The length of the Feud series enables us to see what life was like for these creative performers and artists as they endeavored to get from project to project. On a much smaller scale, i can relate. There will be an article I work on and slave over, and it’s highlighted on the site for a day or so, and then it disappears. Almost immediately, I need to get on to my next piece: It’s definitely like a high, and an impulse that I don’t seem to have much control over. Yes, it’s my job, but it becomes more than that: Whenever I’m not writing, no matter what else I’m doing, I always miss it.

But writers, like painters, or sculptors, have the advantage of being able to just do their work, whether or not anyone has actually hired them to do it. Actors, and directors, aren’t as fortunate. What is an actor supposed to do, read Shakespeare to themselves aloud? (Full disclosure: part of this concept comes from a speech in Stage Door, one of my favorite movies.) So in this episode, it’s easy to understand what led Bette and Joan to take on this series of increasingly more outlandish projects, even past the financial reasons: I just think of that ache between stories. After nine months, it’s no wonder Joan leapt at Strait-Jacket. As she says in this episode, it not only keeps the lights on, but it’s part of her persona overall. She refuses to go to even goes to parties if she’s not working on a movie, because she’ll have nothing to talk about. Bob is completely lost between pictures, so much so that he’s reduced to puttering around the house in his slippers. And Bette Davis did actually work on Wagon Train (and Joan eventually found herself on television as well, where she was directed by an extremely young Steven Spielberg).

It’s also interesting to learn that Baby Jane kicked off the “Hagsploitation” genre of the episode title. That script that Catherine Zeta-Jones’ Olivia De Havilland pitched into the Parisian wastebasket was apparently dug out again: Lady In A Cage featured De Havilland as a rich and famous poet (?) who gets stuck in an elevator between floors on the way to her penthouse. There she is tormented by a bunch of young thugs, led by a young James Caan. It’s a genre movement that appears to be based merely on the tormenting of older, famous women, the degradation that Jack Warner draws out of new employee Bart, and so blithely refers to. And degradation is clearly also the theme for the other characters in this episode.

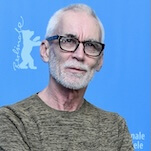

After the actual horror of filming Baby Jane, Bette and Joan both demand more from this new movie. Bob, at first having not learned his lesson about dealing with Jack Warner, is unceremoniously tossed out of his office after learning he will in fact receive a lesser salary for Baby Jane. In a way, he’s more vulnerable than the stars are: Everyone wants to see Bette and Joan back onscreen together again, but Warner could probably find someone else to direct them. Except that it’s Bob’s movie, which he shops to Warner’s enemy, Darryl Zanuck. Warner’s comeuppance is a thing of actual beauty, although I hope this doesn’t mean the end of Stanley Tucci in this series, because I love every scene he’s in.

So Bob got his balls back, but how do Bette and Joan do that? We’ve seen them see-saw their own leverage from the very first episode. Bette’s devastation from last week, we learn, will have a long and defining consequence for Joan. They may be on the picture together, but it looks like Bette is going to make this experience sheer hell for her. But this episode is all Joan’s (Sarandon doesn’t even show until 20 minutes in), as we learn of her considerable efforts to escape her meager upbringings, which included a few stag films, resulting in a blackmail effort from her own brother.

It’s amazing how Lange as Joan still manages to draw sympathy for her character; there could be no greater degradation than an ax-wielding Joan Crawford in evening wear (complete with awesome John Waters cameo). We still feel for her even as we see all of her terrible plotting, even as she throws a vase of flowers at Mamacita’s head or hisses at her brother who’s about to go into surgery. She is so committed to image above everything, even actual reality, which is why that shot of her drunken self underneath the idealized portrait in her living room may be the most striking of this episode. Joan, we know, was not in this for the work, but to be a capital s Star. She sacrificed so much to get there, but in the end she’s so isolated, alcoholic and miserable, you have to wonder what all that effort was for.

In Feud, we see the creative demons that push these people, Bob and Bette and Joan, who will do anything to get to their next project, hoping that this will be the one that brings them everything they need. But what if it doesn’t? (In Bob’s case, it actually loses him the person that he loves.) And what if, as time goes on, those projects become less and less likely to do so?

Stray observations

- So many LOL lines this episode: “You know who said that?” “The New York Times.” “ME!” Also, Hedda’s embrace of the horror of her life’s work: “And I felt… good.” Also: “You smashed all my Sinatra records. “ “Yeah, I thought it would make me feel better, but it didn’t.”

- Joan Crawford’s brother actually died in 1963, a year before this episode takes place. I’m still kind of processing this: Feud obviously is a fictionalized version of what really happened in those Hollywood years, but manipulating life events to more closely align with the preferred narrative almost seems like stepping over the line somehow?

- If that wasn’t a real promo for Strait-Jacket, it should have been.