque stylized tragic-hitwoman opera, gave Mary Elizabeth Winstead some beautifully severe fight scenes. (People were mad at a movie where a heroic white lady kills a bunch of Japanese people, which makes sense, but the craft of the thing still swept me away.)

Prisoners Of The Ghostland, Nicolas Cage’s post-apocalyptic samurai Western with mad Japanese director Sion Sono, is batshit fun. The Harder They Fall is deeply stylized, but its Old West shoot-’em-ups are beautifully executed. I really liked Paper Tigers, a small indie action-comedy about three middle-aged schlubs trying to avenge their late teacher.

Mostly, though, pandemic viewing habits had a weird flattening effect on action movies. These big productions that should’ve been spectacles came off instead as half-decent ways to spend another dreary evening in.

Army Of The Dead, Without Remorse, The Tomorrow War, Those Who Wish Me Dead, Boss Level—they’re all fine. Some of them are pretty good, even, But none of them have stuck with me. Maybe it’s the pandemic, or maybe the movies just weren’t memorable enough.

The films that did stick with me were, by and large, strange morality plays from other countries. Below Zero, from Spain, is a nasty little single-location escape thriller with sympathies that keep shifting. Riders Of Justice, from Denmark, is a sort of bleak revenge comedy with a truly powerful central performance from Mads Mikkelsen.

The Swordsman, a 2020 South Korean joint that came to American VOD this year, is the best blind-assassin story I’ve seen in a long minute. Wrath Of Man isn’t a foreign film, though the reunion of Guy Ritchie and Jason Statham feels pretty British even when the whole thing takes place in LA.

As I write this, there are plenty of 2020 action movies I haven’t gotten around to yet. Benny Chan’s Raging Fire is supposed to be some good old-fashioned Hong Kong violence. Copshop looks like Joe Carnahan’s take on the Assault On Precinct 13-style siege story.

One Shot, a Scott Adkins VOD joint that’s structured as a single continuous camera shot, just started streaming on the day I wrote this column. I’m looking forward to all of them, just like I’m looking forward to the moment where leaving my house to see a movie like Copshop won’t seem like such a big deal.