Fellow Travelers review: An epic gay love story that's as heart-wrenching as it is heartwarming

Matt Bomer and Jonathan Bailey star in Showtime's decades-spanning romance

Is it better to have loved and lost than never to have loved at all? That is one of the questions at the heart of Fellow Travelers, the intoxicating Showtime/Paramount+ limited series about two men who fall in love at the height of McCarthyism in 1950s Washington D.C. and weave in and out of each other’s lives for years at a time before coming to terms with their whirlwind secret romance during the AIDS epidemic of the ’80s. Equal parts historical drama and political thriller, this eight-part series is the first of its kind, telling an epic gay love story across four decades that is as heart-wrenching as it is heartwarming.

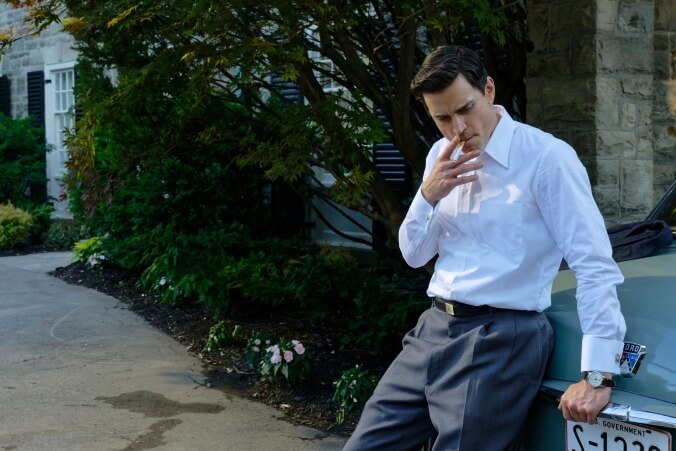

Based on the novel by Thomas Mallon and created for television by Ron Nyswaner (Ray Donovan, Homeland), the beautifully shot and thematically rich miniseries, which premieres October 27, chronicles the tender, volatile, and deeply passionate relationship between Hawkins “Hawk” Fuller (Matt Bomer), a charming and debonair war hero turned political staffer who is able to compartmentalize his life, and Timothy “Tim” Laughlin (Jonathan Bailey), an idealistic young Fordham University graduate who is optimistic about the future and earnest about his political and religious convictions.

After meeting on the night of President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s victory in 1952, Hawk and Tim begin seeing each other late at night just as Joseph McCarthy (Chris Bauer) and Roy Cohn (Will Brill), determined to weed out any so-called “communists” and queer people working in the U.S. government, declare war on “subversives and sexual deviants” and incite a kind of moral panic about homosexuality (despite rumors that McCarthy and Cohn are gay themselves). Although their paths eventually diverge, Hawk and Tim continue to cross paths over the years, unable to resist the pleasure of each other’s company. It’s their relationship that anchors the sweeping story across decades—through the Lavender Scare of the ’50s, the Vietnam War protests of the ’60s, the drug-fueled hedonism of the ’70s, and the public-health crisis that disproportionately affected gay men of the ’80s—and that allows Bomer and Bailey, who are extremely well matched, to deliver the best performances of their respective careers.

Hawkins Fuller is a man of many contradictions, continuing to lead a kind of double life into his fifties and sixties. For the early years of his adult life, the war veteran, who has a very specific ethos as a gay man, was able to avoid emotional entanglements with women while secretly prowling for other men in both public and private spaces in pursuit of a kind of sexual dominance that is immediately evident in the pilot. But as he becomes further enmeshed with Tim, Hawk’s façade—with his ability to code-switch, to lie not only to himself but to those around him, and to mask his sexuality with presentations of hyper-masculinity—begins to show signs of corrosive wear and tear as he grows older.

Before long, Hawk is forced to confront whether he is truly in love with Tim or simply enamored with the power he has over him. (And that power, despite some noticeable shifts in sex scenes, remains pretty consistent throughout the story.) With his chiseled good looks, Bomer fully commits himself to embodying the fascinating dichotomy of his character—both a doting husband and father of two, and an older man attracted to younger men—and imbues Hawk with a magnetism that makes it difficult not to root for him to reach a place of self-acceptance, even when he makes misguided decisions of self-preservation that threaten to upend not only his life but those of his loved ones.

