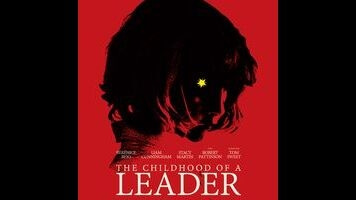

Most of The Childhood Of A Leader is set in the aftermath of World War I at a dilapidated French manor house, shrouded in greenish medieval fog. Taking inspiration from the Jean-Paul Sartre story of the same title, Corbet—a young actor who’s made a career playing “the American guy” for celebrated European filmmakers—offers up a parable about the rise of fascism, imagined as a problem child ignored by coldly high-minded parents. Brought across the Atlantic by his dad (Liam Cunningham), an American diplomat who has come for the peace negotiations in Paris, little golden-haired Prescott (newcomer Tom Sweet) throws fits, lashing out at his mom (Bérénice Bejo), their servants, and at other children with little explanation.

Here, both Europe and fascism come in quotation marks; the movie is a pastiche of allegories and Freudian dramas. The more cynical might call it Jason Friedberg And Aaron Seltzer’s Euro Art Movie: decrepit drawing rooms straight out of Aleksandr Sokurov’s studies of corrupting power, rustic misty landscapes, gloomy bilingual actors who seem to have pulled their accents at random from a bag, a small role for a cast-against-type Robert Pattinson. (Corbet, bless his heart, even includes a bibliography in the end credits.) Every now and then, one of the servants winds up the tinny Victrola or a motorcar pulls into the muddy courtyard, but for the most part, the manor house seems stuck in a purgatorial art-film whenever of governesses, peasants, and pénitents noirs who shuffle ominously through the countryside in their pointed black hoods.

But there’s a reason budding filmmakers are told to steal from the best. Studious in its homages to somber masters past and present, The Childhood Of A Leader pulls out intriguing moments—sometimes as simple as executing a creepy 1970s-style zoom or just letting Walker’s score carry a scene—whenever it threatens to turn repetitious. Broken up into acts (“The First Tantrum,” “The Second Tantrum,” etc.) with a prologue and epilogue, Corbet and co-writer Mona Fastvold’s script is schematic, but moves unpredictably, disrupted in arresting ways by a readiness to try or imitate this or that. And in that final section, having exhausted its deep well of influences, it arrives at an identity of its own.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.