It’s no doubt hackneyed to wish that David Carr were still around, writing us through these strange and often difficult days. How would the journalist cover our absolute failure of a president? Our nation’s steadily downward creep in goodwill? What would he write about the #MeToo movement? Would he love Succession? What would he say about social distancing?

Carr was one of the few remaining American intellectuals worth a damn, and his death, five years ago, left an abyss in the pages of The New York Times’ media and culture coverage. Carr would most certainly eschew that label: intellectual. He was a reporter through and through, an old-school newspaper man who just so happened to cover the new media beat, a writer who shoe-leathered, muckraked, and black-inked his way from Minneapolis to the Old Gray Lady’s cubicles. Carr could be provocative, acerbic, and downright savage. But he always—always—punched up.

“I’m just saying, I’m not a journalist,” Shane apologizes.

“Obviously,” Carr gruffs. “Go ahead.”

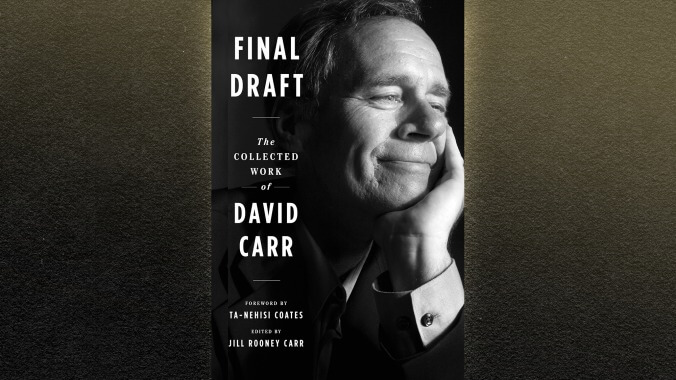

Carr published just one book in his lifetime, The Night Of The Gun (2008), a superb, noirish memoir about his drug dependency, cancer recovery, and experience single-parenting twin daughters. Now we have Final Draft, a diverse volume of collected work edited by his widow, Jill Rooney Carr.

The collection leads off with a handful of early freelance pieces he wrote for various Twin City publications. The most compelling are a pair of personal essays about the inpatient treatment center he called home in the late 1980s, including one filed directly from rehab. “No one here is telling me that ‘this time’ is the last time I’ll be in treatment,” he writes two months into his six-month stay. “But that’s okay. I sit on the edge of my skinny bed and hear the chatter of a therapeutic community in the background while I type. It isn’t exactly the highlight of my professional career, but it feels right for now.”

Alongside these memoiristic pieces, Carr’s Twin Cities period features the journalist condemning thieving politicians and humanizing the AIDS epidemic. He finds common cause with other down-and-out misfits looking for their umpteenth chance: a repentant commercial airline captain banned from flying for drinking 19 rum and Cokes the night before a flight, and the actor Tom Arnold, wrestling with sobriety and life with Roseanne.

In 1995, Carr joined the editorial staff at the Washington City Paper, where he farmed a bullpen of impressive mentees, including Jake Tapper, Jelani Cobb, and Ta-Nehisi Coates, who contributes a foreword. At the alternative Paper, Carr also wrote a media column that delighted in skewering his favorite bêtes noires: new-media upstarts like Slate and old-media elitists like Greta Van Susteren, Christopher Hitchens, and, more often than not, The Washington Post, where the opinion pages, he mocked, resembled “an elephant burial ground, a place where tired, spent ideas limp into view and keel over.” Despite juicy zingers like that one, a few of these articles fail to carry the weight they once did, unless you remain interested in media arcana such as the ins and outs of editorial staff changes at The New Republic in the late ’90s.

Carr’s articles for The New York Times, where he joined the business section in 2002, remain as relevant and readable today. His 2010 takedown of the Tribune Company’s sexist corporate culture foreshadows the #MeToo movement. He reports the bullying tactics of Bill Cosby, Fox News, and Ann Coulter. In long-form articles, he profiles fellow members of the nine lives club—albeit now celebrities with much higher profiles: Julian Assange, Neil Young, and Robert Downey Jr. “Look at him standing there,” he writes of Downey, “a great big movie star in a great big movie, the Iron Man with nary a trace of human frailty. A scant five years ago the only time you saw Robert Downey Jr. getting big play in your newspaper came when he was on a perp walk.” That lede is pure Carr— candid, chatty, punches resolutely unpulled.

David Carr died on February 12, 2015, after collapsing in the Times newsroom. Sure, it’s a shame we’ll never read his words on Trump and co., but it’s all there, in these essays: his hate for bullies and love for news media, his personal integrity, intelligence, and empathy. We should marvel at the opportunity to read him again.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.