Last week’s episode was such a climactic moment for the series, so intense and elegantly delivered, that a return to Better Call Saul’s normal high quality is bound to seem like a bit of a letdown. But let’s pause for a second to appreciate how “Chicanery” delivered on the promise of this show. Remember when we all couldn’t quite imagine what a Breaking Bad prequel could be, and were a little afraid that filling in a bunch of backstory and providing origin stories for all the various characters would feel perfunctory, like paint-by-numbers? The introduction of new characters, like Chuck, and the rich detailing of their inner lives, has quelled those anxieties. In lesser hands, Chuck would be a foil—reflective and thin—to motivate Jimmy. He’s so much more, thanks to writers who revel in his dramatic possibilities, and to Michael McKean’s truly astounding portrayal. (How can such a likable actor play so many nuances of hateful?) We were glued to the screen last week not just to find out how Jimmy would slip his noose, but to watch Chuck unravel.

This week we might have swung the pendulum a bit too far in the other direction. The commercial laundry where Gus will build his supervillain lab, Lydia Rodarte-Quayle (intoning one line: “Okay then”), and the public debut of Saul Goodman, all in one hour. That’s more fan service than we’ve gotten on this show in a long time, maybe ever. And the dump feels more like ticking boxes than we’re used to from Better Call Saul. It’s especially jarring given that Huell’s introduction last week barely rippled the surface of “Chicanery”—a perfect entry. The trick in a prequel series like this is to drop in the elements that lead us toward the predetermined outcome without pulling us out of our investment in the new stories and characters, the ones this series is about. Admittedly, that’s a high degree of difficulty. You’re going to splash some of those dives.

Those moments distract briefly from a gorgeous meditation on family, delivered by writer Ann Cherkis and director Keith Gordon as they move back and forth between Nacho and Chuck. Michael Mando is back front and center, commanding the screen as he sits in front of Hector to receive payments from the Salamanca crews, then deferring to his father as he works late nights sewing upholstery. The latter shots are especially gorgeous, all lamplight and satisfying machinery and framing through doorways. More subtle is the contribution of camera placement to the scenes in El Michoacáno, the restaurant where Hector receives the weekly take from his street crews. Just below Nacho’s eyeline, off to his left so we can always see Hector reading the sports section of a Spanish-language newspaper behind him, this framing shows Nacho’s intimidating power, but it also catches him in between Hector and the hapless lackeys that Hector uses then discards.

By the end of the episode, Nacho has been given a dreadful choice: loyalty to his father (“a simply man, not in the business,” he pleads to Hector) or to his familia del crimen. Hector only wants to temporarily humiliate Gus by taking half—no, 60 percent—of the drugs the Los Pollos Hermanos trucks move across the border. Long-term, he needs a new front business, and he’s got his eye on the upholstery materials pipeline from Jalisco to Albuquerque. I suspect Nacho might enlist Mike to deflect Hector’s attention from that plan, and Mike may perceive that Nacho’s interests and the Fring agenda coincide. We’re certainly inching closer to open warfare between the Salamanca and Fring branches of the cartel, and I’d prefer Nacho not find himself in between them.

Speaking of open warfare, neither Chuck nor Jimmy have any interest in taking advice on their family feud. Jimmy considers the matter closed; he’s completely focused on putting his clients in cold storage so they’ll be around in 12 months when he comes off suspension. When Rebecca appeals to him for help, he responds that Chuck isn’t his brother anymore. (And besides, that’s what he flew Rebecca in for, to bandage Chuck’s wounds after the physical and psychological torment he planned for the hearing. That, and to twist the knife further by having Rebecca watch Chuck’s humiliation.)

