Screenwriting manuals and workshops frequently suggest three key questions to be asked when crafting a story: 1) What does the protagonist want? 2) What’s in the protagonist’s way? 3) What happens if the protagonist doesn’t get it? Generally speaking, that third question is hypothetical—it represents the threat, which will only be realized at the end of the movie, if it’s realized at all. What’s remarkable about Félicité, an offbeat character study made by the Franco-Senegalese director Alain Gomis, is that it devotes its entire second half to exploring what happens when the title character fails to achieve her goal. It’s as if Seven’s bleak conclusion had been that film’s midpoint and Morgan Freeman’s detective, rather than muttering “I’ll be around,” had proceeded to have a complete nervous breakdown. Indeed, Félicité itself seems to lose its bearings, in the best possible way, once its ostensible plot has collapsed.

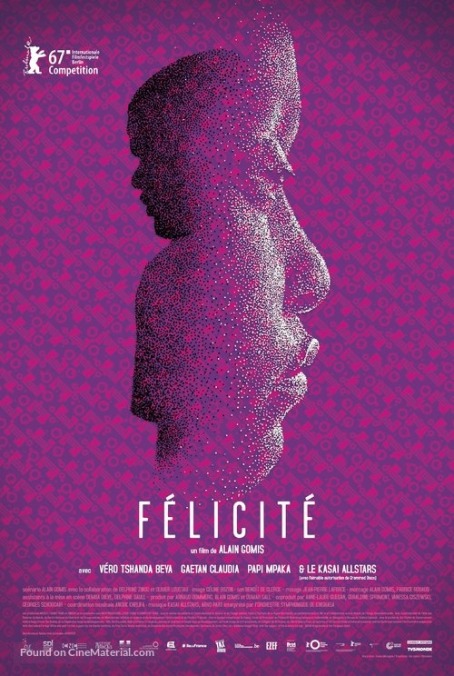

Gomis sets up the bait-and-switch with casual expertise. (This is his fourth theatrical feature, but the first to receive U.S. distribution; it probably helped that it won the Silver Bear, second prize, at this year’s Berlin Film Festival.) Set in Kinshasa, Congo, Félicité introduces the title character, played by superb newcomer Véro Tshanda Beya, at her job, singing for the rowdy, drunken patrons of a local bar/eatery. She commands the crowd effortlessly (accompanied by real-life ensemble the Kasai Allstars), but Félicité’s personal life, as a desperately poor single mom, isn’t nearly so smooth—especially once her teenage son, Samo (Gaetan Claudia), gets badly injured in a motorbike accident. If you think our healthcare system is a nightmare, be glad you’re not in the Democratic Republic Of Congo, where patients who can’t afford crucial operations apparently just don’t receive them. Frantic to save Samo’s leg from being amputated, Félicité has no choice but to beg total strangers for the necessary funds, even as she continues to perform for tips at the bar every night, barely masking her suffering with professional exuberance.

For about an hour, Gomis works in the mode of the intensely naturalistic urgency perfected by the Dardenne brothers, with Félicité echoing the singleminded heroines of Rosetta and Two Days, One Night. When it comes to her son’s well-being, she will not take no for an answer; it’s painful to watch her literally get dragged kicking and screaming across a wealthy man’s floor after he refuses to help. About halfway through the movie, though, Félicité’s quest comes to an abrupt end. What follows, for about another hour, is anything but familiar, as Félicité turns near catatonic and Félicité unexpectedly shifts into a sensual, oneiric limbo state. It becomes unclear whether certain scenes are real or imagined, and musical interludes become both more frequent and more expressionistic. In its dolor, the movie takes flight.

Somehow, this sustained rupture doesn’t undermine the first half’s commitment to stark reality, elements of which remain even as the movie goes haywire from a formal perspective. Beya’s passionately unfussy performance, both onstage and off, serves as a magnificent constant; she’s equally at home getting right up into people’s faces and silently observing the chaos at the bar as Félicité waits to take the mic. Gomis also throws in some nicely judged comic moments, most of them involving a compassionate but frequently drunk friend/suitor (Papi Mpaka) who spends much of the movie trying in vain to fix Félicité’s broken refrigerator. The film’s tonal range is formidable enough to suggest that this director may be a major talent who’s now emerging from relative obscurity, thanks to the Berlin prize and subsequent attention at festivals in Toronto and New York. It’s always exciting to discover someone who’s eager to toss the manuals aside.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.