Tim, meanwhile, is forced to reconcile his deeply religious upbringing with his undying love for Hawk. (At one point, he reluctantly confesses to a priest, “I don’t know how love can be a sin.”) Bailey, in a dramatic departure from his portrayal of the oldest brother on Bridgerton, is able to play a different kind of romantic lead in Fellow Travelers—someone who is more inexperienced, albeit just as consumed and infatuated with a prospective partner he knows he probably can’t have. But Bailey and the writers are careful not to portray Tim as a victim or someone in need of a consolation prize, giving him an opportunity to grow personally and professionally outside of his relationship with Hawk to the point that, as time goes on, he eventually becomes more of a mentor than a mentee to the one true love of his life.

Since Bailey’s casting was announced last year, there has already been a lot of social-media chatter in anticipation of the sex scenes in Fellow Travelers—and that discourse has only intensified with the release of the first intimate scenes. In one scene, for instance, Tim uses sex to get an invite to a party, asking Hawk, “I’m your boy, right?” Bomer, Bailey, and the creative team have managed to find different expressions of Hawk and Tim’s love and intimacy over different time periods, with no sex scene ever being the same.

Those explosive scenes shift the power dynamics of the relationship back and forth and push the boundaries even on a network like Showtime, which famously aired Queer As Folk in the early aughts. While Tim learns a lot from Hawk about power and dominance, Tim, on a more profound level, also opens Hawk up to the dangerous possibility of falling in love with another man again. One could even argue that this story could have conceivably been told in only a single era—in the ’50s, like Mallon’s original novel—but the decision to tell a more ambitious story in scope allows the audience to relive key events in queer American history and watch these characters grow and evolve over time, even if the execution wanes in the later decades.

For his adaptation, Nyswaner also decided to expand the scope of representation with the addition of a decades-long relationship between Marcus Hooks (Jelani Alladin), a promising journalist struggling to embrace the intersections of his identity, and Frankie Hines (Noah J. Ricketts), a drag queen turned activist, to parallel that of Hawk and Tim. Alladin and Ricketts are both a revelation, each playing their part to deliver an unexpectedly poignant queer Black love story that both complements Hawk and Tim’s romance and can easily stand on its own. But since much of the season was built around Hawk and Tim, one could argue that the writers could have gone even deeper into Marcus and Frankie’s relationship, especially later in the timeline. A potentially interesting lesbian storyline was also quickly discarded after a couple of episodes, but that remains something that could potentially be explored in future seasons. (Nyswaner and producer Robbie Rogers have reportedly expressed an interest in “turning the miniseries into an anthology series that would track different queer fellow travelers across history.”)

Allison Williams, who plays Lucy Smith, the daughter of the senator Hawk works for during the ’50s, does the best she can to elevate the limited material she is given. After all, playing the unsatisfied wife who intentionally chose to overlook her husband’s extramarital activities for the sake of their children can only go so far in a love story about two gay men, but the tension in her relationship with Hawk really comes from the brief moments when she and Tim are at risk of intersecting in the story.

In fact, so much of the tension early in Hawk and Tim’s relationship lies in the fact that they are working for ideologically different politicians in the same building, which explains why the first half of the series is especially compelling. But once they are no longer in the same line of work, that tension becomes more and more difficult to sustain in the middle section. It comes as no surprise, then, that some of the years after Hawk and Tim’s lives have gone on completely different trajectories—specifically, during the ’60s—are the story’s weakest. (At one point in that decade, Bailey dons an absolutely atrocious wig, but that’s neither here nor there.)

Viewers, due to the way the show has been set up as a miniseries, inevitably only get small windows into Hawk and Tim’s relationship after the ’50s until the characters reunite in the Bay Area in the ’80s. And while these vignettes in the interim help plant necessary seeds that come to fruition in the final episodes, those brief glimpses, with the exception of some unexpectedly funny scenes between Tim and one of Hawk’s children, struggle to sustain the momentum of the earlier years. One of the potential downsides to telling such an expansive story—especially one that jumps between multiple decades in one episode—is that Fellow Travelers requires more expository dialogue than most shows to help us fill in the gaps and understand why the characters’ behaviors are suddenly so different from who they were a decade or two ago. Interestingly, the limited series works best in the ’50s and the ’80s, when the writers decide to strip away any unnecessary minor characters and, instead, keep the focus on Hawk and Tim’s inextricable connection. But all in all, this is the kind of devastating love story for the ages, brought to life with the undeniable talents of Bomer and Bailey, that will stay with you long after the end credits roll.

Fellow Travelers premieres October 27 on Showtime/Paramount+