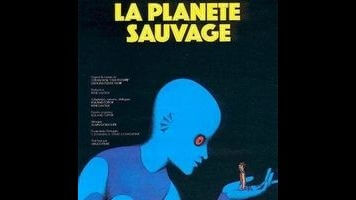

Fantastic Planet looks as strange today as it must have 40 years ago

Originally released in 1973, René Laloux’s animated sci-fi parable Fantastic Planet still looks strikingly alien, over four decades later. Its visual ideas are so outré that few have been borrowed or referenced by subsequent films, and Laloux himself made only two other features (most notably 1988’s Gandahar, which was released in the U.S. as Light Years). Not that Laloux’s imagination was the prime mover, in any case—most of Fantastic Planet’s fantastic design work came from the mind of Roland Topor, a French illustrator who’d teamed with Alejandro Jodorowsky to create a new surrealist movement in the ’60s. (Topor also wrote the source novel for Roman Polanski’s The Tenant and played Renfield in Werner Herzog’s Nosferatu The Vampyre. He was quite the interesting guy.) The nonhuman creatures are still humanoid, in order to make the intended allegory clear, but this world’s other details are so mesmerizingly weird that Criterion, which is releasing the film next week, probably wishes it could sell a pouch of primo weed with each DVD.

The film does appear ordinary for a few seconds, opening with a normal-looking woman running in terror from an unseen threat, clutching her baby to her chest. When she attempts to climb a hill, however, giant fingers repeatedly flick her back onto the ground. These digits belong to gigantic, blue-skinned, red-eyed, fin-eared beings called Draags, who are the dominant life form on the planet Ygam; humans—they’re called Oms here, a play on “homme,” the French word for “man”—are kept by the Draags as pets, though there are also “feral” colonies here and there. After the woman is accidentally killed, her baby is adopted by Tiwa (voice of Jennifer Drake), a Draag child who’s still in school, though “school” on Ygam involves wearing a headset that permanently implants factoids into the user’s brain. Through years of osmosis during these lessons, the orphaned Om, whom Tiwa names Terr (voice of Eric Baugin), learns the same information, eventually stealing the headset and bringing it to one of the feral Om colonies. Just in time, too, because the Draags are about to commence “de-Omization,” by which they mean extermination.

The Traag-Om dynamic is broad enough to be multipurpose, reflecting both racism and animal rights via “How would you like it?” role reversal. Fantastic Planet isn’t primarily remembered for its trenchant sociopolitical commentary, however. It’s Topor’s flights of fancy that linger in the memory, and many of them have little or nothing to do with the film’s skeletal narrative. (It runs only an hour and 12 minutes.) Traags eat by inhaling from a tall vertical array of unidentified foodstuff. Oms fight by strapping creatures with huge beaks to their chests and letting them duke it out. A landscape consists of looped coils that randomly rise up in spots. These oddities are all rendered in a more elegant (but still low-budget) version of the cutout animation style that had been made particularly famous by Terry Gilliam on Monty Python’s Flying Circus (which was still on the air at the time, on hiatus between seasons three and four). Along with Alain Goraguer’s prog-rock-ish score, that should make Fantastic Planet seem extremely dated, yet it’s ultimately too singular to feel beholden to a particular era. It truly earns the adjective in its title.