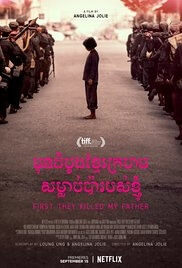

First They Killed My Father depicts genocide through a child's eyes

The most remarkable thing about First They Killed My Father is how quiet it is. Angelina Jolie’s film—about the Khmer Rouge regime that killed one quarter of the population of Cambodia between the years of 1975 and 1979—is based on a memoir by human-rights activist Loung Ung, who was 5 years old when the Khmer Rouge came to power. Jolie runs with this premise, telling the story of a people through the eyes of a little girl. As a result, the film is an impressionistic, fragmented, sometimes slow affair, one that interweaves tragic and disturbing moments with quiet and hopeful ones. And, by and large, the artistic strategy pays off.

Following an undeniably clichéd Oliver Stone-esque opening montage combining Richard Nixon, late ’60s news footage, and “Sympathy For The Devil,” we open with a brief moment of innocence as Loung Ung (newcomer Sareum Srey Moch) and her siblings dance to Cambodian rock music as their parents speak in hushed tones about the impending American invasion of Phnom Penh. And soon enough, they’re interrupted by the arrival of tanks and soldiers telling them that “Angkar” (Khmer for “the organization,” a general term for the Communist Party) is now in charge.

Thus begins the long, ultimately four-year forced march of Loung and her family across the Cambodian countryside. Initially settled in a work camp where Pa (Phoeung Kompheak) and Ma (Sveng Socheata) warn the children not to reveal their true identities—they never say why, exactly, but it’s to avoid being targeted for execution thanks to Pa’s position in the ousted royal government—the Ungs are safe, if hungry, broken, and exhausted, for a little while. Then the Khmer Rouge’s oppression begins to ramp up, from mandating that everyone dye their clothes the same shade of black to hard labor in the fields to drafting children into military units where they plant land mines and learn to fire automatic weapons. Emotion is forbidden; Ma is only allowed a few seconds of grief after being told one of her children has died.

The film is initially dispassionate as well, maintaining a sense of distance by depicting highly emotional moments in bits and pieces that highlight Loung’s childlike perspective. (Pa’s tearful farewell to his wife before being led away by Khmer Rouge soldiers is literally spied through a hole in the wall of their straw hut.) The approach keeps us in Loung’s headspace, along with dream sequences where she fantasizes about eating from a smorgasbord lit with glowing yellows and pinks and watching a once-luminous Ma put on lipstick. But as Loung’s day-to-day life grows more distressing, so does the imagery, which reaches an emotional, gory climax in a scene where Loung tries to avoid land mines she herself was forced to bury. The soundtrack, initially hushed, builds along with the story.

Jolie’s direction alternates between intimate close-ups of hands and faces and extremely wide overhead shots reducing huge crowds to human insects, further hammering home the dehumanizing agenda of the Khmer Rouge. But while her method produces the intended gasps when things go from miserable to outright nightmarish, viewers without a firm grasp of Cambodian history may reach the same half-formed understanding of events as young Loung. Casting controversy aside, no one can deny Jolie’s earnest intentions when it comes to the film. Her adopted son Maddox, who was born in Cambodia, is listed as an executive producer on the project, as is Loung Ung herself, and a dedication “to those who lost their lives under the Khmer Rouge—and those who survived” drives home a final message of hope. But First They Killed My Father works better as a mood piece—an accomplished, if overly long mood piece—than a history lesson.