Howard also wants to move on and put Chuck’s conflict with Jimmy in the past. “Think of the injustices that would have gone unanswered” if Clarence Darrow had put his energy into supervising “ne’er-do-well relatives” instead of the law, he pleads. Chuck seems to agree—“to new beginnings,” he toasts with Howard’s 1966 Macallan—but the fresh start he’s thinking of is retaking the offensive against his brother. To that end, he works on acclimating himself to electromagnetism by holding the batteries from the tape recorder (another gorgeous shot, with the Rayovac C-cell rolling into closeup on the table before he grabs it). He’s got a plan, and it involves Dr. Laura Cruz (Clea DuVall), the doctor whose clandestine test in the hospital conclusively demonstrated the psychosomatic nature of Chuck’s condition. Venturing out in a space blanket hoodie to call her from a phone booth, he flinches from every neon sign as the camera filter extends the lights into vertical streaks and the sound design surrounds him with crackles and buzzes.

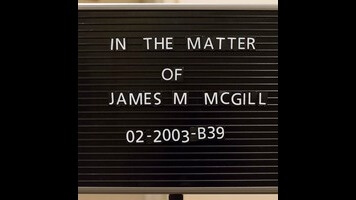

Jimmy has already turned his attention to his new family: Kim and the law practice. Unwilling to let its newest member (Francesca) slip away, frustrated that $4,000 is about to go to waste in television time he’s bought but can’t use to advertise legal services, he gathers his college student film crew and pitches local businesses on making quickie commercials that will go on the air right away. (In two hours and 45 minutes, in the case of Raby Carpet and Tile.) When nobody bites, he decides to make a commercial to advertise his commercial-making venture, in hopes of attracting enough clients for the remaining time ad slots to break even. But he doesn’t want to dilute the brand of “Gimme Jimmy!” by associating himself with another business. Solution: A Panavision hat swiped from the cameraman, a fake mustache from makeup, aviator glasses and a vest, more star wipes than the guy at the station has ever seen in a row, and a name from his past: Saul Goodman.

The ads are a short-term fix. His suspension lasts a year, and he wants to keep the office space and pay his 50 percent to Kim. Where’s the money going to come from? Not from practicing law—at least, not under the name Jimmy McGill. But he’s the only lawyer Mike and Nacho know, and they might need one soon. If you’ve been waiting for the pieces to start falling into place, look out below. Here they come.

Stray observations:

- Hector drops a pill during his apoplectic attack brought on by the news that Tuco has been thrown into solitary for a knife fight in prison, and Nacho carefully hides and retrieves it. Hmmmm.

- I am so glad Jimmy got his pretext goldfish a big tank and a bubbler, just like the underworld-connection vet advised.

- Jimmy drinks champagne from a Davis & Main coffee cup as he coolly rebuffs his former sister-in-law: “I don’t owe him squat.”

- Poor Krazy-8. He’s so clean-cut, showing up at El Michoacáno in his work polo and Tampico Furniture nametag, desperately making small talk to avoid the beat-down. Almost pulls it off, too.

- We get only one glimpse of Mike’s storyline here, and it reinforces the theme of family. But it also suggests that Mike might be mixing and pouring some concrete soon. My alarm at that prospect may spring from one of Adrian Chase’s recent supervillian ploys on Arrow, but I’m probably not the only one whose mind went straight to body disposal. What do we make of the fact that Mike doesn’t seem to remember this whole building-a-garage story that Matt told Stacey, though?

- That montage of Jimmy’s phone calls to his elder law clients is straight-up delightful, and no doubt a showcase for some of Odenkirk’s improv. My favorite: The grimace after “How did he pass?”

- That gold-backlit glass brick wall where Kim and Jimmy smoke when they work late reminds me of the roof in Homicide: Life On The Street. The creative team used to set conversations in that location to signal that the characters are about to speak the truth to each other.

- For businesses that balk at the all-inclusive commercial deal, Jimmy offers a toe-in-the-water package. Kinda scary how he can calculate a markup on a one-time rate right there on the fly.

- The number in the commercial, 505-842-5662, is the same one that appeared on the billboard in season one, episode four. Now the voicemail message is Francesca advising callers to spell out their name and wishing us a spectacular day.

- “Don’t wear stripes, you’ll moiré.”