Feel Good tells a specific, intimate story about trauma in ambitious season 2

Created by and starring comedian Mae Martin, Feel Good accomplished so much in its first season, offering a layered and dynamic exploration of gender, sexuality, addiction, relationships, and self-discovery. Its second season, also just six episodes, is just as richly textured and even more ambitious in its storytelling. Martin’s comedic voice is original and sharp, and the show unflinchingly embraces discomfort and mess.

Many of the central themes from season one continue here: a surprisingly thin line between self-fulfillment and self-destruction, the highs and lows of relationships, the tension between one’s self and how one is perceived by others. Mae’s addiction is still a significant part of her arc here—in the span of the premiere, she both checks into and out of rehab—but season two also introduces a new set of obstacles that builds on some of the character work last season. Reconnecting with her parents made Mae confront her past, and as she realizes that her memories of her teenage years are fragmented and sometimes lost completely, she begins to process things that have laid dormant, making her feel, in her own words, like her brain is a cupboard full of empty Tupperware rattling around.

The specificity of that metaphor speaks to Feel Good’s complex and honest portrayal of its protagonist. It’s funny and disturbing all at once, but also very centered on Mae. She describes how she feels in her own words, and the image is indelible. A reunion with an old close friend morphs from something celebratory into something much darker. Feel Good asks very difficult questions about trauma, memory, and survival, which it handles with astonishing depth and empathy.

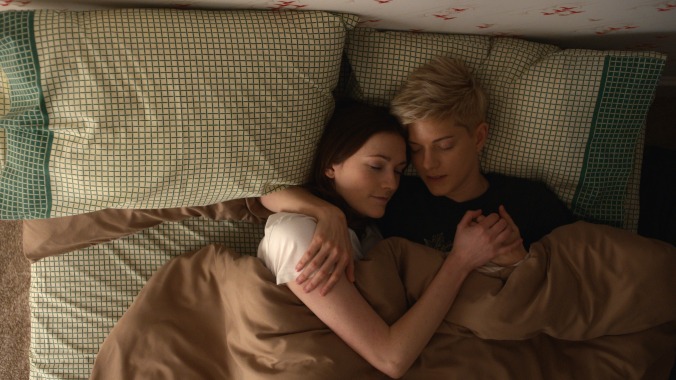

As Mae is reconciling with her past, she’s also exploring a renewed relationship with George. It’s still a rollercoaster of emotions, with genuinely romantic moments, but also a lot of pain and confusion. Martin and Charlotte Ritchie are a comedic dream team, suffusing the comedy with real emotional stakes and equally strong dramatic acting. Many of the scenes and comedic setups throughout the season do several things at once. An increasingly elaborate series of sexual role play situations George and Mae act out is, yes, very funny. But the montage operates on several levels other than just humor. Mae and George are quite literally turning their relationship into an escape. They’re not really getting to know each other, more focused on devising role play than building a life together. George isn’t in the closet anymore, but a lot of her same issues—codependency and emotional avoidance, namely—persist unchecked. When George reconnects with former friends, one points out George and Mae don’t know the meaning of intimacy. Shortly after, the fun fantasy of their sexual escapes is bleakly punctured by reality, by literal shit and blood, and the role playing suddenly look so different in retrospect.

Feel Good’s sex scenes continue to be distinctly queer in a way that doesn’t feel catered toward heteronormative assumptions. These scenes play with a range of power dynamics and toys and are closely connected to the characters’ arcs, operating similarly to a lot of the jokes in the series in the sense that there are stakes and latent meaning just beneath the surface that gradually get teased out. George and Mae are arguably at their most functional and communicative while they’re having sex. The role play means more than just sexy fun to Mae—she has other reasons for wanting to pretend to be someone else.

George also experiences several crises of the self, newly liberated by being out of the closet but also faced with a whole new set of questions about what she really wants. A new character lectures her on having a more feminist approach to her own sexual desires, which hilariously and ironically serves as an indictment of her sexual agency. But beyond the bedroom, George also grapples with identity, frustrated by her lack of passion and facing several roadblocks on the way toward claiming her independence. She values Mae’s problems over her own.

Feel Good’s depiction of relationship conflict and drama often feels more nebulous—in a good way—than TV usually allows for. The relationships in the series, like the characters, are deeply flawed, sometimes unlikeable. Phil (Phil Burgers), who continues to be a very fun take on the quirky sitcom roommate trope, tells Mae and George that they’re kind of a difficult couple to be around. George and Mae often become myopic as individuals and as a unit. Characters throughout the season act selfishly, regress to bad patterns. The true nature of a grand romantic gesture is exposed as manipulative and self-serving. Feel Good delights in subverting expectations and complicating not only its characters, but its story devices, too.

The season also includes funny but sharp meta references to TV depictions of trauma. “Trauma is incredibly trendy right now,” Mae says, quoting her agent. Feel Good flies in the face of that sentiment, telling a story about trauma that doesn’t feel exploitative or gratuitous but rather presents its characters as imperfect, multidimensional humans who are not defined by trauma. The show eschews fixed categories of good or bad. It’s more concerned with mess and with story arcs that are more labyrinthine. Trauma, healing, and identity are not straightforward paths at all. Mae’s relationship with her gender is similarly circuitous. George and Mae’s tumultuous relationship is a maze. The narratives throughout this season refuse to be neatly packaged.

This isn’t a “feel-good” story, and it’s not an altogether cynical one either. These characters experience growth, catharsis, and small victories. Friendships and relationships are rebuilt. None of it is easy. Feel Good recognizes that all relationships require real work—including one’s relationship with one’s self. Throughout all these messy character and relationship arcs, there’s still that goofy and original comedic voice established in the first season that sometimes verges on the absurd. Life is, after all, absurd. And Feel Good does a brilliant job exploring that.