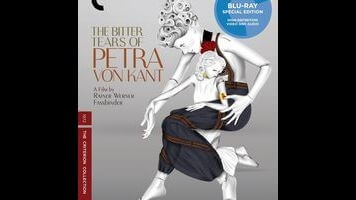

Fassbinder transforms his own stage play, The Bitter Tears Of Petra Von Kant

If one includes works made for German television, The Bitter Tears Of Petra Von Kant was Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s 13th feature… which is damn remarkable, given that he’d only gotten started three years earlier, in 1969, and was still busily working in theater at the time. Indeed, Petra Von Kant is adapted from Fassbinder’s stage production, which had premiered the year before; like the play, the movie is set entirely in its protagonist’s apartment, mostly within a few feet of her bed. Nonetheless, this is arguably Fassbinder’s first film to take full advantage of cinema’s unique qualities—so much so, in fact, that it’s sometimes difficult to imagine how it could have worked onstage. It functions reasonably well as a straightforward, agonized melodrama, but it’s first and foremost a master class—co-taught by famed cinematographer Michael Ballhaus (Goodfellas, The Fabulous Baker Boys, Quiz Show), who got his start with Fassbinder—in the dynamic visual use of a constricted space, and proof that a tiny budget is no excuse.

The story is absurdly simple: Girl gets girl; girl loses girl; girl loses mind. Petra Von Kant (Margit Carstensen) ostensibly works as a famous fashion designer, though she never seems to do anything—her entire business appears to be run by her silent servant, Marlene (Irm Hermann). On-screen, at least, Petra lounges around in bed, wearing equally garish dresses and wigs, entertaining guests. Early on, her cousin (Katrin Schaake) stops by for a chat, and is joined toward the end of the visit by a new friend, Karin (Hanna Schygulla), who’s just moved back to Germany after several years abroad. Petra invites Karin over the following evening and swiftly seduces her, whereupon the film leaps forward about six months to show that Karin, now working as a runway model (thanks to Petra), is already bored out of her mind. Petra alternately abuses and pleads with her, especially after Karin’s husband calls to reveal that he’s back in Europe. Meanwhile, all of this emotional sadism and masochism is witnessed by Marlene, who clearly carries a torch for her employer but stoically behaves like a worthless underling at all times.

Initially, Marlene seems to be Petra Von Kant’s most contrived aspect, as the script’s general naturalism deliberately clashes with her chalk-white face and her speechlessness. (She apparently can talk, as she answers the phone at one point; Petra grabs the receiver before she can say anything.) There are some outré touches in the set design—like the huge reproduction of Nicolas Poussin’s Midas And Bacchus adorning one entire wall—and the film becomes more and more surreal as it progresses, until Marlene begins to seem like a natural outgrowth of an unnatural environment. After Karin leaves Petra, for example, there’s another slight jump forward in time, and suddenly the bed that’s dominated the movie is gone, without explanation, leaving the heartbroken Petra to mourn her lost love from the floor. Only some time later do we see that the bed has been moved to another section of the apartment, and that two dressmakers’ mannequins have been placed under the covers, one atop the other, as if making love. (This is never commented upon by anybody, or even highlighted. It’s just a disturbing background detail.)

As a play, The Bitter Tears Of Petra Von Kant probably had a stronger second act that compensated for the considerable longueurs of its first act. Even on-screen, the opening hour must have involved a great deal of rather turgid dialogue in which characters describe things that happened in their pasts: Petra explains to her cousin in great detail why her second marriage failed; Karin tells Petra the story of her tragic childhood; etc. A brilliant playwright Fassbinder was not. But he and Ballhaus shoot this material with such creativity and precision that it’s nearly impossible to pay attention to what anyone’s saying anyway. There’s nothing especially flashy going on—it’s just that every composition and camera movement is perfectly judged, every cut to another angle revelatory. (One abrupt change of vantage point, at a key moment, creates the impression of an entirely different room.) Mirrors are craftily employed at times, yet the geography, both physical and emotional, is always coherent. Ironically, the one shot that does seem stagebound, designed with a proscenium in mind, is the final shot, which depicts actions that—according to the essay by Peter Matthews included with the Criterion release—didn’t take place in the stage version, which ends a few minutes earlier and much more happily, at least for Petra. Combined with the appearance of a gun that cheekily inverts Chekhov’s famous theatrical maxim, this revised ending demonstrates the self-awareness of a great filmmaker who was finally ready to leave the theater behind.

The Bitter Tears Of Petra Von Kant is available on DVD and Blu-ray from Criterion. It can also be streamed on Hulu Plus.